All books are equal, but some books…

When I tell people that I work as a scholar in book and publishing studies, it’s often not immediately clear to people what aspects of the book I would then study. In this post, I try to explain some key concepts through George Orwell's Animal Farm.

“You’re a researcher in book and publishing studies? What’s your favourite book, then?” If I’d got a euro for every time I got asked that question, working as a teacher and researcher in Book & Digital Media Studies would’ve made me rich. The question contains a hidden metaphor, because the asker usually does not mean to enquire which set of bound pages I love most – but which story, delivered in text. The codex-shape in which texts have usually been transmitted for the past five centuries has settled in our collective minds, to such an extent that we usually do not even distinguish between the ideas that are communicated and the form they are packaged in; content and carrier have merged.

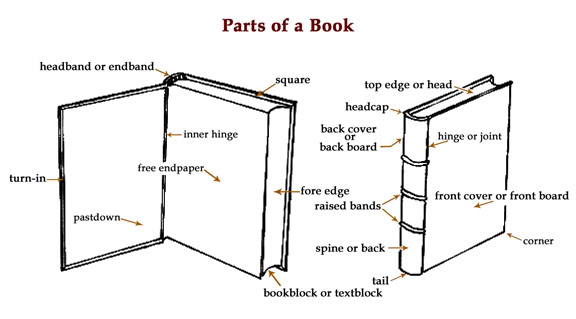

[Fig.1 ‘Parts of a book’, relating only to the physical carrier, the codex. Image: Wikimedia Commons.]

Many scholarly disciplines in the Humanities study textual content: literary scholars, for instance, focus on the manifestation of ideas in text by studying its particular characteristics, usually in comparison to other texts. Historians analyse written testimonies from past times, as traces of the human experience then. Book and publishing studies, however, do not focus predominantly on the textual contents of books, but combine inquiries into the contents of the book with an analysis of their form, their function in society, and the interplay between these factors.

Clarification: Animal Farm from a literary and book studies perspective

Perhaps the difference becomes clear in an example, of George Orwell’s allegorical novella Animal Farm. In this fable, pigs take over control of a farm by ousting the farmer to free the animals of tyranny; when they’re in power, however, they introduce rules that advantage pigs and let all others work even harder than before. If you would study Animal Farm for a literary studies class, you could focus on for instance antropomorfism, allegories, and writing style in the book, and how these contribute to the political ideas Orwell means to express. For this, it would not matter too much whether you brought a new Penguin edition, a third-hand copy from the seventies, or online access to the Project Gutenberg-version to class, as long as you could read the original and full text.

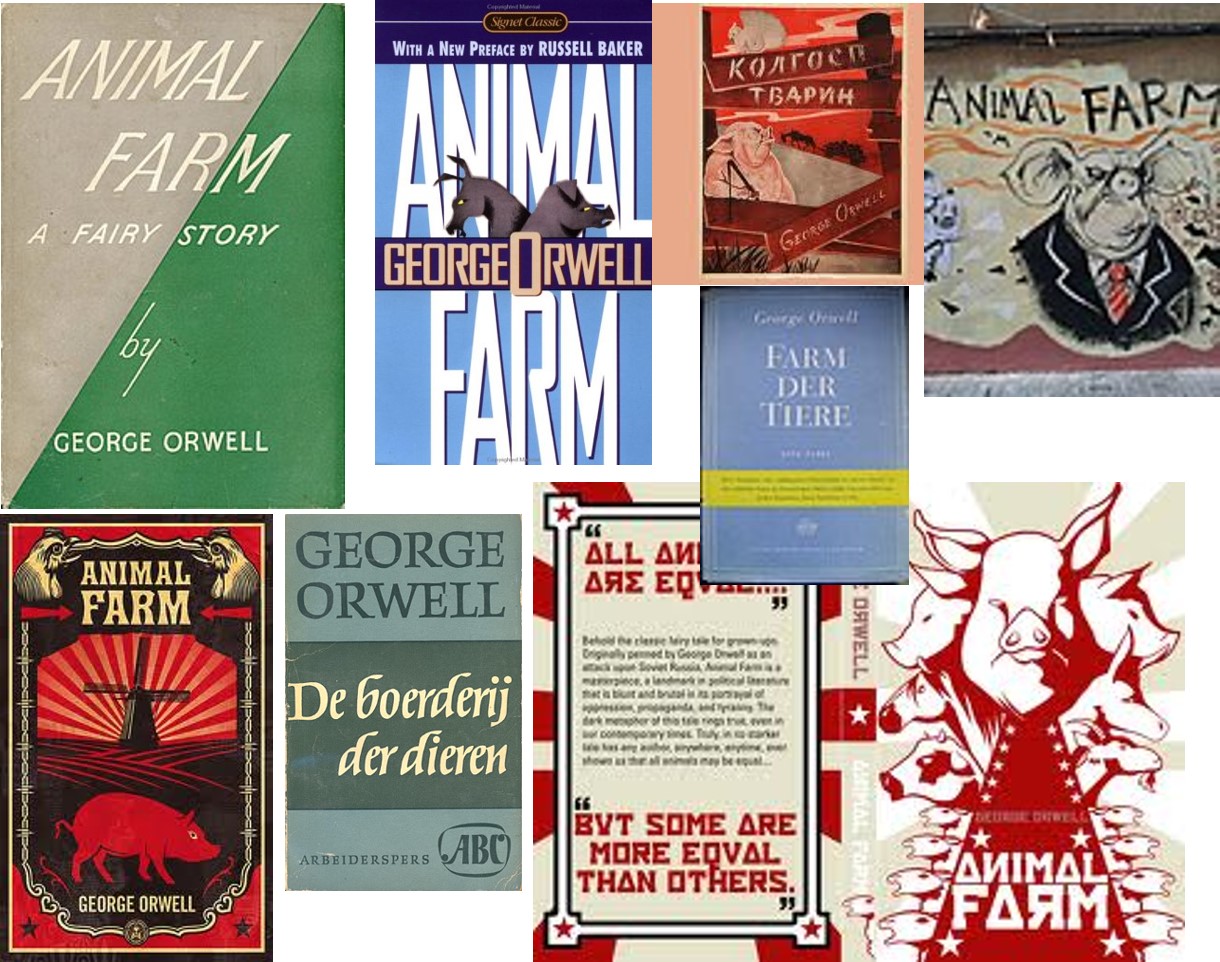

[Fig.2: Covers of editions and translations of Orwell’s Animal Farm. My collation; all images via Wikimedia Commons].

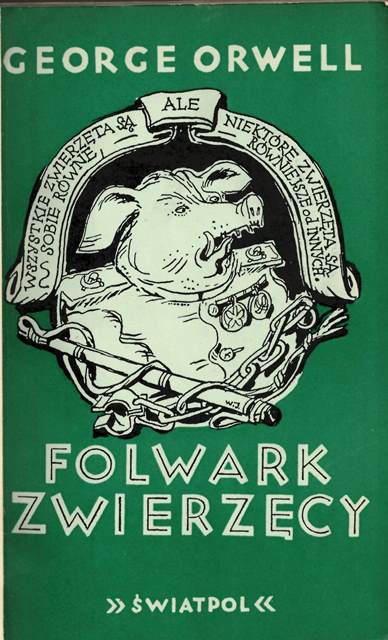

From a book studies perspective, you would not have to bring the text to class at all. We could focus on the circumstances that made it difficult for Orwell to find a publisher; after all, he was already a famous author and he finished the tale in 1943, but it was published only in 1945 by Secker and Warburg, not his usual publisher. We could focus on censorship in the UK in the ‘forties. Or we could analyse the networks that made immediate illegal translations possible, like the 1947 Polish edition, which was to be smuggled into the U.S.S.R. All this, we could do without discussing the story in detail: for book studies purposes, we should globally know about the contents of the book, but only in relationship to the economic, political and cultural circumstances surrounding it, and the material form it could be produced in.

Fig. 3: Animal Farm in the 1947 Polish translation. Image: British Library, BL012642.

Book scholars, thus, employ an interesting dual perspective: we study the material manifestations of ideas in text, and of texts in books; and the ways these material carriers make their way in society. Curiously enough, books have always been cultural artefacts on the one hand, but also economic products that are created and sold in a competitive market – ‘Words and Money’ (not coincidentally the title of an influential study of publishing, by André Schiffrin). Research into the production, dissemination and consumption of books in a particular time and place, current or historical, thus takes a basic understanding both of the literary and cultural discourse in which the book emerges, as well as knowledge of book-production technologies such as printing presses, but also the economic and political factors that would influence trade.

Merchants of Culture – in what form?

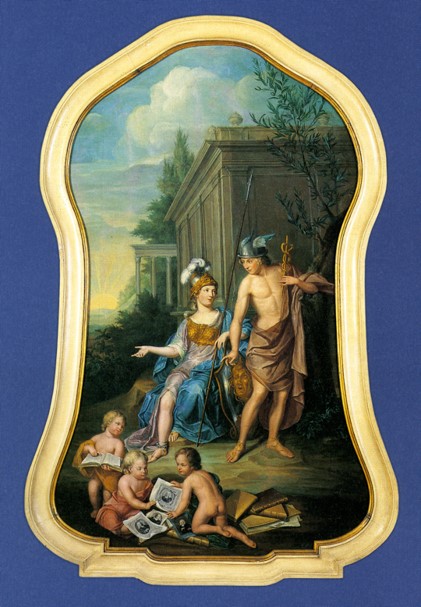

Although book history as a scholarly discipline first emerged only in the 1950’s, publishers have long embraced their split personality in this regard as ‘Merchants of Culture’ (another influential study of publishing, by John B. Thompson). Around 1750, Samuel Luchtmans, a Leiden publisher and direct predecessor to scholarly publisher Brill, had himself and his wife Cornelia painted in an allegorical portrait: it depicts their family firm as the marriage between Pallas Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, and Hermes, the demigod of commerce. Their three young sons play at their feet with books, the product of that marriage.

[Fig.4: Family portrait of publisher Samuel Luchtmans I, by Nicolaas Reyers, appx. 1750. Painting in the private collection of Royal Brill N.V., image via Brill: 325 years of scholarly publishing (2014) (https://issuu.com/brillpublishing/docs/brill_325_english_total_-)]

But all this begs the question: what is a book? In the eras from Luchtmans to Orwell, this was relatively straightforward: a book consisted of a cover of sorts, containing pages of printed text that are bound together somehow – how many pages, that was up for debate (Dutch law requires 8 for tax purposes; UNESCO lays the threshold at 50). The digital medium has made things much more complicated, as Animal Farm can once again illustrate.

Orwell in e, audio, and videogame

Today, the celebrated fable is available in many editions: hardcover and paperback, with or without illustrations, added materials, or study questions – and as an e-book. Here, the concept of pages has been let go, and font size can be adjusted; the original cover has been retained only as the book’s thumbnail on the e-book sales platform. Would you still consider this a version of the book? What about the audiobook, then, that contains Orwell’s full text narrated by a classically trained actor? How about Animal Farm on serialbox.com, that allows you to switch between reading the e-book and listening to the audio version? And the Android app that features written text and audio fragments – but also shows inescapable advertisements overlaying your reading? The online gameplay that ‘combines story choices and running the farm, giving players a chance to experience the consequences of their decisions first hand’?

[Fig. 5. Animal Farm app for Android, by Freebooks Editora. Screenshot from Google Playstore]

Likely, you will have stopped calling some of these new forms ‘books’ at some point, even though they’re all manifestations of text. Yet equally likely, that cut-off point differs between people, dependent on their attachment to print, their experience with audio and online reading, or other reasons. The classical definition of a book has had five centuries to settle its impression in our culture and our collective minds, but we rarely think about the impact it has made in our Western culture. That makes it an exciting medium to study. But it’s even more exciting, in my opinion, to explore the new forms for the traditional book, and analyse how they will take root in our culture in the years to come. And that is Book & Digital Media Studies.

[1] Recent scholarship convincingly argues that the Greek saw Hermes primarily as the gods’ messenger, while the Romans honoured Mercury as their god of trade, but that the two interpretations often get wrongly conflated in or modern view. The same has evidently happened in this Enlightenment portrait.

0 Comments