Forgetting Cicero

Is it possible to control the way you are remembered by posterity? What the politician and writer Cicero can teach us about processes of commemoration and canonization (an introduction).

Nicht Erinnern, sondern Vergessen ist der Grundmodus menschlichen und gesellschaftlichen Lebens.[1]

When I was in a bookshop in Berlin Hauptbahnhof last February, my eye was drawn to a German magazine about politics called Cicero. I picked it up eagerly, but was disappointed to discover that its contents had nothing to do with antiquity. The name ‘Cicero’, though it did in fact reflect the conservative outlook of the magazine, mainly served to give the magazine some cachet. What is old is authoritative, and recognisable for a wide group of people. Traditional concepts can be used to support modern points of view, especially when this tradition is considered to be ‘Classical’.

The homepage of the website ‘Cicero, Magazin für Politische Kultur’, which has even claimed the domain name Cicero! See: Cicero.de

The classical author this magazine had chosen for their title is the famous Roman orator and writer Marcus Tullius Cicero. He lived during the last, tumultuous years of the Roman Republic, and quite soon after his death in 43 BC became part of the historical and literary canon. Consequently, he has been a primary example for politicians, scholars and school teachers for over 2000 years. Could he ever have dreamed his life and work would have such an effect on history?

Well, he did dream about it. A lot. And he wrote an awful lot about it, too. No classical author was as concerned with his legacy as Cicero. During his life he asked one of his friends, Lucceius, to write him a monograph about a conspiracy he had destroyed (read this letter); he published many of his speeches, in which he explicitly confirms his role as protector of the Roman Republic; and he preserved his personal correspondence of years and years with his best friend Atticus. Yet, nobody, not even Cicero, has control over how exactly he is remembered. As a politician at least, he became a tragic figure rather than the hero he purported to be.

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BC), via Wikimedia Commons (source)

In a VIDI project recently started within LUCAS, Christoph Pieper (project leader), Bram van der Velden, and I will for the next five years study the reception and canonization of Cicero. Our main question is: when and how did Cicero receive such an exemplary function as a rhetor and politician? My own research focuses on the historiographical sources from the first three centuries ad, since it is then that the idea ‘Cicero’ rather than the historical figure is consolidated. All later images of Cicero, so it seems, derive from this crucial period of time.

Though we tend to regard reception as a modern phenomenon, it is not just something that happens after antiquity; already in the Roman age intellectuals looked back on their Greek or Republican predecessors. We could define reception as the way somebody or something is looked at, commemorated, or reflected upon in generations in the period after that somebody or something existed. But there are no common theories, no prefabricated toolkits to tackle it. Besides this, my research is not merely culturally or historically orientated. I study the literary tradition, which means I have to deal with problematic concepts as style, intertextuality, imitation, or narratology, and the fact that every text, no matter how historical its nature, offers a thousand interpretations. A scholar who wants to satisfactorily explore a case of classical reception ideally engages with multiple subjects and theories; for me, that is cultural memory (memory studies), literary theory, history, and the political background of Republican and imperial Rome. To give an example of my work I would like to discuss a problem I am currently struggling with. It concerns the moments where reception seem to be hidden in or under the text.

In 63 BC a revolt was nipped in the bud by Cicero, who was then consul. A couple of Roman patricians who had failed to obtain political power sought to take revenge, and mobilised an army of poor and indebted citizens under the guise of a revolution. In four powerful speeches Cicero stimulated the senate to take legal action. After the conspirators were tried, he was officially thanked (the Roman term for this is supplicatio), and in a laudatory speech by Cato the Younger he was proclaimed father of the people (pater patriae).

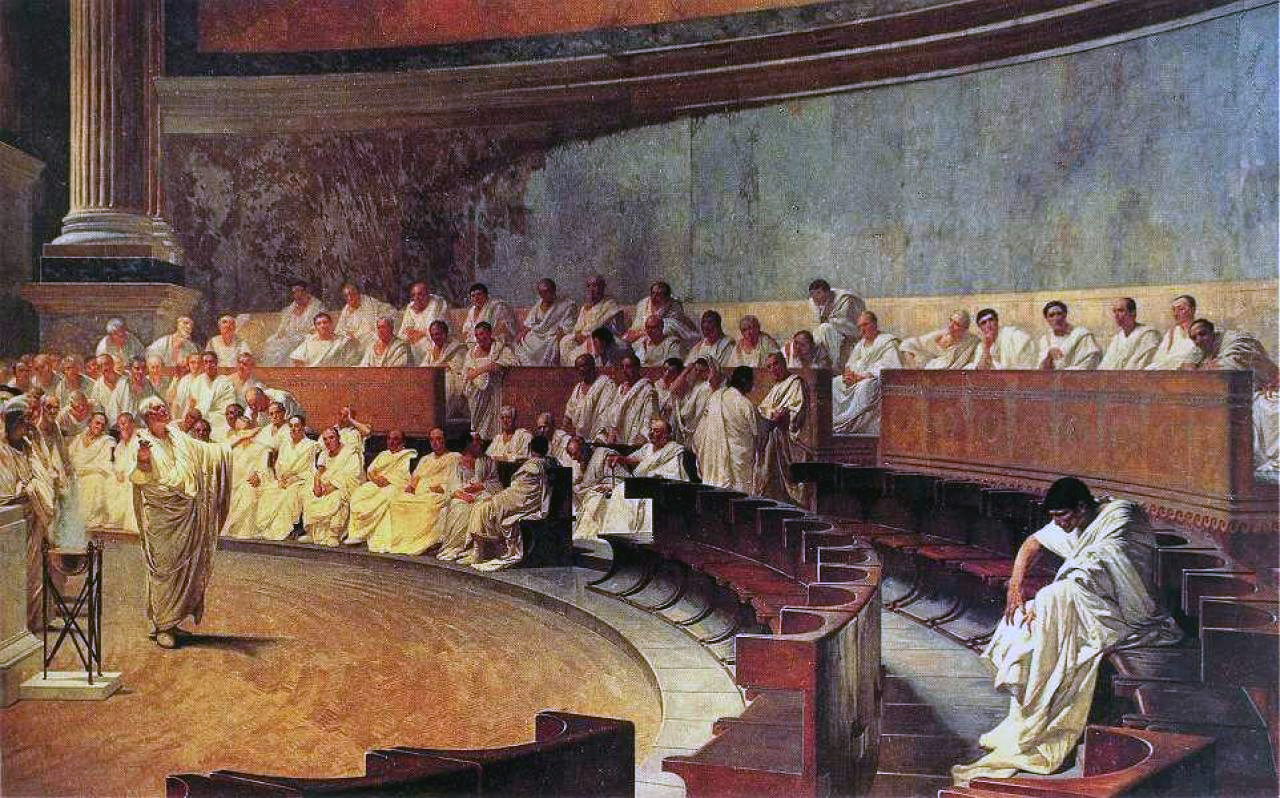

Cesare Maccari, 1889, ‘Cicero denounces Catiline’; fresco now in the Palazzo Madama in Rome. The scene where Cicero holds his first Catilinarian oration, which caused Catiline to flee from Rome, has become one of the most prominent images in the history of the episode, not in the least because of this painting by Maccari. Sallust relates this moment, too, which might have attributed to its symbolic status. (source)

Around 42 BC the ex-senator and historiographer Sallust (86-35 BC) published his version of the conspiracy. His focus is clearly not on Cicero: the leading conspirator Catiline is the protagonist of the story. He is given two full speeches, whereas Cicero’s four speeches are condensed into one single remark about only the first oration: either out of fear for Catiline, or moved by anger the consul held a speech which was impressive (luculentam) and useful (utilem) for the Republic.[2] That Cicero received an official laudatio by one of his political colleagues is left unmentioned, but Sallust does inform us that the Roman people “praised Cicero to heaven”.[3]

Gaius Sallustius Crispus (86-35 BC) (source)

At first sight Sallust’s history does not really appear as a prime example of Cicero reception: for this one would preferably find a text that actually provides you with information instead of withholding it. Moreover, in a process of selection each historian has to choose which pieces of information to present and which to omit. Yet, it is this process that we have to zoom in upon. We are not only interested in the passages where the historical figure in question is treated, we also need to consider the passages where contrary to expectation this figure is missing. Since Cicero’s four speeches are such an important source on the Catilinarian conspiracy, for Sallust as well, it is remarkable when they are practically passed over. Still, passing over is not the right word, for Sallust is offering an alternative: four speeches are made into one; the official laudatio becomes the people’s cheering. Each time traces are left of the moments where the historian chose to forget or omit instead of preserve and commemorate. It is these traces that open the door to the world beyond the text.

All Sallust’s readers remembered Cicero final words from his fourth speech on the Catilinarian conspiracy: “I ask nothing of you, save the commemoration (memoria) of this whole episode and my consulate” (Cat. 4, 23). By writing and later publishing the Catilinarian orations Cicero hoped to safeguard his heroic image for all time. Sallust unequivocally broke this chain of thought.

[1] Aleida Assman, Formen des Vergessens (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2016), 30.

[2] Bellum Catilinae 31.

[3] Idem, 48.

© Leanne Jansen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Leanne Jansen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments