A Literary Shroud: Embroidering Derek Walcott’s Omeros

A bird stitching an epic: intertextuality and metaliterature in Derek Walcott’s Caribbean epic Omeros.

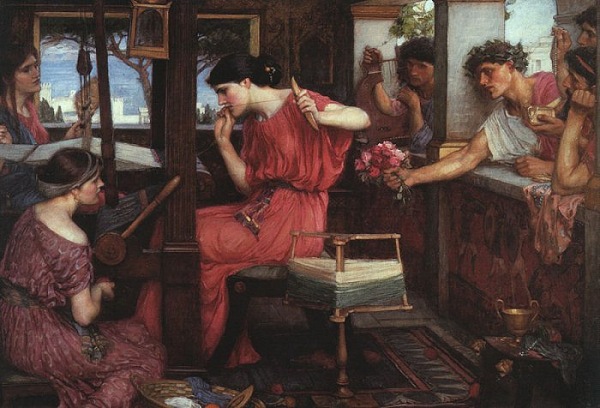

Have you ever compared your academic writing to weaving on a loom? Apparently doctoral students sometimes do so. As you may be well aware, textile work has been used as a metaphor for story-telling and writing since the beginnings of European literature. Our very word ‘text’ was derived from the Latin noun textus (‘tissue’), related to the verb texere (‘to weave’), and its use as a metaphor for ‘construction, combination, connection, context’ has been attested since Quintilian’s. In literature, Helen’s and Penelope’s weaving in the Iliad and Odyssey function as a metaliterary metaphor for the epics themselves.

Apart from weaving, other forms of textile work are also used as metaliterary metaphors. A professional reciter of for example the Iliad and Odyssey in later Greek history was called a rhapsodist, ‘a man sewing a song’, (ῥαψῳδός), i.e. someone who patches pieces of already existing songs together. In his Metamorphoses, Ovid furthermore lets Philomela convey her rape in embroidery sent to her sister Procne after her rapist, who happened to be her sister’s husband, had cut out her tongue.

Apart from textiles, poetry has been compared to birdsong at least since Aristophanes’ comedy Birds. This is also the case in the tale of Philomela. After the rape, she and her sister first revenge themselves on the rapist brother-in-law by brutally killing his and Procne’s son. At the end of the tale, Philomela and her sister manage to escape as birds. One of them is now the nightingale, like a poet lamenting the death of her son.

Birds on a shroud

It will not come as a surprise that the 20th century Caribbean epic Omeros (1990) contains some metapoetical embroidery. In this highly intertextual epic, author Derek Walcott brings Homer to postcolonial St Lucia much in the way Joyce in Ulysses took Homer to (post)colonial Dublin.

Fig.3. Derek Walcott in 2008. Photograph by Bert Nienhuis.

The narrator of Omeros, an alter ego of Derek Walcott himself, is a middle-aged writer living in the US, who visits his old mother on his native island St Lucia in the Caribbean. There he also meets with the ghost of his father, who died when he was little and who now sends him on a literary Odyssey. In a bar on the island he runs into the aged couple Dennis and Maud Plunkett, Walcott’s version of Odysseus and Penelope. Dennis, a retired British army officer and Maud, from Ireland, got married and settled on St Lucia after WWII. Despite their success, they are still suffering from the fact that they have never had a son. Maud is diagnosed with cancer and dies. Her coffin is covered by a shroud she had spent years embroidering herself.

Fig.4. The Caribbean island of St Lucia. Pixabay, 2013.

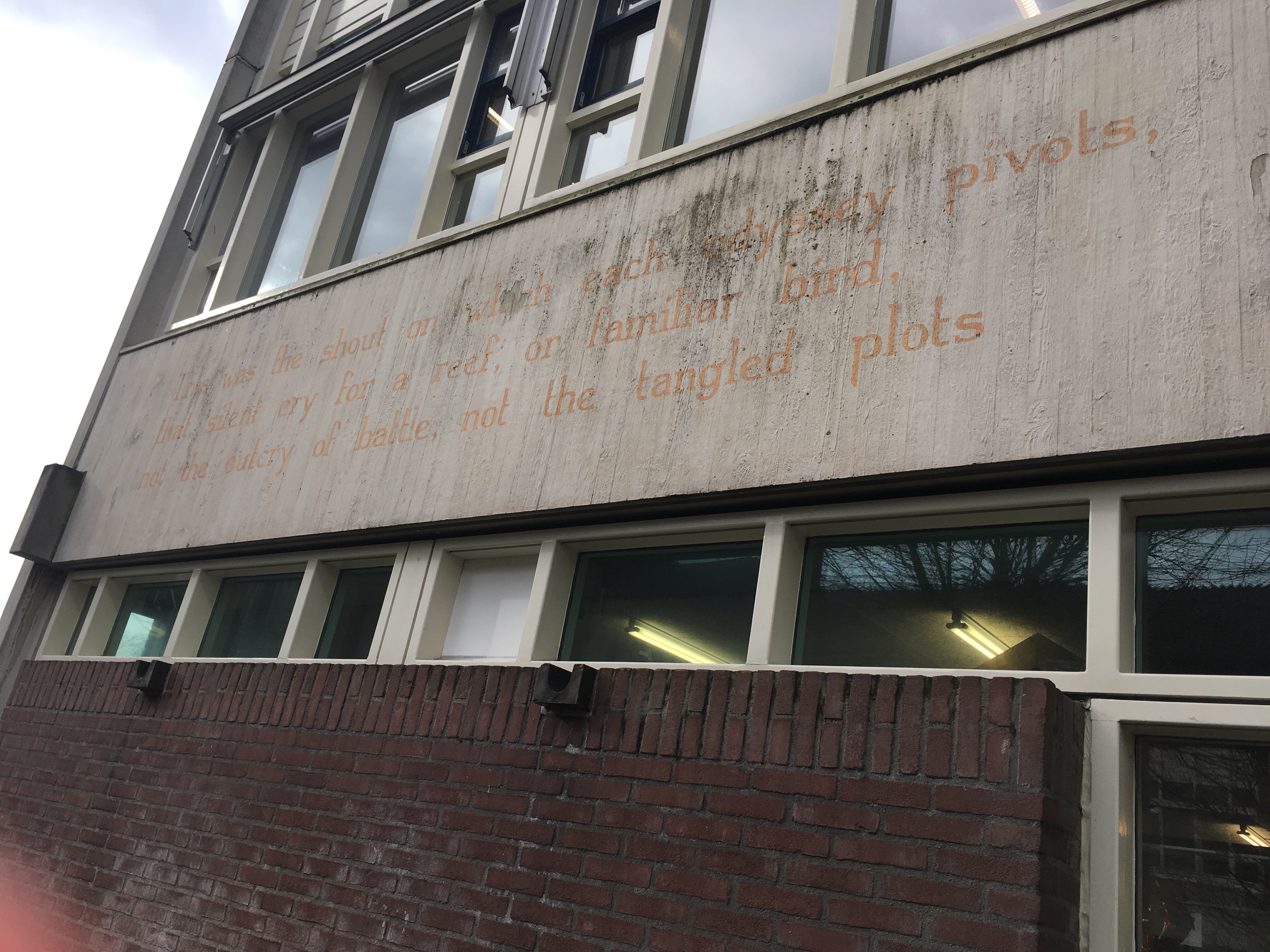

Fig.5. A few lines from Omeros at the Reuvensplaats in Leiden in 2007. Photograph by Lieke Smits.

Maud embroidered her shroud with birds from the main ornithological book of the West-Indies:

Maud with her needle, embroidering a silhouette

from Bond’s Ornithology, their quiet mirrored

in an antique frame. Needlepoint constellations

on a clear night had prompted this intricate thing,

this immense quilt, which, with her typical patience,

she’d started years ago, making its blind birds sing,

beaks parted like nibs from their brown branch and cover

on the silken shroud. Mockingbirds, finches, and wrens,

nightjars and kingfishers, hawks, hummingbirds, plover,

ospreys and falcons, with beaks like his scratching pen’s,

terns, royal and bridled, wild ducks, migrating teal,

pipers (their fledgling beaks), wild waterfowl, widgeon,

Cypseloides Niger, l ‘hirondelle des Antilles

(their name for the sea-swift) (XVI.ii).

The simile of the birds’ beaks and pens (nibs) explicitly identifies the shroud as a metaliterary symbol. Furthermore, Maud’s patient work implicitly evokes Penelope’s patient and metaliterary weaving of a shroud for her father-in-law, Laertes.

Quilting women are also a common element of Anglo-Saxon and Irish literature. For example, the Irish poet Eavan Boland frequently mentions textile work in in her poetry in order to throw light on the past lives of Irish women, stressing their poor working conditions. However, Boland also uses quilting as a metaphor for her own writing and thus for the life of an independent, modern, female poet.

Submission, creation or integration?

My question is now how to interpret Maud and her embroidery in Omeros. Is she an independent creator or the submissive woman of the colonial past? I found a strong intertextual clue for her sad death in the figure of Odysseus’ mother in the Odyssey. The fluid characters in Omeros, Caribbean as well as Greek, seem to be in a constant metamorphosis, changing roles and even shapes. The travelling narrator is Odysseus, on a quest around the world only to come back to his Ithaca, as well as Telemachus, desperately searching for a father. In a way, Maud and Dennis are his surrogate parents: ‘There was Plunkett in my father, much as there was / my mother in Maud’ (LII.ii). Therefore, Maud mirrors Odysseus’ mother, who died in his absence and whom he meets in the underworld. The narrator indeed attends Maud’s funeral.

Another clue can be found in the name Maud, familiar from Tennyson’s poem ‘Maud’ and the Irish Maud Gonne, the muse of the poet William Butler Yeats. Maud Plunkett thus appears as a maternal muse to the narrator of the poem. Indeed Derek Walcott’s mother may well have inspired Walcott’s poetical work. The subservient role of muse is confirmed by Maud’s work of copying birds from a book and putting them together. This resembles the ‘stitching’ of the Greek rhapsodists and indeed does not make Maud look like an independent craftswoman.

However, the symbol of the textile is expanded by the equally metaliterary notion of the birds. One of the birds is the black swift, the Cypseloides niger.

This swift is a central symbol in Omeros, representing the sign of the cross and, in its migrations, guiding the narrator in his Odyssey. It is striking that Maud’s embroidering is compared to the movements of this swift:

How often had he admired

her hands in the half-dark out of the lamplit ring

in the deep floral divan, diving like a swift

to the drum’s hoop, as quick as a curlew drinking

salt, with its hover, skim, dip, the vertical lift (XVI.ii).

Therefore, Maud ìs the swift, a kind of role swapping familiar to Omeros and reminiscent of Philomela’s metamorphosis. She now seems the muse as well as the auctor of the poem. Correspondingly, the embroidered shroud is for herself, rather than a service for someone else.

After Maud’s death, however, her role is taken over by the narrator, when he applies the stitching of the swift to his own work:

I followed a sea-swift to both sides of this text;

her hyphen stitched its seam,

(…)

Her wing-beat carries these islands to Africa,

she sewed the Atlantic rift with a needle’s line,

the rift in the soul (LXIII.iii).

Thus, it seems that Maud’s role in the poem is mixed. She is a traditional quilting wife, who produces her own shroud. She is copying someone else’s work, but also producing something new, in fact Omeros itself. She is muse and poet alike, integrating past and present, submission and independence. This not only represents Walcott’s vision on literature. The maternal figure of Maud has also helped Walcott to pay homage to his own ageing mother and to create Omeros as her literary shroud.

Further reading

Feuth, Amaranth. “Onderwereld en schrijverschap: katabasis en droom-visioen in Derek Walcotts Omeros.” Kleio. Tijdschrift voor oude talen en antieke cultuur of the Catholic University of Leuven, 44.4 ( 2015): 146-62.

© Amaranth Feuth and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Amaranth Feuth and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments