Archeologies of the Face

Do you own pictures of your face?

The question of whether resemblance with an image is enough for an individual to claim ownership rights over a photograph has arisen before. But it recently became a pressing matter for the social media giant, Facebook. Of the over 250 billion images that make up the site, which claims to be the largest photo-sharing service available, a significant portion are photographs of people with clearly visible faces. In May 2016, a group of individuals filed a class action suit against Facebook claiming that the site violated user privacy in the way it handled photographs uploaded by its members.

The dispute centers on the site's “Tag Suggestions,” a program only made available in the U.S. that allows users to type in the name of a person on a photo and thereby create a link with that person's profile page. The plaintiffs allege that the site does not warn users that the program generates, collects and stores information on the basis of these photos. Specifically, their complaint regards Facebook's use of “state-of-the-art facial recognition technology” to extract information regarding the identity of people on the photo. Beyond linking profile pages, the data generated by photographs extend to something called “biometric identifiers,” which, to quote the case file are “digital representations or 'templates' of people faces based on the geometric relationship of facial features unique to each individual, 'like the distance between [a person's] eyes, nose and ears.” Essentially, Facebook's program uses algorithms to turn images of faces into what has recently come be known as “face prints,” or facial geometries. Unlike fingerprints, or retina, iris or voice scans, the photograph is not currently considered a biometric identifier by the Illinois Biometric Information Privacy Act. In order to claim ownership over photos of their face, plaintiffs in the lawsuit against Facebook have to argue that a photograph of a face contains confidential information. According to this argument, collecting biometric identifiers from photographs is as illegal as, for instance, a merchant storing social security or credit card numbers without their customer's consent. And unlike the line numbers on a card that you can simply replace with a new one, once you're facial “identifier” is out, who is going to make you a new one?

The prisonhouse of identity

Zach Blas. Face Cage 4, endurance performance with Paul Mpagi Sepuya (2016)

There are few things we hold more dear than our anonymity. This is arguably what makes the case against Facebook so persuasive. If your name appeared everywhere your face went, most likely you would be keeping it in a jar by the door. This is the brunt of the argument made by a coalition of civil rights, privacy transparency groups and the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) that has been monitoring government collection of facial biometrics since it gained knowledge of proposals like the British Police planning to build a “national mugshot database” (2006), the Federal Air Marshals “surreptitiously photograph[ing] travelers” (2007) or the Interpol proposing a “worldwide facial recognition system” at border control (2008). It does not take much alacrity to imagine the direct impact on acts of dissent and civil disobedience by such plans for massive deployment of facial recognition devices. Photos are like fingerprints, one lawyer has argued. Just because you own a bar does not mean you can pull DNA off used pint glasses. The idea of a legible face gets us where we are most vulnerable.

Prison reform and typicality

Part of this sense of exposure has to do with our belief that our face is unique to us. People tend not to question that their face contains attributes that differentiate their features from that of others. But this assumption that our face is rightfully “ours” is not obvious. Faces have not always been conceived as the property of their “bearers.” In fact, one does not have to reach far into the history of photography to come up with suggestions to the contrary. One such example is the coincidence noted by historians between the dissemination of photographic portraiture with the emergence of criminological systems.

Allan Sekula has investigated the importance of “mutual comparison” in the strategies adopted by police investigators. Over a century before the British were considering a national mugshot database, Eliza Farnham, matron of a women's prison at Sing Sing New York, commissioned the daguerrotypist Matthew Brady to document inmates in two prisons for her criminological study, Rationale of Crime, and its Appropriate Treatment (1846).

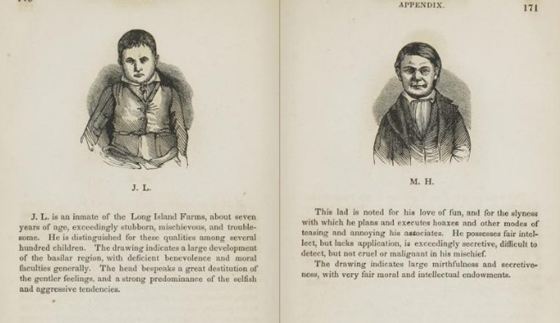

Farnham, Eliza W., Rationale of Crime, and Its Appropriate Treatment: Being a Treatise on Criminal Jurisprudence Considered in Relation to Cerebral Organization (New York: D.Appleton And Company, 1846), 170-171

Important to Farnham was to establish the notion that certain criminals could be reformed, and for this purpose, she ordered the drawings of Brady's mugshots along the lines of a “striking contrast.” With the face of the dour and cruel on one side and the temperate on the other, a differential regime governs interpretation of each subject in Farnham's collection. These faces only become legible within a system of other faces. Prudence cannot exist without impulsiveness, the idiot without the savant.

The face of the criminal does not make sense on its own. Before the criminal can be identified, they need to discovered in a social body. To the English statistician Francis Galton (1822-1911), the characteristics of a criminal were not visible from a mere photograph of their face. Rather, the criminal biometric needed “extracting” from a face, a process for which he devised an array of mechanisms.

Galton, Francis, ‘Composite Portraits’, Nature, 1878, 97–100

Mutual comparison was key to the demonstration Galton proposed to Inspectors of Prisons. Taking a given number of photographs, he suggested that a photo-sensitive plate be exposed to their negatives one after another. Given the superimposition, the outlines of the final image were “sharpest and darkest” at the points that are shared between individual specimens. In this manner, the “averaged figure” or “type” of criminal can be made visible at the direct expense of the individual. The entity to which this “composite portrait” belonged was distributed across other bodies. What the biometric yields is a system of types. To twist Sekula's words, the promise of the portrait is not the individual but the filing cabinet.

Composite portraits showing "features common among men convicted of crimes of violence," by Francis Galton, with original photographs. University College London

Conclusion: Effacement

The face possesses a certain stature in the history of media, as it often accompanies the emergence of “new” media. Many an inventor has hoped for fame and success by arguing that their contraption could reveal or unveil something new about the human soul. One might even wonder if we have not become more enigmatic and “profound” because of such claims. In suggesting that the senses are “expanded” through media, the expressivity of the human face is often conflated with the kind of awe and wonder that historians have described as a technology's novelty effect. Part of a larger project, this series examines select cases in which the face prompted and contextualized a given technology's ability to produce information. In each case, the technology offers up data of which the face provides analysis. In each case, the face occupies the threshold between raw and intelligible data. Its legibility constitutes information. But whether this information has anything to do with original “bearer” of the face is debatable. It is the purpose of this series to suggest that the face is not a stable entity, the stuff of skin and bone that we carry around on our shoulders. Rather, the face is an invention. Or more properly speaking, the face is the condition for a given technique to declare itself an invention. As such, the face constitutes one of the most elusive aspects of modern visual culture and technology.

Further reading

Stern, Madeleine B., ‘Mathew B . Brady and the Rationale of Crime A Discovery in Daguerreotypes’, The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress, 31 (1974), 126–35.

© Eszter Polonyi and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Eszter Polonyi and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments