Exploring the Game of Thrones Citadel's library: Knowledge repositories in history and fantasy

Knowledge is power, and libraries are its centres of preservation, both in history and in fiction. How closely does the fantastic Game of Thrones' Citadel Library mirror equivalents from history?

Knowledge is power, as is well known: human civilisations depend on information that can be kept through space and time. Texts, from administrative accounts to chronicles of past times preserved for future generations, have become indispensable, and libraries have grown into centres where these are preserved. In fantasy fiction, some worlds are created in which information and knowledge get passed on through different ways: for example, in Ken Liu's story ‘The Bookmaking Habits of Select Species’ the race of the Quatzoli doesn’t need books like those we’re familiar with, for each of them is a book.

However, most fantasy worlds have libraries that resemble the ones we know, if with a little dose of poetic licence. The Citadel's library, which featured quite prominently in seasons 6 and 7 of A Game of Thrones (GoT), is an example of a fantasy library that clearly mirrors historical counterparts. As George R.R. Martin's saga has been inspired by England and Scotland in the Middle Ages , it’s interesting to explore the parallels between medieval European libraries and the one in Westeros.

Scrolls and codices

A memorable scene in last season’s Game of Thrones — and fans know why — depicts Sam studying and Gilly reading for leisure, at a table covered with old-looking books and scrolls. This is a notable fantastic element in the series, as most European library collections featured only books, called codices. To understand the logic behind that, we must delve into the materials used for text transmission.

Sam Tarly in his study (s.7e.5). Image HBO, via The Daily Dot

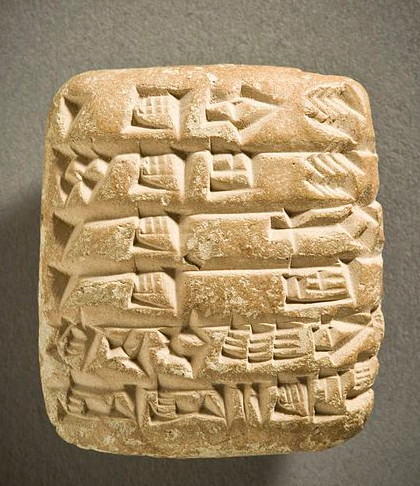

Perhaps the oldest structural writing support was the clay tablet, used from about 4000-1000 BC. Scribbles on these developed into cuneiform, a complex sign system that was mastered only by highly trained scribes. The first libraries, which could contain thousands of tablets, were located in Sumer, Babylonia, and Assyria. But clay tablets were heavy, and cumbersome as they could only be inscribed when the clay was still wet. Therefore, around the Nile a cheaper and more flexible writing support was developed: papyrus (from 2900 BC). Papyrus sheets were made of thin strips of reed, and several sheets could be horizontally attached to each other. Since the sheets couldn’t be folded without breaking, they were stored as rolls, called scrolls. However, this material had some disadvantages, too: for one, it didn’t fare so well in humid climates — quite a fundamental hindrance in real-life Western Europe, as well as in the Westerosi North, the Riverlands and the Iron Islands, to name a few locations!

Cuneiform Tablet, Mesopotamia, circa 2052 B.C. LACMA M.41.5.1b. Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Oxyrhynchus papyrus, dated 75–125 A.D. It describes one of the oldest diagrams of Euclid's Elements. Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Therefore,parchment and later paper became much more popular writing supports, in Europe and Westeros.* With their use, the arrangement of texts changed too, as parchment and paper could be folded into sheets and stitched together, to make a codex (plural: codices). The advantages of the codex are not to be underestimated: books are easier to transport, store, and consult. Although the Vatican continued to use scrolls until the 12th century, most texts were produced in parchment codices by the 4th century. Libraries, too, prefered the codex for knowledge preservation, and from the 11th century most European libraries contained solely codices. So, while the scrolls give Sam’s study and the Citadel's library in GoT the flavour of ancient knowledge, they actually didn’t last very long.Navigating the library

It remains unclear in GoT precisely how many books are held in the Citadel’s library. Jon Snow tells Sam that there are ‘so many books at the Citadel that no man can hope to read them all’ (A Dance with Dragons, ch. 7), but a quick calculation shows that doesn’t say much: assuming a dedicated scholar could read three books a week, for seventy years of his life if he grows into ripe old age, that still amounts to no more than 10,000 volumes. In the series, however, the Citadel’s collections seem much larger than that — impressively vast, to be honest.

The Citadel library through Sam’s eyes. Still from HBO’s Game of Thrones s.6 ep.10.

This made us book researchers wonder: how do the Westerosi maesters navigate such a dizzying repository? We know that medieval and early-modern European libraries had their collections organised by subject matter: books on mathematics, on philosophy, or on history grouped together in open stacks for the user to browse. Such systems can work well if highly skilled specialists want to use collections of limited extent, say, a couple of thousands of books — for example, scholars exploring early-modern university libraries, such as Leiden University Library around 1610, when it contained such a number of volumes.

Leiden University Library; engraving by Swanenburgh after a drawing by Woudanus, 1610. Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Larger repositories require navigation aids to access the collection, and most libraries have employed the combination of catalogues, for the user to browse, and trained librarians, to collect any books that users request. Oxford’s Bodleian Library, for instance, contained approximately 16,000 books when it issued its first printed catalogue in 1620, which users had to buy at their visit. Trinity College Dublin’s original eighteenth-century library, now called The Long Room, had its 100,000 books in numbered stacks and coded shelves to allow access. Without such retrieval aids, users would never be able to use the collections effectively. Jorge Luis Borges pursues this notion of accessibility in his fable ‘The Library of Babel’, in which he created a vertiginous labyrinth of similar rooms filled with uniformly sized books, where library patrons roam through eternity looking for the one book that would explain the system and therefore all other books.

The Long Room, Trinity College Dublin, Ireland. Photo by David Iliff, CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Citadel doesn’t seem to have catalogues, coding systems, or helpful librarians to assist users. Note, moreover, that the books in the Citadel's library don’t have titles mentioned on their spines. Although we, modern readers, expect all books to be labelled in this fashion, it is actually a fairly recent practice. This is related to book shelving customs: the first libraries stored their books flat, then vertically with the spine to the back of a shelf, and only finally with the spine facing the outside. Although some front covers were labeled with title information and, from the 15th century onwards, some books had beautiful and effective decorations on their fore-edges, the title-information on the spine seems to be an early-modern invention.

Yet despite the absence of visible retrieval aids, coding systems, or catalogues, and while he is by no means an expert librarian, GoT’s Sam Tarly is able to reshelve books in the Citadel, as part of his chores in his first weeks as a novice (s.7 ep.1). In our opinion, this is a truly remarkable feat, rivalling Daenerys’ dragon riding and Arya’s sword skills — or is it another piece of GoT magic?

Chains and the restricted section

The chains in the library of the Citadel. Still from HBO’s Game of Thrones, s.6 ep. 10.

Since antiquity, the majority of libraries have been owned by worldly and religious leaders and their supporting institutions, and they were usually not open for public use. With the rise of the universities and monasteries as centres of learning, the audience for their libraries started to increase, and they sought to secure their precious assets. Books were extremely valuable, because of their materials and hours of manual labour involved in their production; moreover, of some titles only a limited number of copies existed (and almost never more than one per library). In some reference libraries where patrons could access the shelves directly, books were chained from one of the front corners, to prevent theft. Such was the case of the library at Leiden University around 1610 (as can be seen above), and also, for instance, at the 16th-century public city library, the Librije, in Zutphen. As many viewers have pointed out, books in the Citadel's library are chained as well; a clear nod to their inestimable worth for the maesters of Westeros.

The Librije, chained library in Zutphen, the Netherlands. Photo: Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Many modern libraries keep their most precious old or rare books in a Special Collections department. Although these are accessible for designated users under strict supervision by librarians, the books are safeguarded from the general public. In history, some libraries have done the opposite: protecting patrons from certain books. In these libraries, specific materials deemed unsuitable for most readers were located in ‘restricted sections’, to which only accredited patrons would get access. One example of this practice was the Private Case-collection of the British Library, which contained ‘dangerous texts’, such as obscene fiction, sexually explicit images, and treatises on sexuality.

While it is not specified in the GoT-series which part of the Citadel's collection is restricted precisely, one wing of the library is clearly marked as such, with a locked gate behind which scrolls are gathering dust (s.7 ep.5). Like most viewers, Sam is immediately triggered: he is on a quest to find out how to kill the White Walkers, and knows most maesters regard this topic as dangerous nonsense. As Sam is only a novice, it’s no surprise that Archmaester Embrose denies him access, in a scene unintendedly parallelling that other major fantasy fiction in which students are excluded from a magical part of the library. Fortunately for us — and for Jon Snow — resourceful Sam steals a key (and we’ll not spoil what happens after).

Concept design for the Citadel Library in the HBO series A Game of Thrones, by Kieran Belshaw via ArtStation. Reproduced with permission of the author.

Despite some differences, A Game of Thrones definitely mirrors medieval and early-modern European libraries, in its contents, organisation, and use policies. In the end, however, the aspect in which the Citadel resembles real-life historical libraries most vividly, is in the awe and amazement they inspire in their users. Hopefully, Sam’s ecstatic look when he first enters the Citadel's library inspires many viewers and readers to visit equally beautiful places of knowledge and learning, such as the ones portrayed in this post — because when you come to think of it, in our real world that’s where the magic happens…

Let us know in the comments: what is the most beautiful library you have ever visited?

Göttweig Abbey Library, Austria. Photo by Jorge Royan, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

* A note on parchment versus paper: in the original A Song of Ice and Fire fantasy novels by George R.R. Martin, parchment seems to be the dominant writing material in use for letters, declarations, maps, books, etc. See ‘A Wiki of ice and fire’, to find an abundance of citations from all books. For the HBO TV series, the prop-makers have used paper instead of parchment (see for instance the close-ups on the props here); we assume this is for cost-efficiency and empathy for animals, as parchment is made of animal skins.

HBO owns all rights to images of the TV series A Game of Thrones. We have included a limited number of images from the TV series in this blog post, only where and when we thought them essential for the reader's understanding, and in line, we believe, with the educational and scholarly (non-commercial) purpose of the Leiden Arts in Society Blog. Kieran Belshaw's concept design, via ArtStation is reproduced with permission of the author.

© Fleur Praal, Andrea Reyes Elizondo, and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2017. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Fleur Praal, Andrea Reyes Elizondo, and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments