A Literary Answer to Inadequate Legal Definitions of Ground and Soil

In this entry, Frans-Willem Korsten explores the need for a sensible legal definition of ground and soil. Inspired by popular culture and academic texts, Korsten advocates for literary sensibilities in the political task of creating definitions that reflect ground and soil’s living nature.

Literature and law both have the capacity to produce realities because they are techniques through which things can be made that did not exist before. Both deal, in different ways, with fiction, a term derived from the Latin fingere, meaning "to make." Law, for example, makes human subjects into legal subjects, or persons. Literature, on the other hand, has created gods and deities that were used, in turn, to underpin legal systems. Given their shared capacity to make and shape realities, literature enjoys the maximum freedom “to say all,” as Jacques Derrida put it, while law focuses on defining limits with precision for the sake of safeguarding order.

Currently, law’s limits are more and more expanded, however. For the sake of better protection entire natural environments have been turned into “legal persons”. Giving rights to things or beings may sound logical or plausible. And perhaps, by granting rights to nature, we will be able to better protect it. It will also lead to more court cases in which private parties with abundant financial means can buy the legal expertise that nature, or an appointed warden, lacks. The probable result is that nature will be getting the short end of the stick again, this time on the basis of judicial decisions. In my reading, the fact that natural environments become legal persons is the wrong solution to another problem.

Look for instance how soil (bodem) is defined in Dutch law, in Article 1 of The Soil Protection Act: “The solid part of the earth with the fluid and gasiform parts and organisms therein.” Soil as grond – ground – got its own definition because in 2002 the minister of VROM (Housing, Land Use Planning and Environment) decided a uniform definition of ground was needed because the term was defined differently in different laws. This led to consultation of so-called stakeholders in the years 2003/2004. This was the result:

The devil, as usual, is in the detail. Here, the simple phrase “such as” hides a conscious or shrewd choice. The report on the deliberations leading to the definition states: “Furthermore it has been decided to consider ‘grond’ as an ex situ concept.” Ex situ means that soil is considered apart from, or outside of, its natural habitat. If you thought that on the basis of this definition, ground can be found in the soil, you might be disappointed. The report states: “So, there is no soil in the soil.” This may explain why, juridically speaking, there is nothing alive in the soil.

The limits that law defines here by means of its definitions, facilitate the instrumental use of soil. This is why we have to research the foundation on which legal definitions rest, or their conceptual breeding ground, and why we have to look for alternatives. Were I to speak on behalf of nature, not as a warden but as a co-animal, I’d say: “Instead of giving more rights, what if you would first live up to your obligations, you murderers, butchers, polluters, abusers, thieves, exploiters, poisoners!?” The choice of words makes it clear I want to live in solidarity with animals or any living being or entity. It affectively underpins my research into, and my search for an alternative to the limiting conceptual breeding ground of the legal definition of soil.

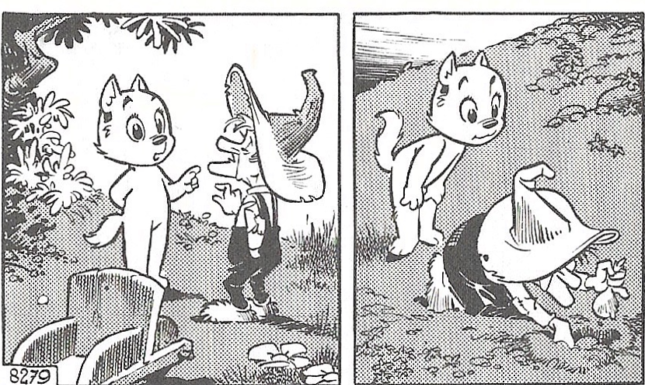

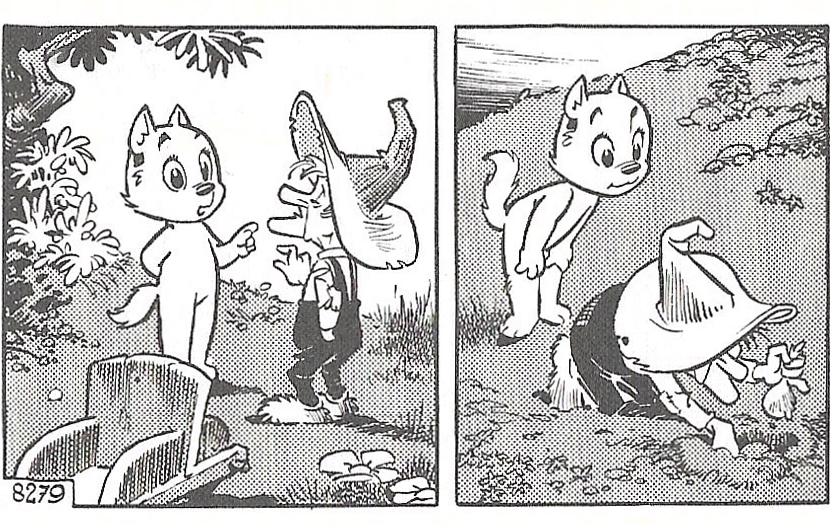

An alternative to the limiting sensibility that law facilitates, has been given by all sorts of art and literature, from low to high culture, and with more intensity since the 1970s. The basic problem dealt with was the insensitivity of humans’ dealing with their environment; an environment polluted and destroyed. Popular comics at the time dealt with this issue; one example was the Tom Poes (Tom Cat) series, made by Marten Toonder. In a volume entitled De opvoedering – a pun in Dutch on both educating and feeding – Tom is much helped by a character called Pee Pastinakel, a name that in turn is a pun on pastinaak, or parsnip: a root vegetable. It is no surprise that this character is knowledgeable about everything that grows in the soil and flowers from it.

This image shows the attentive posture of Tom Poes. Also noticeable is that Pee is clothed whereas Tom is not. In the Bommel-stories, every single character is clothed, whether animal or human. The cat without clothes stands out as a result. Time and again it appears that Tom Poes’ intelligence is not fed by modern scientific insights, nor is it common sense. It concerns an intellect that is capable of connecting itself to everything without ever appropriating it. Tom Poes’ capability is to be attentive and to listen closely. It is clearly an anthropomorphic character, but also both a cognitively and affectively perceptive animal. Socially speaking it has nothing, literally and figuratively, to pride itself on, so clothes are not necessary.

In my research into, and search for a more sensible legal definition of soil and ground, I find a source of inspiration in many texts, from low culture to high culture, and not only from within the humanities. When studying the legal definitions of soil, the pivot appeared to be that there was nothing living in soil as grond. Recent scientific research into soil has proven, however, that the soil is alive. Fungi are not so much living in the soil, but make soil, and make up the soil. There is no fertile soil, that is, without the life and work of fungi. In any sensible meaning of the term, we would have to consider soil as an organic, living entity in itself then. This in turn should lead to another attitude with regard to the soil, and by implication to a legal definition that does justice to this. Since legal definitions in the end find their source in politics, the scholarly conversation between literature and laws should not be the end-goal, then. If we are to make new realities, or a better world, the scholarly task is also to consider the political potential in literary studies, or in a form of environmental humanities that proves itself worthy of that name.

© Frans-Willem Korsten and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2024. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Frans-Willem Korsten and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Works cited:

Article 1 of the Soil Protection Act, Rijkswaterstaat, Netherlands 2013

accessible at wetten.nl - Regeling - Wet bodembescherming - BWBR0003994

“Voorts is besloten het begrip ‘grond’ op te vatten als een ex situ begrip.” Naar een uniforme definitie van “grond” in de bodem- en afvalstoffenregeling. 2004, 6.

De opvoedering appears in the collection:

Ik Voel Dat Heel Fijn Aan - Marten Toonder, De Bezige Bij, 1988.

0 Comments