Brunelleschi and the Dome of Florence: How to Make a City Proud

The cultural hero displays a fixed set of characteristics: brilliance of mind, work ethos, and a talent no one else possesses. These qualities explain how Filippo Brunelleschi could create one of Tuscany’s greatest landmarks, 600 years ago.

This blog is part of the "Roaring Twenties" series.

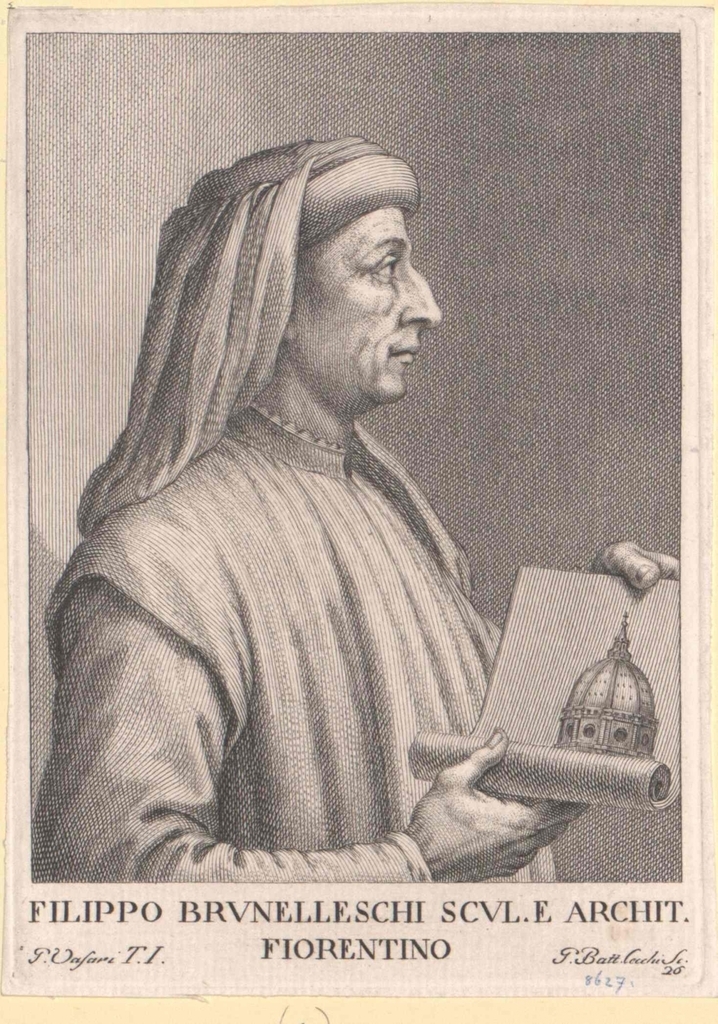

This year, Florence celebrates the 600th anniversary of the dome of the city cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore. Why celebrate the anniversary of a dome? Well, this specific cupola was thought to be an impossible task at the time of its construction, which lasted from 1419/1420 to 1436. Moreover, the man who designed it was a hero, not in the least because he convinced his fellow citizens he could do it simply by cracking an egg. This man was Filippo Brunelleschi, goldsmith, clockmaker, sculptor, (re)inventor of the art of perspective, antiquarian, architect—in one word, as many tend to call him, a Genius.

I’m not an architect or an art historian, but two things interest me. Why was this dome so special that it needs to be celebrated this year? And why is Brunelleschi’s name tied so closely to the building of the cupola, while there were many people involved over the years, and it wasn’t even completely finished when he died in 1446?

The Santa Maria del Fiore is not just a church. Everybody who has been to Florence will be able to visualize easily the Florentine cathedral rising out above the city and visible from the hills of the countryside. The construction of the church began around the end of the thirteenth century and took over almost two centuries to be completed. When it was finished, according to the famous architect Leon Battista Alberti, all villages in Tuscany fell in its shadow. Slightly exaggerated, yes, but it shows the political and social value that the cathedral had (and has) for the region. From the thirteenth to sixteenth century—the ‘roaring’ Renaissance—the Santa Maria del Fiore symbolizes on the one hand Florence’s political dominance over the cities in Tuscany, and on the other bears proof of her wealth and her status as a liberal and artistic bulwark.

Architectural rhetoric also speaks to us from the plan of the cathedral. The different parts of the magnificent church symbolize the parts of Florentine society. According to the art historian Howard Saalman, the octagonal center part of the church represents the Republic of Florence, and its “arms” or the three apses the Church (east), the Guelfs (south), and the guilds (north), which had turned Florence into a merchant city par excellence. The nave and the aisles, then, could host 30.000 citizens and contadini, making it the fourth biggest church in the world after Saint Peter’s in Rome, Saint Paul’s in London, and the Milan cathedral. The dome with the lantern on top makes the cathedral over 110 meters high.

This is all pretty impressive, but the Florentine citizens were even more impressed by Brunelleschi’s ability to both build a humungous octagonal dome in brick, and do it without any preliminary or lasting internal support system. See, this is what I like about Brunelleschi: according to his biographers, his architectural knowledge was self-taught on the basis of a long sojourn in Rome (together with Donatello!), where he studied the classical temples and the dome of the Pantheon. His sense of proportion and symmetry, and the belief that it was possible to build a dome that was self-supportive derived from this study trip. Many an academic should be inspired by Brunelleschi, who knew how to do proper study and on that ground was confident enough to embark on an unprecedented and daring project, discovering the necessary details along the way.

That Brunelleschi was extremely confident becomes clear from the biographies of one of his pupils Antonio Manetti and the later Giorgio Vasari. One more prerequisite for becoming a cultural hero: contemporaries and later admirers should write your biography and proclaim you a genius.

Now, Brunelleschi played a clever game. The commissioners tasked with the construction of the dome were frantically searching for experts to vault it. They appealed to Brunelleschi’s expertise, which was already famous. Brunelleschi, instead of demanding the job, which paid good money, offered them his tantalizing but highly efficient plan (i.e. building without internal support system). Pretending not to care, he went back to his ‘own’ business and returned to Rome, where he in fact secretly studied more domes. Vasari gives us an impression of his cunning rhetoric, which may not be an truthful representation of the real Brunelleschi but is a telling interpretation of the man-as-legend:

Conditional sentence constructions (“if the dome could be rounded”, “if I were commissioned to do it”) here alternate with phrases like “I am confident”, “I would courageously and resolutely discover a way”. On the one hand, Vasari's Brunelleschi instils in the commission the belief that the construction of the dome is a difficult task. He also alludes to precedents in classical architecture which were rediscovered by him and little known among his contemporaries. On the other hand, he makes them believe that if somebody could do it, it would be him. What’s more, it would be him alone, since, as he deviously remarks, he cannot help if the project is not his. This is the privilege of the expert: by cleverly playing on your audience’s ignorance, you can convince them that nobody knows as much as you do. Conclusion: you are the only person up to the task, which means they desperately need you. And indeed, Brunelleschi’s braggadocio got him the job.

In his TED-talk, fan and filmmaker David Battistella proposes that Brunelleschi was the original Renaissance man, the predecessor of Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the like. I don’t know about that, but what I do know, as a classicist, is that Brunelleschi and his dome both acquired fame through the force of their rhetoric. The Santa Maria del Fiore uniquely embodies the power of Florence which, literally and figuratively, rose to the skies. The figure of Brunelleschi represents the unique strength of the intellectual with a vision, who knew how to promote his expertise and to do what nobody else thought possible. He talked himself into the history of Florence; Florence in her turn could long after flaunt his genius as part of her reputation—which is exactly what is happening this year, 600 years after Brunelleschi cracked his egg.

This video, by courtesy of National Geographic, explains why the dome of the Florence cathedral is such an extraordinary achievement.Reading

Bondanella, J.C. & Bondanella, P.E. (transl.). 1998. Giorgio Vasari. The Lives of the Artists, Oxford.

Fanelli, G. & Fanella, M. 2004. Die Kuppel Brunelleschis: Geschichte und Zukunft eines großen Bauwerks, Florence.

Saalman, H. 1980. Filippo Brunelleschi. The Cupola of Santa Maria del Fiore, London.

Saalman, H., Engass. C. (eds., transl.). 1970. Antonio di Tuccio Manetti. The life of Brunelleschi, University Park (PA).

© Leanne Jansen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Leanne Jansen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments