A Painter, a Collector, and a Horseshoe Crab

On full moon nights this time of the year, an extraordinary sight can be witnessed on beaches all over the U.S. East Coast. Thousands of horseshoe crabs come ashore to mate and lay eggs.

The horseshoe crab fascinates us today, but this fascination already begun in the early modern period.

All is not well in the world of the horseshoe crab. This remarkable animal has been around some 450 million years and has survived five mass extinctions, but is now under threat of mankind. Reasons given for the disturbing death rates among these ‘living fossils’ are the rising sea level and a shortage of breeding grounds. Besides that, the pharmaceutical industry has a keen interest in the horseshoe crab because of their blue blood, which is used for the detection of bacterial endotoxins in new pharmaceuticals.

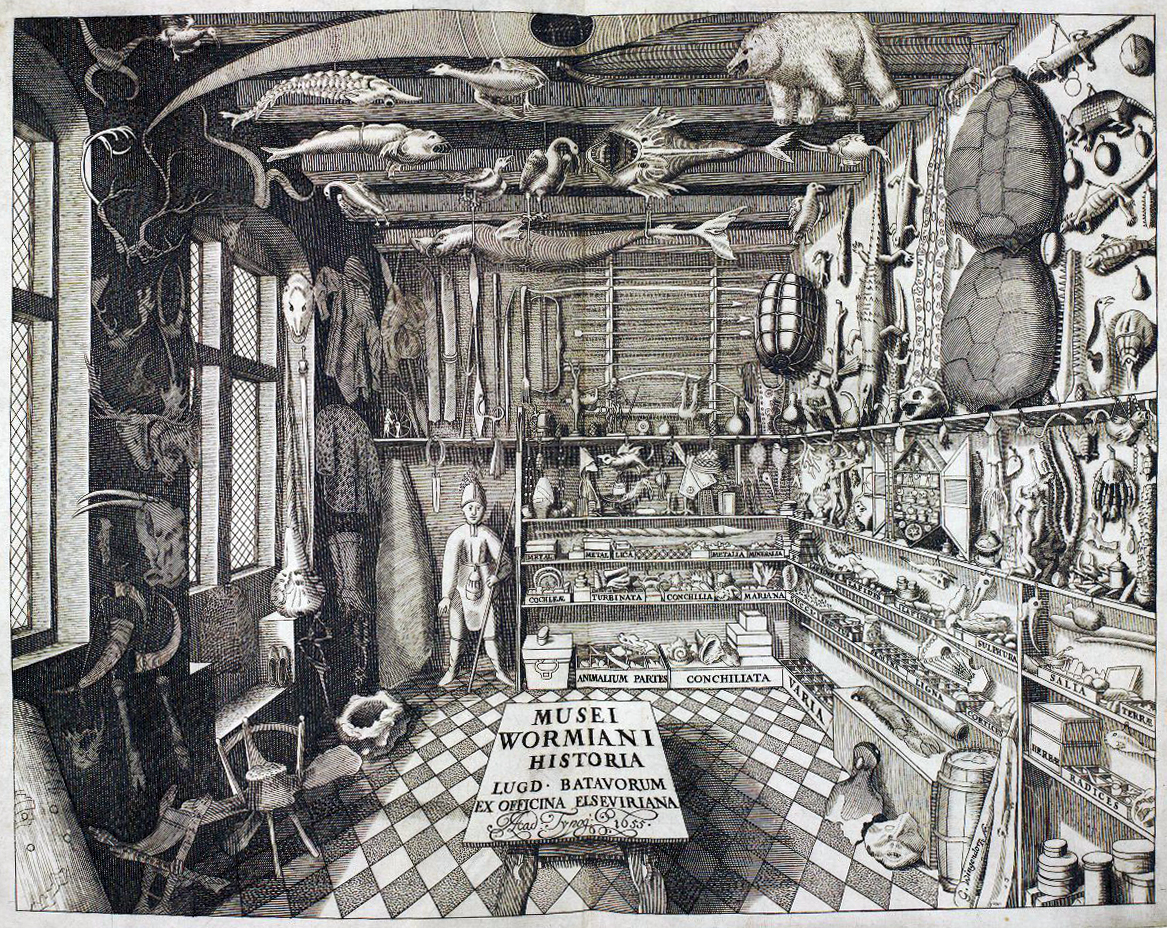

Ole Worm, Museum Wormianum, 1655, frontispiece, with a horseshoe crab on the right side wall

Not just contemporary biologists are fascinated by the horseshoe crab. Centuries before this year’s breeding season, people had already taken a keen interest in this remarkable animal. There are four different species of horseshoe crabs, three of which occur in East Asia and one on the East Coast of the U.S. So before the early modern explorations of East Asia and the New World, no one in Europe had ever seen a horseshoe crab. With their tough carapace and long, pointy tail, they must have awed European travellers. In the late sixteenth century we find the first evidence of dried specimen that were being shipped to Europe, while at the same time, the first European images of the horseshoe crab were made. During the following centuries dried horseshoe crabs became prized possessions of naturalia collectors, while they also figured in paintings, prints, and book illustrations. One example is a painting from Antwerp from 1617. What follows is a story about this painting with three main characters: a painter, a collector, and a horseshoe crab.

The horseshoe crab painted

Frans Francken the Younger (1581-1642) from Antwerp depicted a horseshoe crab in at least three paintings: twice in so-called gallery pictures (a.k.a. paintings of collections or ‘constcamer’ paintings) from 1617 and once in an allegory from 1629. Around 1620, two horseshoe crabs were also depicted by another Antwerp artist, Frans Snyders (1579-1657), in a painting of a fish stall, a place where they, of course, could never be found in reality. These were among the earliest European depictions of the horseshoe crab, and, to the best of my knowledge, the very first ones in the medium of oil paint.

In the first decades of the seventeenth century, horseshoe crabs were still very rare in collections and the number of images of the animal could be counted on the fingers of one hand. None of these images seems to have served as an example for the Antwerp painters: they are too schematic or not in colour. Francken’s early and highly naturalistic colour depiction of the horseshoe crab in The Cabinet of a Collector is particularly remarkable. Did the artist base his depiction upon a real specimen? And could he have seen a dried horseshoe crab in an actual collection?

Detail of: Frans Francken the Younger, The Cabinet of a Collector, 1617 (signed and dated), oil on panel, 77 × 119 cm, The Royal Collection England (for full image, see: https://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection/405781/the-cabinet-of-a-collector)

The genre of the gallery picture was invented in Antwerp in the 1610s and remained unique for that city in the first decades after its invention. The early examples depict objects from art and nature and are a reflection upon the culture of collecting. Many Antwerp citizens indeed amassed impressive collections of artificiala and naturalia, as we know from probate inventories. Rarely, however, can actual collection be linked to gallery paintings. But in the case of Frans Francken’s The Cabinet of a Collector from 1617 with the horseshoe crab (now Royal Collection England), I want to argue that it is likely that Francken depicted a collection he knew in Antwerp – or used it as an inspiration at the very least. And the horseshoe crab is a crucial part of the puzzle.

A collection with a horseshoe crab

In the collection of the Antwerp notary Gillis de Kimpe (d. 1625) we find the mysterious description of a ‘zeespinnecop’ (sea spider). When I first read this, I had no idea what sort of animal it could be. A search into early modern Dutch natural history books and catalogues of other collections learnt that ‘zeespinnecop’ or ‘zeespin’ was the common early modern Dutch name for the horseshoe crab. We find the name in the catalogues of the collection of Leiden University and in Georg Rumphius’s D’Amboinsche Rariteitenkamer, for instance. Moreover, a watercolour of a horseshoe crab by the Dutch artist Pieter Holsteijn the Younger (1614-1673) bears the inscription (perhaps by the artist himself) ‘zeespinnekop’.

Gillis de Kimpe was one of Antwerp’s most wealthy collectors. He had a library of over 1,000 books; over 2,000 medals, coins, and cameos (including antiques); 144 paintings (by famous Netherlandish masters, including Jeroen Bosch, Quinten Massijs, Jan Brueghel, and Lucas van Valckenborch); hundreds of drawings and prints; scientific instruments; and a wonderful assortment of naturalia. Among his naturalia we find shells, corals, agates, mountain crystals, horns, coconuts, so-called ‘Indian flies and fruits’, ostrich eggs, the skeleton of an animal, a decorated nautilus shell, a blowfish, turtle shells, and the specimen that is of special interest here: the ‘zeespinnecop’, or horseshoe crab.

As common as the horseshoe crab was in natural history collections in the second half of the seventeenth century, it was just as rare to own one in the first half of the same century. At the time that Francken painted his picture, 1617, we know of no other horseshoe crab in an Antwerp collection than the one owned by De Kimpe. So was this perhaps the specimen depicted by Francken?

The painter and the collector

In the summer of 1625, De Kimpe lay sick in his bed. On July 14 he summoned a notary to his house to draft his last will. On this occasion, he appointed two executors of his last will and one of them was none other than… Frans Francken. It meant that the two men had a good relationship, while De Kimpe may also have put faith in Francken because of the painter’s expertise or connoisseurship with regard to the large collection.

Willem Hondius after Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Frans Francken the Younger, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (public domain)

And there is more. In Francken’s painting, next to the highly accurate horseshoe crab, another exotic object is hanging on the wall: a beautiful Indonesian dagger, a so-called kris. In De Kimpe’s inventory, the ‘zeespinnecop’ is listed right after an ‘Idiaenschen poinjart’, an Indian dagger, which was probably such a kris from Indonesia. There are only two other Antwerp inventories from this period that include descriptions of a kris. So, again, this is an extraordinary collectable at this point in time. Besides, the fact that the two objects are listed one after the other in the inventory indicates that they were kept or hung next to each other.

So, are there any other objects in The Cabinet of a Collector that can be related to De Kimpe’s collection? Among De Kimpe’s substantial number of objects listed as ‘Indian’ was an ‘Indian lacquer box’, which may very well have been (similar to) the lacquer box in the painting. One can also think of the shells, drawings, and coins. Also, De Kimpe owned ‘een copyken naer Breugel op coper van Beestkens in ebbenlyste’ (a copy after Breugel on copper of animals in ebony frame), which sounds a whole lot like a description of the pictures hanging on the right side of the wall in Francken’s painting. These are more generic descriptions, but all in all, I think there are good reasons to link Francken’s painting now in the Royal Collection to the collection of his acquaintance De Kimpe.

Antwerp collectors like De Kimpe and Antwerp painters like Francken lived and worked in a city with a lively collecting culture. They were fascinated by the variety and abundance of nature, which finds expression in paintings - from gallery pictures and allegories to fish markets. In their own ways, through ownership, observation, and depiction, they were connoisseurs of art and nature.

Further reading:

Marlise Rijks, ‘A Painter, a Collector, and a Horseshoe Crab. Connoisseurs of Art and Nature in Early Modern Antwerp’, Journal of the History of Collections, forthcoming.

0 Comments