Drawn to deviance: the deformed body exhibited

How and why is a body we see as ‘deformed’ able to arouse strong affective and aesthetic responses? Andries Hiskes explores how, where, and when a body is presented to us matters in how we experience it through a discussion of the film The Elephant Man.

For the past year, my research has mainly been focused on the concept of ‘deformity’. What initially drew me to this concept was the notion that when we experience a body as being ‘deformed’ or ‘disabled’, we do so in relation to a normative idea of the human body. The normative character of that idea mainly consists of our shared expectations of what a ‘normal’ body looks like: two arms and a pair of legs, for example. When a body deviates from this expectation, by having six fingers on one hand or by missing a limb, our attention is often attracted to this feature. ‘What does it mean?’ ‘How did that happen?’ ‘Were you born that way’?

Yet, when we think of what the ‘normal’ body looks like, one of the issues we encounter is that, while we could attempt to draw it or make a depiction, in actuality, bodily variance runs the gamut. No two bodies are exactly alike. What is simultaneously also clear, however, is that not all bodies attract the same amount of attention: what deviates often also captures our imagination, whether it is because we find it extraordinarily beautiful or disgustingly grotesque. As the array of questions in the previous paragraph show, one of the affordances of ‘deformity’, then, is that our curiosity is aroused and that to some extent, we are drawn to study it.

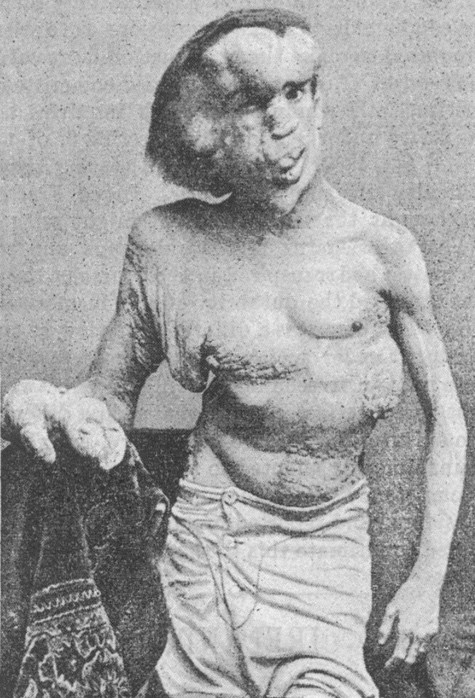

Img. 1. Joseph Merrick, 1889 (source: Wikipedia)

One of the case studies I used in my research is David Lynch’s film The Elephant Man (1980). Lynch’s film is a fictional portrayal of the life of Joseph Merrick, called John Merrick in the film, a man who’s severely deformed and living in 19th century London where he’s displayed in a freak show. My interest in the film grew as I began to notice how much of the film is concerned with the practices of exhibition: whenever Merrick’s body appears in the film, it is in some way always in the form of a presentation.

The film opens with the freak show exhibiting cardboard cut-outs advertising ‘The Elephant Man’, but Merrick himself remains hidden from view. Frederick Treves (played by Anthony Hopkins) a physician at London Hospital, is interested in seeing the Elephant Man and arranges for a private showing. As the performance starts, Merrick’s ringmaster, mr. Bytes, theatrically introduces Merrick to Treves. Bytes calls Merrick half man, half elephant, as he opens the curtains behind which Merrick sits. Although we, as an audience, briefly get to see Merrick, the focus of the scene is actually on Treves—more specifically a 27 second zoom-in on his face as he stares at Merrick, unblinking.

Img. 2. Treves seeing Merrick for the first time. David Lynch's The Elephant Man 1980

Treves takes Merrick to London Hospital in order to examine him, but also in order to display Merrick to his colleagues. Again, we as an audience don’t get to see much of Merrick, as the camera’s angle is such that we can only see a distorted shadow behind a curtain. In his presentation, Treves refers to Merrick as the most ‘perverted and degraded version of a human being’ he’s ever come across before he starts to elaborate what is medically the case with Merrick’s body.

What is interesting in these two scenes of exhibition is how they are alike and how they differ. What is similar in both scenes is that Merrick is reduced to being solely an object of display—robbed of agency of any kind before his audience, only there for the rest to gaze upon his body. But Treves’ role meanwhile, has markedly shifted: from that of being an audience while attending the freak show, to being an exhibitioner at the hospital.

Img. 3. Merrick being displayed by Treves at London Hospital. David Lynch's The Elephant Man 1980

Treves eventually develops a closer relationship to Merrick as he’s allowed to stay in London Hospital. Initially deemed to be illiterate and mentally handicapped, Merrick instead shows himself to be sensitive and eloquent. This eventually culminates in Treves inviting Merrick over to his home for tea where Treves’ wife, Ann, receives him. Merrick relates his past to Ann, and wonders whether his mother (who seems to have abandoned him as an infant) could love him if she could see him now in their company, causing Ann to break down in tears.

Img. 4. Merrick and Treves’ wife, Ann. David Lynch's The Elephant Man 1980

As opposed to the other two cultural spaces of the freak show and the hospital, what is markedly different in the space of the home is that here, Merrick has become a guest rather than solely an object of exhibition.

One of the things that The Elephant Man makes me question is to what extent the deformed body needs to ‘prove itself’ as a social agent. That is to say, it was only until Merrick showed himself to be literate and speech-endowed that the way he is treated by his surroundings shifts. Secondly, the film investigates how aesthetic responses such as a shock and wonder are not separated from professional settings like a medical presentation; they often overlap and coalesce in ways that make it difficult for us to see how aesthetic judgements often casually become a part of seemingly objective and professional presentations.

The Elephant Man allows us to reconsider the relationship between how we treat non-normative bodies that evoke strong responses in us. To strongly police the range of these responses seems to me to be both unfeasible and undesirable. Rather we should ask how, when, and where these responses lead to the silencing of the body in question, where it is on display only and when and where it is allowed to speak and act freely. Instead of desiring to regulate our aesthetic judgements, we could take them as a point of departure for how they situate and shape our engagements with bodies that deviate from a experienced norm; how can we move from the often paralyzing gesture of the stare to the production of a dialogue? To reconsider our own aesthetic responses to non-normative bodies is not an easy task, but it is one, I argue, that is worth our efforts to explore.

© Andries Hiskes and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Andries Hiskes and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments