Anke Bangma: “Renewal can also be found in reinterpreting the historical."

In this post, Anke Bangma tells the LUCAS blog about strategical approaches she has undertaken toward the inclusion of contemporary Indonesian art within the national collection of The Netherlands.

Museums, and most importantly ethnographic museums, have been going through some significant changes in the past decades. In the postcolonial momentum, museums have had to procure novel ways to approach their collections. One way has been through the incorporation of contemporary art. Anke Bangma, recently appointed Artistic Director of TENT in Rotterdam , and former curator for Photography and Contemporary Art at the National Museum of World Cultures, told the LUCAS blog about strategical approaches she has undertaken toward the inclusion of contemporary Indonesian art within the national collection of The Netherlands.

Anke Bangma. Photocredit: Aad Hoogendoorn, Picture courtesy of TENT Rotterdam

I met Anke Bangma (b. 1969) in 2013, on the occasion of the opening of Indonesian artist Maryanto (b. 1977) at Heden Gallery, in Den Haag. Later, I got to know that Maryanto’s work had been purchased by the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam. This sparked my curiosity: how are these new acquisitions framed within the museum? In 2013/4 the Tropenmuseum (Amsterdam), the Africa Museum (Berg en Dal) and the Museum Volkenkunde (Leiden) merged to form the National Museum of World Cultures. So, Anke and I talked about the current setting and the relation with Maryanto’s work.

Opening of Maryanto’s show at Heden gallery, Den Haag, 25 October 2013

LV. You have been curator for contemporary art at the Tropenmuseum and curator for photography and contemporary art of the National Museum of World Cultures, a position that resulted from a major institutional merge. Can you reflect a bit on this institutional change and let the public know more about what resulted from this new setting?

AB. To start, it encouraged various teams to work together. To me, two positive aspects came out: firstly, the collections were brought together in a national collection. If you observe the contents of each collection, it makes sense. The collections complement and enrich each other; it’s like a “pool” of human creativity – from archaeological remains to modern art, from architectural models to early photography, from royal dress to everyday objects. Secondly, once the curatorial team became one, we had to think how our specific knowledge could be used and how we could learn from each other. The team is interdisciplinary; we have regional specialists, archaeologists, anthropologists and contemporary art specialists. Out of this encounter, we began to develop new museological approaches.

LV. And how does contemporary art participate in this setting?

AB. In the Tropenmuseum, the idea was that contemporary art could help innovate the museum’s role. In the current setting, this idea has been broadened: we can and should work with the past. This allows for a transdisciplinary effort. Renewal is not to be found only in the contemporary, but also in reinterpreting the historical collection. This is just not only happening in our museum, but also for example with Ann Demeester at the Frans Hals Museum, or with Alexandra Gaba-Van Dongen at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen. It is the spirit of our time.

.jpg)

The Tropenmuseum, in Amsterdam, now part of the National Museum of World Cultures

LV. Tell me a bit about your parcours, how did you become a specialist in contemporary art from the non-western world?

AB. How did I end up in that field? I didn’t. When I studied art history, you could not study art from a global perspective. The canon I was taught was not precisely the Western canon, but rather the postmodern deconstruction of that canon. I entered the contemporary art world through Witte de With. It was the retrospective of Hélio Oiticica [Brazil, 1937-80] that made me apply for an internship there.

After working there for 6 years, I became course director of the Piet Zwart Institute, in Rotterdam. It was quite international (although not global). We had students from the Netherlands, Serbia, Lebanon, New Zealand… Then, I noticed that many artists really engaged with notions of culture, alienation, language and belonging.

When the first possibility ever to apply for a position related to contemporary art at the Tropenmuseum came up, I was interested. This museum already had a focus on contemporary art, through the work of Mirjam Shatanawi and Paul Faber.

I guess I am one of those people that learns by doing, instead of through academic training alone. Ultimately, all these experiences really influenced my way of working with Indonesian artists. I was coming from the way artists articulate their questions, not motivated by representation of non-western art per se.

LV. Now please explain to me your relation with contemporary art from Indonesia. What kind of artists have you brought to the collection? Do you have preferences in terms of media, or your work reflects conceptual interests instead? Can you say more about the work by Maryanto?

AB. When we talk about acquisitions, there must be a meaningful cross-connection with the existing museum collection. By adding contemporary art, you can change the historical collection and the way it is read. Maryanto’s work depicts landscapes destroyed by capitalism, and the large painting we acquired shows the devastated landscape of the Gold Mountain in West Papua.

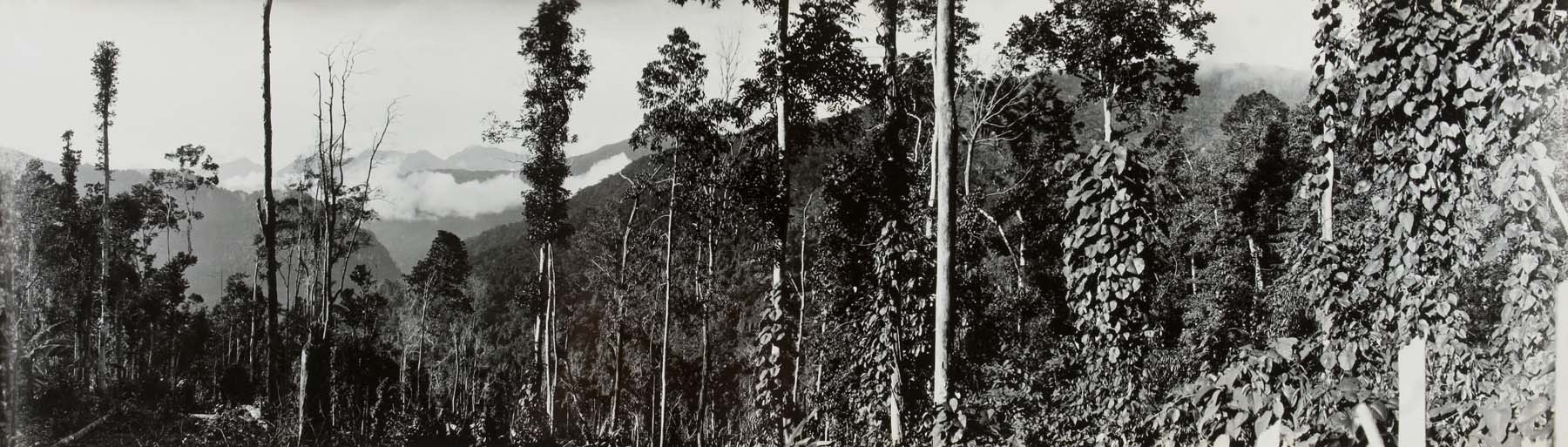

View of Papua gardens and the Ngga Nggulumbulu mountain. Photo made during the Dutch-American expedition to New Guinea (now West Papua), 1926. Collection National Museum of World Cultures, TM-60041364

There are two connections with the collection of the National Museum. Our photo archive contains extensive visual documentation of the various expeditions Dutch anthropologists and geologists, with military support, launched in Papua New Guinea in the early 20th century. They charted the area, extracted information, and in 1936 also reported the location of the ‘ore mountain’. Interestingly, Dutch colonial companies actually did not mine the area themselves. But when West Papua was handed over to the Indonesian government in 1963, this was the first site the New Order regime offered up for exploitation by multinationals, thanks to the information the Dutch made available. So one could say that in these photographs, we can see the beginning of the scramble for this region and the origins of a long history of exploitation. Maryanto’s painting is a graphic evocation of the outcome of that history.

.jpg)

Maryanto, Tales of the Gold Mountain, 2012, collection National Museum of World Cultures

LV. How would you then present this artwork in an exhibition?

AB. I think the beauty of an artwork as powerful as Maryanto’s is that it can establish a visual dialogue. If you present his painting next to the historical photographs, these are cast into a new light. A nice formal touch in this case is that both the historical photographs and Maryanto’s painting are in black-and-white.

L.J. Eland, Mountain Lake, 1915-20, collection National Museum of World Cultures, TM-2556-10

A similar dialogue is possible with another part of our collection: the ‘beautiful Indies’ genre paintings. These are idealised, paradise-like Indonesian landscapes, popular with the Dutch in a time when these lands and their people were actually in the grasp of colonial rule and industry. Maryanto sees his own ruined landscapes as a response to this genre and the histories entwined with it. In our museum, we can make that dialogue visible. It is a good example of an artwork that starts changing the meaning of the collection – a catalyst. There is a living dialogue going on.

LV. You have been recently appointed as Artistic Director of TENT in Rotterdam. Can you tell me what this new position holds in relation to your prior activity? What are your future interests in terms of contemporary art from the region, now that you are working for TENT?

AB. In many ways, TENT is very different from the museum context and mission. It is a center for contemporary art, focused on Rotterdam artists and taking the city of Rotterdam as a backdrop and stage. At the same time, Rotterdam has a very diverse community and can be seen as a crossroad of multiple cultural and historical influences. I’m interested in the ways in which a specific place like Rotterdam is connected with the larger global context. And I recognize an interest in such connections in the work of many artists. In their artistic efforts to make sense of the world we live in today many of them, like Maryanto or Jompet Kuswidananto who I also worked with at the Tropenmuseum, look at histories that have defined the present in large-scale economic or political ways, but sometimes also in a very personal and intimate sense, through family histories for example. It’s because of this shared interest that I’m confident that an engagement with Indonesian history and with Indonesian artists will find its way into the programme of TENT.

It is fascinating to understand the manner in which new curatorial strategies unfold today. The activity of Anke Bangma allows an understanding of those aspects that most commonly do not reach the public sphere but define the way museums currently operate.

© Leonor Veiga and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Leonor Veiga and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

.jpg)

.jpg)

0 Comments