Decolonising Book History

On 15 June of this year, I participated in a roundtable on Decolonising Book History. In this blog, I share my experience and some of the points we discussed.

The discussion on discrimination is not new. Lately, the public debate has centred on systemic police violence towards blacks and people of colour. Scholars and scientists have also taken part in these and similar discussions, not only as experts but also as perpetrators and victims.

At this year’s online SHARP conference (The Society for the History of Authorship, Reading and Publishing), I was fortunate to join a conversation on the challenges and steps for opening up our discipline to new horizons.

Aren’t all scholars equal?

There are many on-going discussions on how to decolonise academia. Brighter minds have explained that better (for example here, here, and here), so in this post I will just give a very brief background introduction.

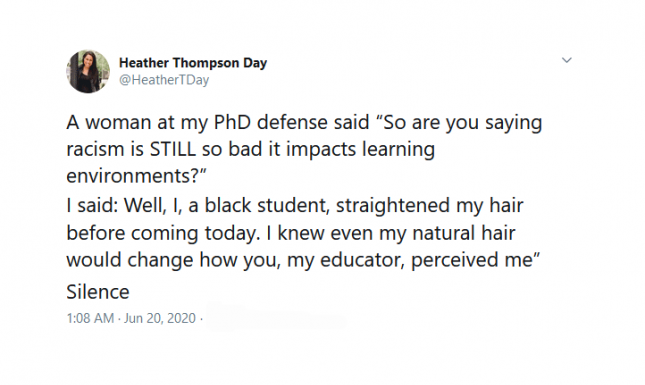

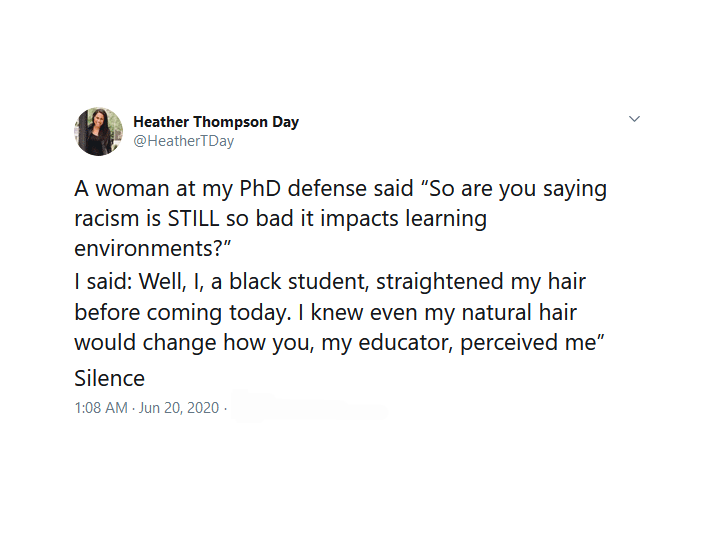

Academia prides itself on upholding values such as intellectual rigour and objectivity, which form the basis for the quality of our work as scholars. However, academia does not exist in a vacuum, and consequently it reflects and perpetrates the structures outside of a university’s wall. There are as many inequalities inside as outside. In fact, given that the structures that allow or limit individuals to follow an academic career are a product of society. the racial and gender differences may be even starker.

The effects of these inequalities are many. Although examples can be found in other disciplines too, the focus of this post lies in my own field: book history. One of the main issues concerns who gets recognised as a scholar and as having the authority/experience of one. This determines who gets a grant or tenure, is invited to conferences, cited, and published.

Another issue is which stories are told, who gets to tell them, and in which language. For example, the story of print is often told as if it only existed in Europe and in the United States of America. When other areas are covered, they tend to be explained through the lens of an outsider while the local/regional experts are not considered.

These and other issues affect first and foremost scholars from a non-white and/or non-Western background. As a result, the way in which research is carried out and how history is written is also affected: it is incomplete. Just as the inequalities in the wider society have given way to calls for reform, scholars in book history have also questioned the organisation of our discipline; what histories are not being told?

Starting the conversation

Last year, Dr. Melanie Ramdarshan Bold and Dr. Danielle Fuller called for a roundtable on decolonising Book History at the annual SHARP conference. Although they received many submissions, a diverse panel could not be put together. The organisers felt that having a discussion by a panel that was not diverse defeated the purpose and so they cancelled it. This year, I was overjoyed that my abstract was accepted and that the quota for a diverse panel had been met.

Before we move forward I must position myself on the issue of diversity. I am a woman of colour that was born in a non-Western country. My colour is a café con leche, and if the Sun goddess has not graced us in the Netherlands, it tends to be more leche con café. My ethnic background is mestiza (a problematic term by itself), which is the largest urban/power group in Mexico, and on a socio-economic level I belonged to one of the middle classes. Although there are various levels of discrimination in my home country, by no means have I suffered the worst of it. Sadly, us mestizos continue to exploit and marginalise the indigenous peoples of Mexico.

Since we had to move the gathering online, other scholars who had not submitted an abstract (because conferences fees and travelling are expensive), were able to join us. In the end, we enjoyed a most magnificent formation: Marina Garone Gravier (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), Priya Joshi (Temple University), Jean Lee Cole (Loyola University Maryland), Kinohi Nishikawa (Princeton University), Derrick R. Spires (Cornell University), and yours truly chaired by Dr. Ramdarshan Bold.

How to decolonise in an hour

The topic is immense, and can hardly be covered in one roundtable. The goal was not to solve the many issues, but to reflect and start a discussion on which steps we as scholars can take in our practices and as members of university departments. To keep things manageable, we focused on what decolonisation means in our practices and how we can decentre our field.

The conversation was vigorous, and it was very rewarding to hear how researchers covering different aspects of book history approach the issue of decolonising. In general, most of us are trying to shift the focus away from traditional actors and objects. For example, studying the uses of print by marginalised peoples (slaves, minorities, women) or focusing on less “glamorous” printed objects such as broadsheets or comics.

Another point of discussion was the role of the archives in maintaining the status quo. According to Walter Benjamin, “there is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.”[1] In other words, archives are not objective/neutral collections and like all narratives they have been constructed in a particular way. For some participants, the way forward was to look outside the official archives, while for others the best strategy would be to turn those archives against themselves.

This subversive use of archives as well as focusing on subaltern subjects and different objects are some of the steps that can help to decolonise the curriculum. Another step is to question the narratives of splendour that are inevitably coupled with notions of civilisation and the book as a cultural object. This includes contextualising how certain printed works came to be and what their role was in the enslavement of other peoples.

It was also frustrating to hear how many obstacles there still are. Not only are BIPOC scholars a minority in academia, they also face apathy and hostility. Some of the economic and social structures that limit certain communities from taking part in scholarly endeavours reach beyond the resources of university departments; however, not beyond what we can do as citizens.

Other obstacles to open up conversation are perhaps ‘easier’ to tackle, for example by decentralisation. For example, not calling a monograph on the history of the book in Europe a “Global History of the Book” but situating it regionally. Europe is not the world. Another much needed step is to recognise the research being done in the global South and the limitations that these scholars face. And finally, journals and association boards must include scholars from diverse ethnic and regional backgrounds.

Our ethical duty

At the end, this all boil downs to our own ethics and values. If we claim that we are studying the history of print, manuscript, and reading we just cannot ignore histories outside of Europe/The West, nor can we ignore the role of print in colonial endeavours. The road is of course not simple, nor is there one single recipe. As Dr. Garone Gravier noted, it is good to also see what other disciplines are doing. We need to listen to other voices and bring them in. As the American feminist and writer Audre Lorde has said: “difference must be not merely tolerated, but seen as a fund of necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic.”[2]

If you would like to view the Book History Roundtable for yourself, click here.

Further reading

Bhambra, Gurminder K, Dalia Gebrial, and Kerem Nişancıoğlu. Decolonising the University. London: Pluto Press, 2018.

https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/25936

Antonelli, Alexandre. 'Director of science at Kew: it’s time to decolonise botanical collections,' The Conversation, June 19, 2020

https://theconversation.com/director-of-science-at-kew-its-time-to-decolonise-botanical-collections-141070

Khandwala, Anoushka. 'What Does It Mean to Decolonize Design?,' Eye on Design, June 5, 2019.

https://eyeondesign.aiga.org/what-does-it-mean-to-decolonize-design/

Appleton, Nayantara Sheoran. 'Do Not ‘Decolonize' . . . If You Are Not Decolonizing: Progressive Language and Planning Beyond a Hollow Academic Rebranding', Critical Ethnic Studies, February 4, 2019.

http://www.criticalethnicstudiesjournal.org/blog/2019/1/21/do-not-decolonize-if-you-are-not-decolonizing-alternate-language-to-navigate-desires-for-progressive-academia-6y5sg

Notes

[1] Benjamin, Walter. (1969) “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” In: Illuminations, Essays and Reflections, ed. Hannah Arendt & transl. Harry Zohn, Berlin: Schocken Books, 256.

[2] Lorde, Audre. (2007, repr. of 1984) “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” In: Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press,110-114. Print.

Credits for the banner image: Book Studies Allard Pierson Amsterdam, and El Comandante on Wikimedia Commons.

© Andrea Reyes Elizondo and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Andrea Reyes Elizondo and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments