Antigone in Kinshasa

The documentary Les fantômes de Lovanium commemorates the 1969 and 1971 student revolts against Mobutu. While Congolese painter Sapin Makengele visualizes the tragedy that took place, students and other bystanders start to share their stories. Through their stories, the spirit of Antigone emerges.

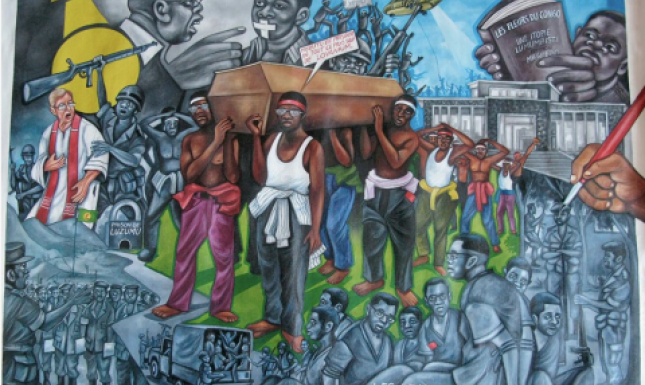

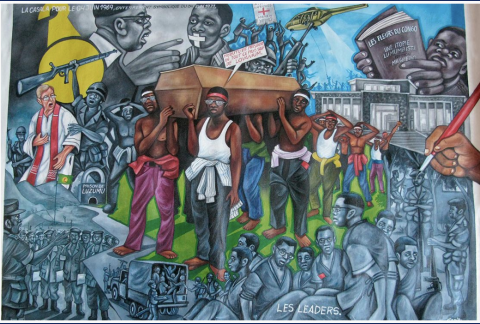

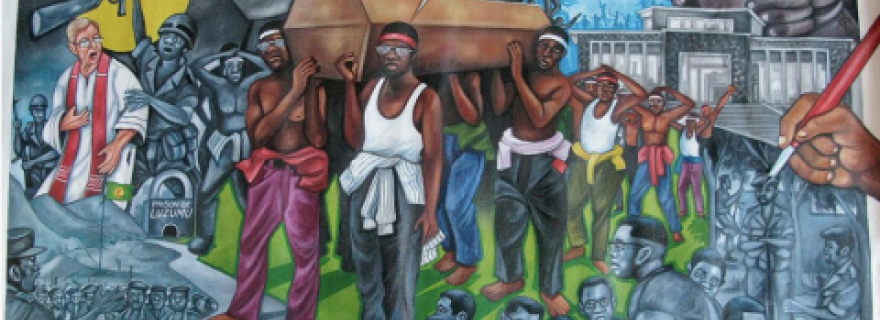

The documentary Les fantômes de Lovanium (2013) is the result of a collaboration between the Belgian filmmaker Cécile Michel and the Congolese painter Sapin Makengele in 2010 and 2011. It is especially interesting to me because of the ways it references Antigone, both explicitly and implicitly. The film shows Makengele working on a painting on the campus of the University of Kinshasa, which during colonial times was known as Lovanium, after the Latin for the Belgian city of Leuven. Lovanium was the first university in the Belgian Congo, founded in 1954. Makengele’s canvas is strapped to a tree and as the documentary progresses, it becomes clear what the painting is meant to represent: the student revolts of 1969 and 1971, when students protested against Mobutu. At least 38 of them were killed and thrown into a mass grave and 34 student leaders were arrested. Two years later, when Mobotu refused to hold a commemoration for those who had been killed (but did ask the nation to mourn his dead mother), another protest followed and a group of students was imprisoned.

The phantoms of the title, then, are many. Not only the students whose bodies were never properly buried and who could therefore never be properly mourned (the resonances with Antigone are clear here), but also the legacy of Belgian colonialism and, more specifically, the assassination of Patrice Lumumba who posthumously became an important inspiration for the student movement in Congo. And of course, the thing about phantoms is that they manifest themselves in the present. For the students who gather around Makengele’s painting, the past depicted holds painful resonances. And so, a reference to Mobutu in the painting evokes a telling response by one student: “You should update it,” he tells the painter, “You should write Kabila’s name instead, that would be powerful”. Another student asks Makengele: “Shouldn’t you talk about this year’s bodies at the campus as well?.…[They] disappeared too! Don’t forget to mention that”. Just as Antigone’s incomplete mourning of her father is repeated in that of her brother, so does the incomplete mourning of the murdered students of ’69 echo in the present of the Congolese students gathering around the painting.

In essence, the main character in this documentary is a painting from which the story of oppression slowly unfolds. The painting evokes the memories and stories of previous generations, and incites debate about the political present. Made at the exact spot where the massacre took place, the painting also bears witness to the tragedy. Through the painting the spectres of the past, also those that breathe resistance, are able to manifest themselves in the present. So when one of the students regretfully asks: “where did this spirit of students go? Why is it no longer there today?”, another quickly responds: “they are still alive”. This response reminds me of a few lines from Femi Osofisan’s Tegonni: an African Antigone, a play from 1994 about a Yoruba princess fighting against oppression. “Many tyrants will still arise,” it says, “furious to inscribe their nightmares and their horrors on the patient face of history….But so will Antigone! Wherever the call for freedom is heard”! It is as if through the painting, Antigone rises in the specific context of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The painting performs an act of remembrance and resistance. Depicting a traumatic event which in the political present is not openly talked about, it visualises what remained invisible, unspoken, undocumented. In a context where a functional national archive is lacking, storytelling becomes hugely important and this is exactly what the painting facilitates. Students, professors market women and children all gather around and together bear witness to the past depicted on the canvas in front of them. It is as if the painting enables the public mourning refused by the state. In this sense too, the spectre of Antigone becomes manifest.

The documentary is about the political power of art, not only because of the painting but also because of the Antigone performance which, a student informs us, took place the day before the protests: “We played Antigone by Anouilh,” he recollects, Antigone who “went to the frontline”. And later we see him with another student recite the trial scene: “You’re going to have me killed. And you call that being a king?” Antigone says to Congo’s Creon-figures Mobutu and Kabila. And when she laments that “Those who are not buried wander eternally and find no rest”, these lines are a powerful evocation of the phantoms of Lovanium.

Congo is not the only African context where the political relevance of Antigone resonates. Her popularity on African stages is striking. Playwrights such as Athol Fugard in South Africa, Femi Osofisan in Nigeria, and Sylvain Bemba in Congo, all emphasise Antigone as a political actor. Their interpretations reflect back on a tradition in which Antigone has very often been posited as a figure before, against, or beyond politics. And so does this documentary, which too forms part of Antigone’s reception history and further influences her political legacy. Antigone’s cultural migration has effects on Antigone’s status as a Western canonical figure. Forging a connection between Greek and Africa, Europe is affectively ‘circumvented’ and Greek tragedy is disconnected from the dominant culture that has claimed ownership of it. But then again: for those performing Antigone as a symbol of resistance against oppression, Antigone’s supposed cultural and historical origin was never the main concern. For them Antigone anticipates a future political order which goes well beyond Sophocles’ text. For the Congolese students performing Antigone the evening before their revolt in 1969, too, it was this activist potential that mattered most.

Political interpretations of Antigone often display an uneasy relation between stories of suffering and loss and emphatic messages of political change. It is as if the voices of those who suffer violence are in constant danger of being drowned out by the calls for resistance and revolution made on their behalf. This means that the emphasis on Antigone as revolutionary heroine is always in danger of obscuring her other identities: a woman unable to grieve, unable to move on. In the contexts of apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa, colonial and postcolonial Nigeria, and colonial and postcolonial Congo, where so many were never able to bury and mourn their loved ones, Antigone’s identity as a woman fighting for the right to mourn holds great relevance. What Antigone weeps for, writes Derrida, is less her father, perhaps, than her mourning, the mourning she has been deprived of. But most African Antigones never weep.

From this perspective, Phantoms of Lovanium strikes the difficult balance between an emphasis on Antigone as a symbol of activism, and on Antigone as a symbol of the losses this activism entails. On the one hand it shows how the spirit of revolt is rekindled and never disappeared to begin with, but on the other hand the documentary warns against a romanticization of activism and both represents and takes part in an unfinished process of mourning. One student laments: “Today, we’re merely surviving, not living. And when you lead a life like this, you’re not able to do anything else. What’s on your mind today, is that you’re hungry, so you don’t feel like claiming the rights of others.” Another claims: “So really we shouldn’t fear death, we might as well die instead of continuing this miserable life”.

And this is the tragedy presented here: of a generation of students who live in precarious conditions and face constant oppression. It remains distressing that the futures African Antigones help to construct have no place for them; that the change they instigate is always at the cost of their lives. In the concrete historical contexts of South Africa, Nigeria, Congo and other places in the world where people struggle against oppression, the greatest challenge remains to imagine Antigones who have a place in the futures they anticipate. Where, to be more concrete, the students who protested against Mobutu in 1969 and were killed because of it, had lived to see a changed reality.

Further reading:

Les fantômes de Lovanium (clip): vimeo.

© Astrid van Weyenberg and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Astrid van Weyenberg and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments