A Theatrical Whodunit

How did Calderón’s popular play 'La vida es sueño' come to the Low Countries? It seems that the Flemish-Portuguese printer Paulo Craesbeeck is responsible for this. In 1647, he published an anthology of Spanish plays, including Calderón's masterpiece.

One of the most famous plays translated from Spanish is Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s La vida es sueño, first published in 1635. It was so popular that it was translated in many European languages. In 1647, the first Dutch translation was made in Brussels by a rather anonymous author with the name Schouwenbergh. Frans Blom discusses in his forthcoming article ‘The Pearl from Spain: Calderón’s La Vida es Sueño in the Dutch speaking territories, and beyond’ that the name Schouwenbergh could be someone from the Brussels family Van den Bergh, although it is as likely that the author made a pun on the Dutch word for theatre (‘Schouwburg’).

Despite the anonymity of the author, the play also appeared on stage in Amsterdam seven years after the Brussels adaptation was first published. The datasystem ONSTAGE tells us that the play was one of the most popular plays of Spanish origin that was translated in Dutch. After the Dutch adaptation of La vida es sueño proved that it could hold its own in both Brussels and Amsterdam, travelling companies toured with the play through the Dutch Republic. There appeared, furthermore, a German translation in 1666 for the theatre market in the Holy Roman Empire.

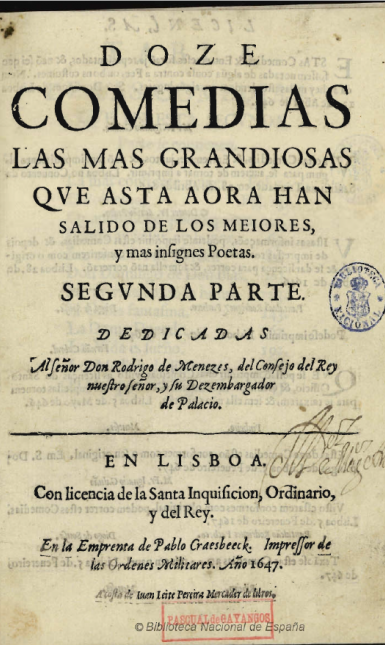

The Nachleben of the text is clear, but how Schouwenbergh got his hands on the Spanish original in the first place has been a matter for conjecture for a long time, until yesterday I coincidentally found a facsimile of Doze comedias las mas grandiosas que asta aora han salido de los meiores, y mas insignes poetas. Segunda parte (1647) on the digital environment of the Biblioteca Nacional de España. The title of the anthology reads in English: “The twelve grandest comedias, which until today have been emanated from the best and most prominent poets. The second part”. And thus, the anthology naturally also contains Calderón’s La vida es sueño. Furthermore, the impressum states that the anthology was printed in Lisbon. This is not strange in itself, since this happened more often. However, something else caught my eye. To my surprise, the publisher of this anthology has a Flemish-sounding surname: his name is Pablo Craesbeeck.

The Anthology

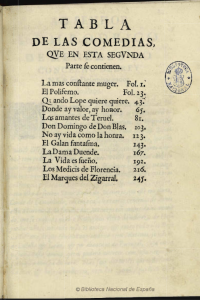

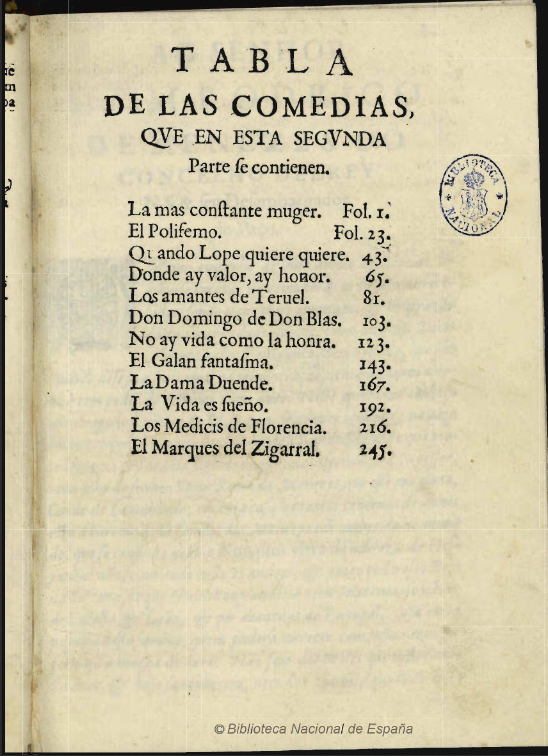

This discovery is interesting for two reasons. First, the anthology itself: as with all anthologies of Spanish comedias, they typically contain twelve comedias. Sometimes, these comedias were all written by one author, but at least as often the anthologies are an overview of what the printer or (as in this case) the funder Juan Leite Pereira believed to be the best comedias from different Spanish playwrights.

As such, the 1647 anthology contains twelve different comedias by famous playwrights, such as Lope de Vega, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Antonio Mira de Amescua, Juan Pérez de Montalbán, and Juan Ruiz de Alarcón y Mendoza. The interesting part about this is, however, that seven of these twelve comedias have also been translated in Dutch, if not more. These plays belonged to the more popular plays that were staged in the theatres of Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Brussels. The plays were transferred and adapted, sometimes with the help of a technical translator and most notably with the help of the Sephardic Jew Jacobus Baroces. These seven plays are as follows:

Amsterdam

- Juan Pérez de Montalván, La más constante mujer (before 1638); translated by Baroces and adapted by Leonard de Fuyter as Stantvastige Isabella (1651);

- Diego Jiménez de Enciso, Los Medicis de Florencia (before 1634); translated by Baroces and adapted by Joan Dullaart as Alexander de Medicis (1653);

- Calderón, El galán fantasma (1637); translated by Simon Engelbrecht and adapted by David Lingelbach as De spookende minnaar (1664);

- Calderón, La dama duende (1629); adapted by Andries Peys as De nacht-spookende joffer (1670) and another time by Lodewijk Meijer as Het spoockend weeuwtje (1670).

Antwerp

- Lope de Vega, El castigo sin venganza (1631); adapted by Antonio Francisco Wouthers as De verliefde stiefmoeder (1665).

Brussels

- Calderón, La vida es sueño (1635); translated and adapted by Schouwenbergh as Het leven is maer droom (1647); reprinted in Amsterdam as Sigismundus, prince van Poolen (1654);

- Alonso de Castillo Solórzano, El marqués del Cigarral (before 1647); translated and adapted by Claude de Grieck as Don Japhet van Armenien (1657).

This overview suggests that the texts in the anthology could have been used as source texts for the Dutch adaptations. This would mean, then, that the anthology was also shipped to the Low Countries and subsequently sold there. This suggestion is, furthermore, supported by the Dutch-Flemish connections of the printer Pablo Craesbeeck.

If this is true, then this could also have implications for the five other plays in this 1647 anthology. It is possible that these comedias were also translated in Dutch, although it is as yet unclear whether this also truly happened. The same can be said for the nine entremeses in the anthology. It is possible that these were adapted as Dutch farces, such as with Cornelis de Bie’s Klucht van Roelandt den Clapper, geseyt Hablador Roelando (1673). This farce is an adaptation of Miguel de Cervantes’ Los habladores.

The Craesbeeck Publishing Dynasty

But what was the role of the printer Pablo Craesbeeck in this act of cultural exchange? In Portuguese, Pablo Craesbeeck is better known as Paulo Craesbeeck. Together with his brother Lourenço, he had inherited the printing business of his father Peeter Craesbeeck (c. 1552–1632). Father Craesbeeck was likely born in Louvain in present-day Belgium and in 1580—at the age of twenty-eight—he was employed by the famous publisher Cristophe Plantin in Antwerp as an unpaid apprentice. After six years, he became a full-time setter in Plantin’s business.

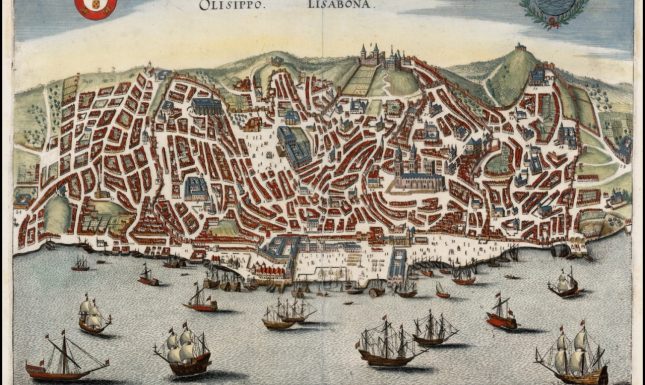

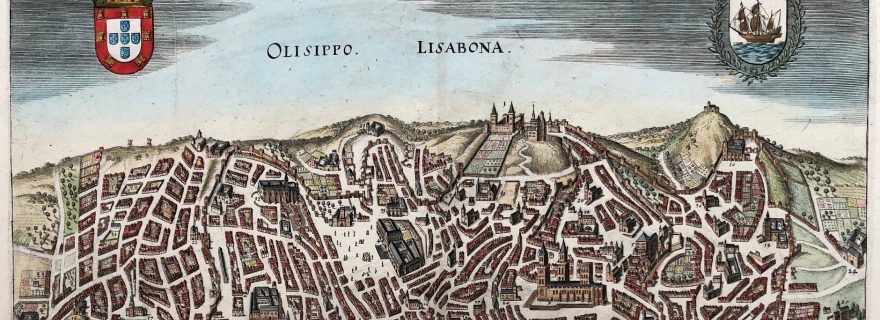

On 2 May 1592, Craesbeeck sr. married the half Antwerp, half Portuguese Susana Domingues and the young family emigrated to southern Europe because of religious and personal reasons. Peeter Craesbeeck first tried to start a publishing company in Madrid, but this enterprise failed. Yet, this period in Madrid offered the basis for his later Spanish publications. Sometime before 1597, he finally settled in Lisbon.

Already after one year, he obtained the right to publish the work of the most famous Portuguese poet Luís de Camões from his competitor Manuel de Lyra and he expanded his business to include many other imposing works of literature. By the time of his death in 1632, Peeter Craesbeeck had become the most important publisher of Portugal and he held great prestige among all strata of society.

His sons continued their father’s business. Lourenço Craesbeeck set up shop in the university town of Coimbra, while Paulo stayed in Lisbon. Paulo relied more on his father’s fame, bore his father’s title of Impressor Real, and was the more productive publisher of the two brothers.

In this environment, the anthology was published in 1647, the same year as Schouwenbergh translated La vida es sueño in Dutch. The Flemish heritage of Paulo Craesbeeck must have meant that he had contacts in Antwerp, which ensured that the anthology was shipped to the port of this Flemish metropolis, after which it was further distributed in Brussels and Amsterdam. In these cities, Dutch and Flemish playwrights eagerly took the opportunity to adapt the plays that this anthology contained. Via this route, the original Spanish text of Calderón's La vida es sueño could have been made available in Brussels. As such, Schouwenbergh might have used this specific version of the text for his Dutch translation Het leven is maer droom.

Further Reading

Jautze, Kim, Leonor Álvarez Francés, and Frans R.E. Blom. ‘Spaans Theater in de Amsterdamse Schouwburg (1638–1672). Kwantitatieve en Kwalitatieve Analyse van de Creatieve Industrie van het Vertalen’. De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in Interdisciplinair Perspectief 32.1 (2016), 12–39.

Rousseeuw, Boris. ‘De drukkersdynastie Van Craesbeeck: Het verhaal van een familie’. De Boekenwereld 3 (1986–1987), 14–16.

Sullivan, Henry W. Calderón in the German Lands and the Low Countries. His Reception and Influence, 1654–1980. Cambridge Iberian and Latin American Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

© Tim Vergeer and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Tim Vergeer and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments