Curse and Comfort: Classics and the First World War

Can ancient texts be relatable to those who have just gone through the traumatic experience of armed combat? Well, according to some of the poets who composed their works during the First World War they can – while others suggest that they really can’t.

At the very beginning of the British Museum’s current exhibition on the myth and reality of the Trojan War, visitors are met with an announcement by the curators: “Troy: myth and reality tells a story about war. It includes depictions and discussions of violence and other aspects of conflict.” While the exhibition received praise for its handling of the archaeological, historical and artistic material, some reviewers were surprised by these initial words of caution, arguing that Troy is so closely connected to war and violence, that the warning was rendered “pointless” by the general public’s familiarity with the subject. Other reporters, however, came to see its use over the course of their visit, and explained to their readers that, while being familiar with the narrative of Homer’s Iliad, they had not realised the extent of the violence that would be on display.

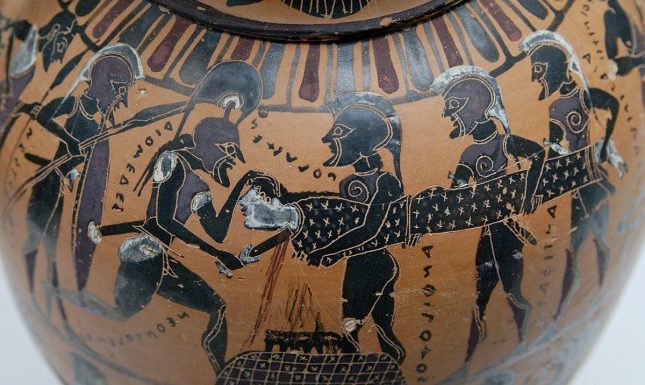

Vase depicting the sacrifice of the Trojan princess Polyxena, which is part of the Troy exhibition, ca. 570-550 BCE (British Museum, London).

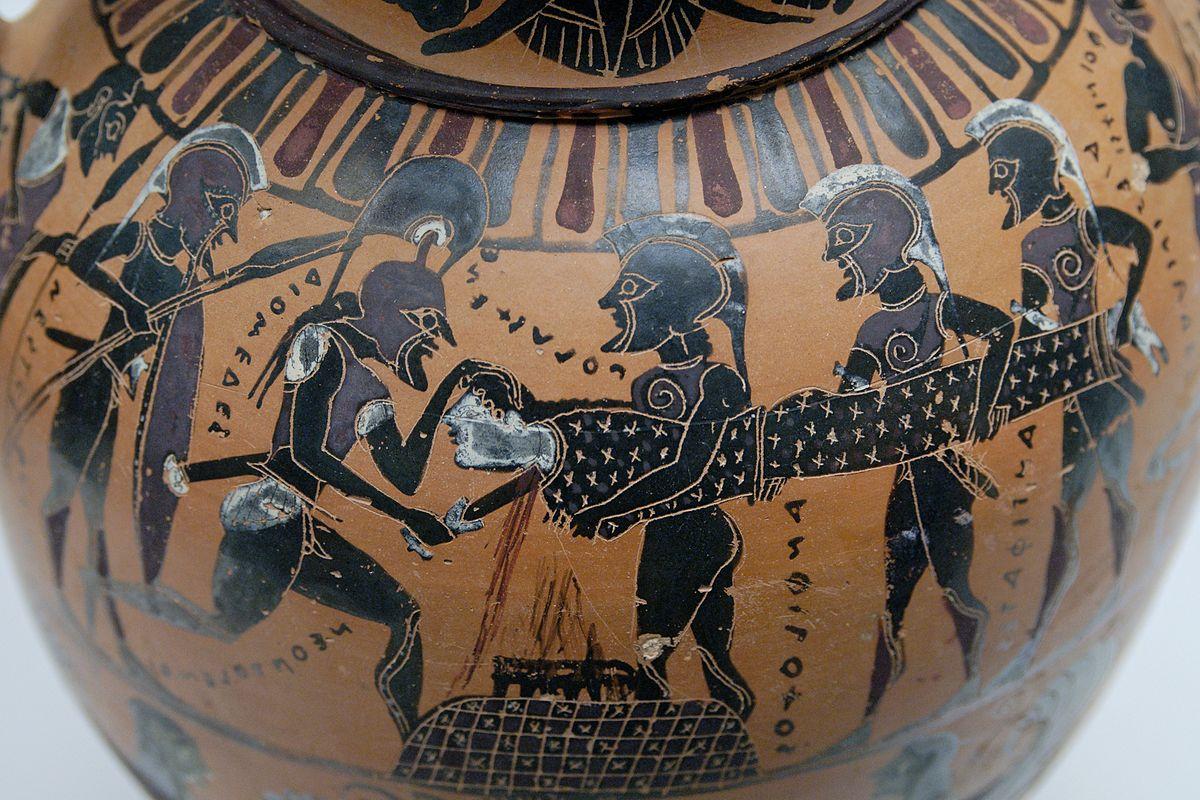

Throughout the exhibition, it is easy to understand why the connection between the titular myth and reality of violence in the Trojan War has proved to be somewhat more contentious than may at first seem apparent: while the creators of ancient artefacts frequently offer striking, and sometimes graphic, visual and written depictions of the horrors of war, their portrayals are usually less immediate and realistic than those to which a modern audience has grown accustomed – especially without the vividly coloured paint with which some objects would originally have been covered. Reading Homer’s description of the Greek hero Ajax cracking open his Trojan opponent’s skull with a rock, as gruesome as it may be, is a noticeably different experience than, say, the recent film 1917, which even at a distance of more than 100 years manages to convey the experiences of soldiers in the First World War with startling and horrifying immediacy. However, this does not mean that the narratives about ancient military conflicts are completely distinct from modern, lived experiences of violence. As professor of Greek Ineke Sluiter discussed during the first LUCAS lecture on 28 November 2019, those who have experienced active combat often recognise their own experiences in stories about Greek and Roman warriors – and have done so throughout history, even when the reality of war had come to look radically different.

‘Gassed’ by John Singer Sargent, 1919 (Imperial War Museum, London).

This sense of recognition is perhaps nowhere more clearly visible than a poem that has become known as Achilles in the Trench (1915). Its author, Patrick Shaw-Stewart, had a thorough background in classical literature and, like many of his contemporaries, made elaborate use of this knowledge in his work.[1] For Shaw-Stewart, the many stories surrounding the Trojan War made for an especially poignant comparison to his own experiences, since he was initially deployed not to Flanders – by far the period’s most famous battlefield – but during the British campaign to Gallipoli. The Gallipoli peninsula, considered to be of great strategic importance for the conflict against the Ottoman Empire at the war’s eastern front, was located approximately 60 kilometres from the ruins of ancient Troy, and the legendary history of the region echoes through every line of Shaw-Stewart’s poem:

Audio version of Shaw-Stewart’s Achilles in the Trench, read by Jonathan Jones as part of his Great War Verse project. A written version may be found here.

In the Greek hero Achilles, Shaw-Stewart sees a fellow warrior. Rather than being a figure to be emulated and envied, Achilles appears both as a frightening example of death in battle, and as a potential source of comfort and support, who understands what the poet is going through and can give him courage with his battle cry. The comparison, however, goes even further. Through an impressive intertextual play on words, Shaw-Stewart suggests that both wars were, ultimately, both lethal and pointless. In the poem’s third stanza, he evokes the Greek poet Aeschylus’ play Agamemnon, in which the chorus laments that no-one has ever had a more suitable name than Helen, over whom the war was fought. She, after all, proved to be helenas, helandros and heleptolis – a destroyer of ships, men and cities. The connection between Shaw-Stewart’s fatal second Helen and the destruction he himself experienced is furthermore reinforced by the rhyming words shells and hells – for all its new weaponry, he seems to say, this conflict was ultimately just as explosive, just as lethal, and just as pointless, as the war over the Spartan queen.

‘The Harvest of Battle’ by Christopher R.W. Nevinson, 1919 (Imperial War Museum, London).

While Shaw-Stewart seems to have found some comfort in Homer’s Iliad, not all poets of the period saw things the same way. Throughout Europe, the war had a profound effect on arts and literature, and its thoroughly modern horrors (like flame throwers, machine guns and especially poisoned gas) led some to view classical tradition as unrecognizable at best, and misleading at worst. Some important hints of this development may be found in the works of Wilfred Owen, who has become perhaps the most famous poet of the period. While Owen saw knowledge of Greek and Latin as essential for his work,[2] and did indeed reference classical themes in a number of his poems, his admiration was hardly unambiguous. In 1914, he describes ancient Greece and Rome as a long-gone spring and summer of poetry that has since made way for winter. What’s more, in a preface to his work composed shortly before his death, he appears to reject the programmatic opening lines of Vergil’s Aeneid by stating that his work is “not about heroes […] nor is it about deeds or lands, nor anything about glory, honour, dominion or power” – all important themes for classical heroic epics – but rather about “the pity of War”.

Audio version of Owen’s Dulce et Decorum Est, read by Christopher Eccleson. A written version may be found here.

Most famous, however, is Owen’s reference to Horace’s Odes in his poem Dulce et Decorum Est. The poem deals with a gas attack and its immediate aftermath, and it is the contrast between Owen’s dark, almost enraged descriptions and the Latin citation in the final lines that lends the work a large part of its impact. In its original version, the phrase “it is sweet and honourable to die for one’s country” was used to encourage the reader to die a hero rather than to live a coward. In Owen’s hands, however, the phrase becomes deeply cynical, an indictment of the hollow rhetoric that led young men into war, but ultimately betrayed them. Rather than being a source of comfort and recognition, classical tradition has become – in Owen’s words – “the old Lie,” and as such it might rightly require a warning label – but for an entirely different reason.

Notes

[1] For an elaborate study on the importance of the classical tradition in the works of British War Poets of all backgrounds, see the seminal study by Elizabeth Vandiver, Stand in the Trench, Achilles: Classical Receptions in British Poetry of the Great War (Oxford, 2010).

[2] See Vandiver (2010), 118-119. See ibidem 129 for the argument that Owen’s knowledge of Latin was lacking at best, and that some of his more famous references to classical sources may have been due to cultural osmosis rather than direct knowledge.

Banner Image: ‘Landscape with Trench and Barbed Wire’ by George Spencer Hoffman, 1915 (Imperial War Museum, London).

© Renske Janssen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Renske Janssen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments