House of Industry – An Arsenal without its Researchers

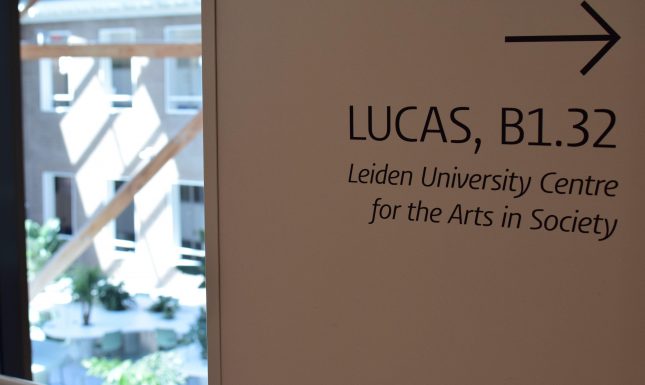

March 20th 2020 would have been a momentous day: the day that the LUCAS would move into its new location the Arsenaal. It had been a long process to bring all the members of the institute together—not just in mind but also in place. But history proved its bitter irony once again.

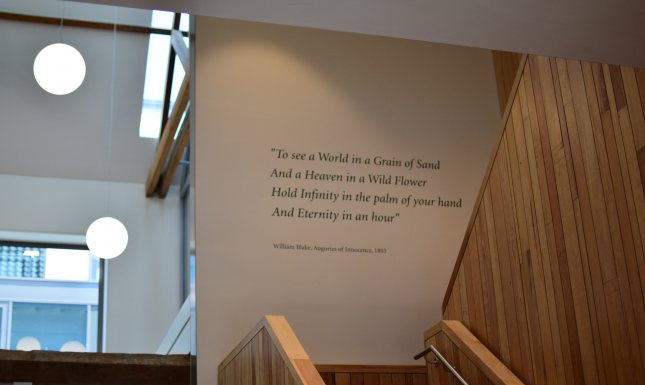

Right when all our academic belongings needed to be packed into moving boxes, the whole country had to pack up and go home due to the measures taken against the coronavirus. Friday the 13th, indeed. Although the Arsenaal has been refurbished and drastically restyled, and although our belongings have already been moved there, us researchers have not been able to enjoy our new environment yet. The LUCAS MT granted the Leiden Arts in Society Blog editors special access to give you a (virtual) tour through our new workplace. In this blog, we share numerous photo’s of the Arsenaal’s interior attesting of the surreal atmosphere our non-move has caused. Since we remain researchers we also tried to make sense of this architectural situation with the help of some theoretical frameworks.

Beforehand we had suspected the place to have some elements of the uncanny, but it didn’t. For a place to feel uncanny, unheimlich, it—firstly—needs to have been inhabited by people. It is the removal of people that makes a place uncanny, not just the sheer absence of them. With the refurbishment of the Arsenaal, it seems that the students and employees formerly wandering her corridors have been erased. It is indeed a blank slate. The building now resembles an unfulfilled promise: the ‘building up’ of the renovation plans, the thrilling renovation itself and later the packing of boxes, the emptying of your desk and the book shelves—it was an energy never released. The boxes, scattering of chairs, and the hipster abundance of green hint at a glittering prospect of scientific endeavour in a sustainable, bright and 21st century building. However, the Arsenaal is now just inhabited by plants and it is merely gathering dust. Yet, the promise of reincarnation is just around the corner—the automatic doors giving the impression that someone else could be here.

With the Arsenaal not being able to fulfil its function just yet, it perhaps has some characteristics of Foucault’s heterotopia: a contradictory space, a place without place. In the time leading up to the move many of us shared serious reservations about the design of the building. The size of the (shared) offices, the amount (and length) of bookshelves were discussed. Probably it belonged to the initial hesitation and the anxious anticipation of having to come to terms with a new living space. Yet, the relocation of the LUCAS employees had a clear goal: to bring our researchers together not just in space but also in mind. Fostering the interdisciplinarity our institute possesses at its core, and stimulating the meeting of minds and ideas in the new LUCAS lounge or at one of the plenty coffee machines. In this regard, the MIT Building 20 experiment is a perfect example of the effectiveness of mixing researchers of different disciplines together.[1] It is ironic that since the move there has been (quite literally) no space for either testing our doubts or bringing our research together.

The very thing the Arsenaal was supposed to stimulate has been halted by the coronavirus. Our opportunity to define ourselves within the space we share—physically, but also socially—has been shelved like the books in our offices (for those who have actually unpacked). Further away than we ever were when still working in the Eyckhof and Huizinga, we are working from home, minimizing the contact that is so vital for doing research.

But to end these architectural musings on a positive note: the unfulfilled promise of the empty Arsenaal shows us the essential need for a communal place for LUCAS. The Arsenaal is not just a building, it should indeed be a “house of industry”, housing our researchers and granting the space for great ideas.

References

[1] MIT “Building 20” was a hodgepodge of researchers from very diverse research areas thrown into one building together. The combinations of people who could converse were “strange and wonderful”, which made Building 20 MIT's most productive and successful building ever (Harford, 2016: 80–88).

Further reading

Michel Foucault (1998). “Different Spaces”. In Faubion, James D. (ed.). Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology: Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984, v.2, New York, 175–185. [Transl. Des espaces autres.]

Peter Johnson’s website on the concept of heterotopia.

Tim Harford (2016). "Workplaces". In: Messy: How to be Creative and Resilient in a Tidy-minded World, London, 67–97.

© Leanne Jansen, Merel Oudshoorn, Liselore Tissen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Leanne Jansen, Merel Oudshoorn, Liselore Tissen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments