Academic research can be emotional as well

Last week, Rick Honings, Olga van Marion and Tim Vergeer presented their new book on dead children in Dutch Literature. In this post, Tim reflects on writing about a new genre and the particularities of the book presentation.

It is maybe the oddest thing to celebrate a book about dead children (in literature); and yet, it is a long-held Dutch tradition to present a new book during a symposium or a book presentation, which some people – including myself – like to call a boekdoop, the christening of a book. Thursday 26 April in the afternoon, Van Constantijntje tot Tonio. Het dode kind in de Nederlandse literatuur was officially introduced to a large group of interested people, students, and family. And it was and still seems to be a big hit in the media and elsewhere.

The Sublimity of the Dying Child

Why the fascination with this subject? Why did so many people attend the symposium? The subject does not particularly sound inviting nor does it sound like a fun afternoon. As editors, we think that the sublimity of it all attracts our attention as humans: the horrible thought of losing a child fascinates. Maybe more than in any other genre of literature, people find comfort or solace: either you have lost a child and you want to understand your own sorrow, or you do still have children and you live in the ongoing fear that one of your children will die.

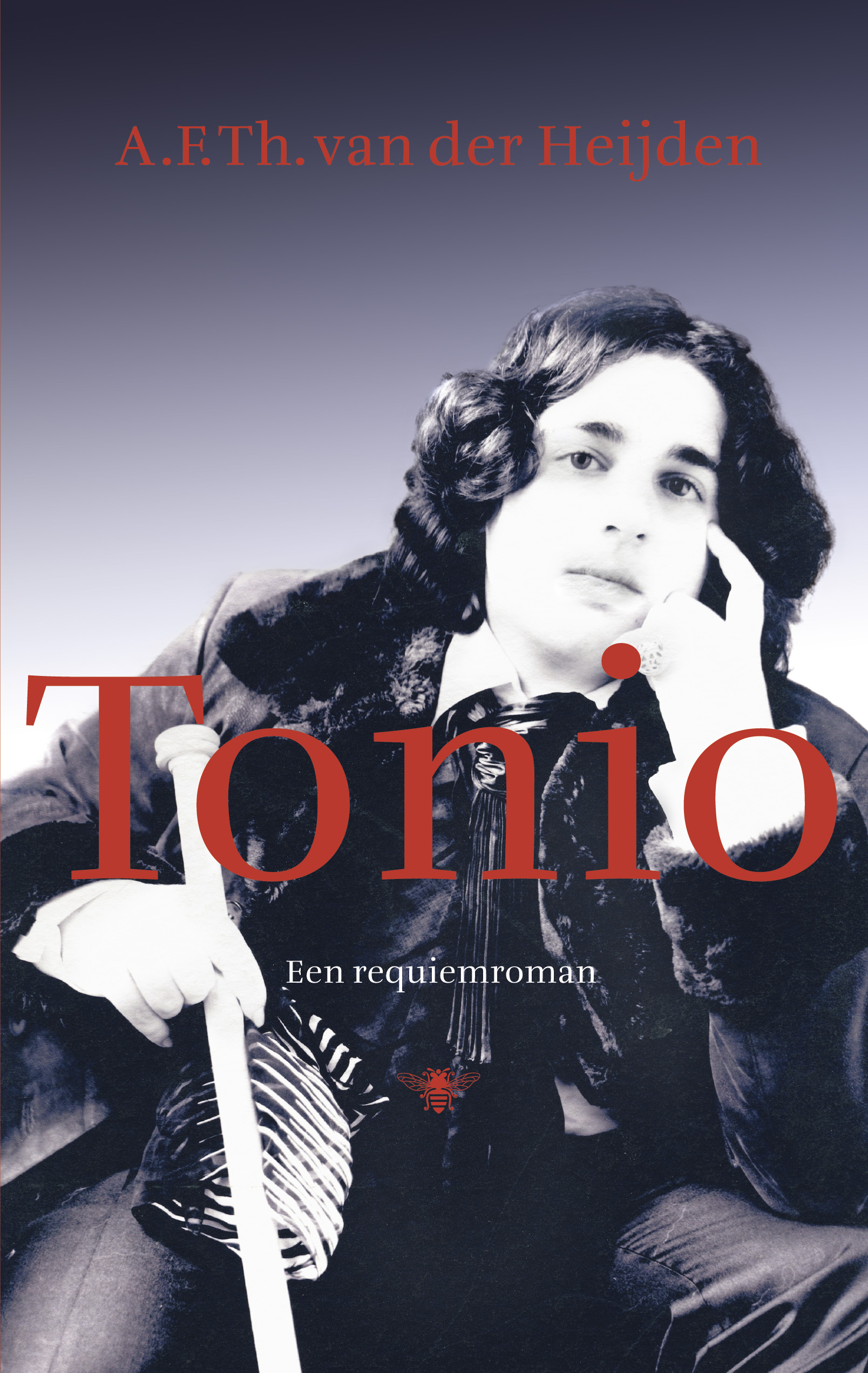

And so, while reading Tonio by A.F.Th. van der Heijden we learn to accept the possibility of losing a child. Frans-Willem Korsten calls it, therefore, proto-traumatic in his contribution to Van Constantijntje tot Tonio: losing a child is a traumatic experience, but reading about a dead child which is not your own, trains you to accept the loss in advance. And when you lose a child, you recognise yourself in Van der Heijden, Thomése, Enquist and many others.

Cover of A.F.Th. van der Heijden's Tonio. Een requiemroman (2011).

The Personal Experience

What is more special about this book is that several contributors write about their own experiences with child death or the fear of losing their own children, or about their parents losing their children. During the symposium, Korsten did for example a little experiment: by rereading what he wrote out loud to the public, would he then feel the emotions he felt when writing the piece? In turn, Onno Blom wrote in Van Constantijntje tot Tonio that writing about Wolker’s Eva was the hardest thing. When he was writing about 1951 in Jan Wolker’s biography, Blom’s daughter was the same age as Eva was back then. It seems that academic writing about this genre is near to impossible. But is that wrong?

I am inclined to say not. The first time that I was completely overwhelmed by literature was during my first year course about seventeenth-century literature. Olga van Marion, who is now my co-supervisor as well, recited Joost van den Vondel’s ‘Kinder-lyck’ (1632) about his dead son Constantijn. It was the first time that I experienced what it meant to ‘live literature’. She experienced back then the emotions felt by a mourning father, and last Thursday she did as well. I will quote the poem, but in Dutch, because translating would be a severe crime:

Constantijntje, ’t zaligh kijntje,

Cherubijntje, van om hoogh,

D’ydelheden, hier beneden,

Vitlacht met een lodderoog.

Moeder, zeit hy, waarom schreit ghy?

Waarom greit ghy, op mijn lijck?

Boven leef ick, boven zweef ick,

Engeltje van ’t hemelrijck:

En ick blinck ’er, en ick drincker,

’t Geen de schincker alles goets

Schenckt de zielen, die daar krielen,

Dertel van veel overvloets.

Leer dan reizen met gepeizen

Naar pallaizen, uit het slick

Dezer werrelt, die zoo dwerrelt.

Eeuwigh gaat voor oogenblick.

And I still know the poem by heart.

I think, furthermore, that there is no one who would say that they actually hate ‘dead child’s literature’, though quite some people say that they cannot read it because it is too horrible. No one says, however, that such books are qualitatively speaking bad, and if a reviewer dares to give a literary judgment, (s)he is immediately ostracized; I know that I did when reading the reviews on Enquist’s books about her daughter Margit. Is that, however, because the personal experience makes it impossible to pass an actual judgment or do we all think the same? Is it maybe an innate trait of human life to feel compassion? I do not know.

Cornelis Cornelisz. van Haarlem, De kindermoord in Bethlehem, 1590, Rijksmuseum.

What do we learn from this?

Being in the business of literature, we deal with shocking, compassionate, fearing, emotional, hateful characters and we were once moved by their stories and every time we read about them and try to understand them a little bit better, we engage with them. We become subjective and feel inclined towards one or another character, while we hate the other. And still, we artificially force ourselves to obtain the objective perspective. Do we not destroy a little bit of our own experience then? Can ‘dead child’s literature’ teach us to feel a little bit more when doing academic research? And should we want that?

Further reading

Honings, Rick, Olga van Marion & Tim Vergeer (eds.), Van Constantijntje tot Tonio. Het dode kind in de Nederlandse literatuur. Hilversum: Verloren 2018.

0 Comments