Helena Spanjaard: “Hey, this is funny, they make modern art here”

In this post Dutch art historian Helena Spanjaard recounts her journey to become the first Dutch art historian on Indonesian modern art in the Netherlands, and the unfolding of the discipline of modern Indonesian art history in her country.

For the first post of this blog entry, Helena explained the general proposition of her most recent publication: the relation between Indonesian art and Dutch colonialism. Now, we remember the emergence of the field of modern and contemporary art history from Indonesia in Leiden University through her personal experience.

Helena Spanjaard receiving her Doctoral degree in the Large Auditorium of Leiden University, 3rd June 1998

How did you become a researcher in Indonesian art?

From the start, I was blank, which is good. I am not sentimental about colonial history, because I do not come from a family that lived in Indonesia.

Before I was trained as an art historian, I studied Graphics in an art academy, the Rietveld Academy. This is why I analysed the history of Indonesian art academies. It’s just an aspect, but an essential one to understand the development of Indonesian art.

My biggest problem in the past thirty-five years is that I had no colleague in Indonesia. Nowadays, there are some young scholars who have studied in Australia, in the USA. That’s good, the development is visible, but [to this day] there is no faculty of art history at any university in Indonesia.

And here, in the Netherlands?

Well, here I found Prof. Kitty Zijlmans as one of the few art historians who was willing to create a new field of modern Asian art. But when I started my research in 1980, it was extremely difficult to find a supervisor.

Reception at Leiden University on Helena’s graduation day. On the image Prof. Kitty Zijlmans speaking to a colleague holding Helena’s dissertation. In the background, the referent Prof. Dr. Haryati Soabadio, from Universitas Indonesia

H.L.C. Jaffé, my professor in Amsterdam, was a very brilliant man. His reputation is international because of his own dissertation about DeStijl. You remember the painting you liked in my living room? It was made by Bandung artist Anton Kustia Widjaja (1935-85). There is an interesting connection: in 1981, Jaffé opened this exhibition in Amsterdam. Impressed by the artworks, he suggested me to pursue a PhD in modern Indonesian art, but he died before I got the diploma.

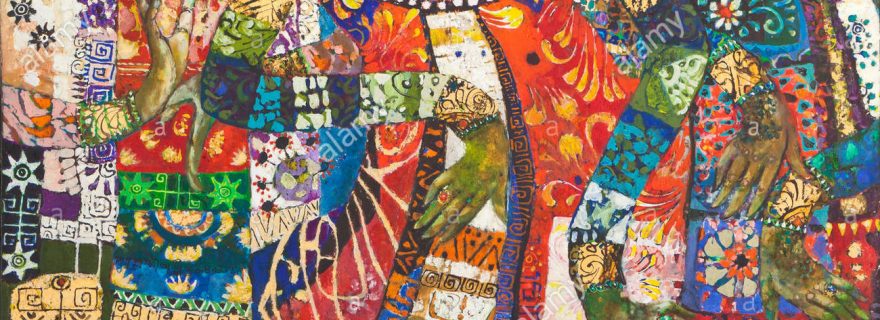

The painting Three masked dancers (1981), by the Bandung artist Anton Kustia Widjaja

Besides Western art history, I studied art and archaeology of South and Southeast Asia. This course does not exist anymore. My main interest was Hinduism and Buddhism, not Indonesia.

Where did you study this course?

In Amsterdam. It was very exceptional that you did not need to know an oriental language. In Leiden, you needed a degree in an oriental language to be able to study this subject. In fact, the professor who gave the course came from Leiden.

This is interesting, that you would need to be a linguist before you do art history.

Yes, and it has consequences. Leiden University – I can analyse it now – was the central point of studies about Indonesia in the colonial time. So, these studies were framed in a certain colonial way. Language is of course essential, otherwise you cannot understand the people.

In the past, Leiden offered courses for government officers that went to Indonesia: they learned how to rule a country, government systems, Javanese adats (traditions), local power structures, and languages. Besides that, there were the anthropologists, who studied “interesting” Javanese or Balinese people, and their traditional art. This is very complicated for art historians, you know. Art historians do not have a clear placing within disciplines: you have the anthropologists who study the people and local costumes, including what they make [traditional art]. And then, you have the archaeologists (and I studied that part) who studied the medieval art of Indonesia – the Borobudur and the Prambanan. The Jakarta National Museum still has this collection of archaeology and artefacts, which was made by the Dutch.

The interior of the Jakarta National Museum containing several archaeological remains

And the Indonesians never question the research methods of the Dutch?

Here we get to politics. This whole “glorious past” was used by Suharto. That is the word I used in my dissertation – Indonesianisation. It’s hypocrite because they glorify the glorious time of Prambanan and Borobudur, yet they don’t make an effort to make them clear world-class tourist destinations. Borobudur is known as one of the main five Buddhist sites, but I have been there some years ago, and it looks sad.

How did you get to Indonesia?

In 1978 I made a second journey to the east – Sri Lanka, India, and later Indonesia. I just wanted to see Borobudur. But I had one name card with me, and this card changed the course of my life. Faridah Srihadi, a woman artist from Bandung, whom I knew from the Rietveld Academy, gave me her husband’s card, without even mentioning he was one of the most famous Indonesian artists.

Srihadi Soedarsono and his wife Faridah Srihadi in 2016

Instead of Borobudur, her husband [Srihadi Soedarsono] took me to the art academy in Bandung! And I thought: “hey, this is funny, they make modern art here!”

Did you witness the GRSB (New Art Movement) protests, that occurred between 1975 and 1979?

No, because I was a tourist, and a guest of the professors. At that time, the hierarchy between professor and students was very strong. I was totally guarded by the teachers: they spoke Dutch, and they liked to speak Dutch. They belonged to the elite; the art academy of Bandung is very elitist.

The Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB). The Dutch architect Henri Maclaine-Pont designed the central building, incorporating local styles

And then you went to Borobudur.

Yes, after few days, I went to Borobudur, and then Bali, where I met the painter Anton Kustia Widjaja. He is interesting; he came from Bandung, lived in Bali, and did what would be classified “Balinese art”, but in fact belonged to the category of modern Indonesian artists from other islands that move to Bali for inspiration.

The painting Borobudur – Prosperity of Soul, by Indonesian artist Srihadi Soedarsono

Back in the Netherlands, I prepared my research and later lived in Indonesia from 1984-6. When I returned, the successor of Prof. Jaffé was not very enthusiastic about my subject. So I finally moved to Leiden University, supervised by Prof. Reimar Schefold (anthropology) and Prof. Kitty Zijlmans (art history).

What does the field look like today?

I always have a feeling that artists are most interested in my work, more than the academic world. Nowadays, going to Indonesia is like going home. Here, my work is accepted because we [Netherlands and Indonesia] have a special relation. But internationally, there are very few specialists in Indonesian art history. The majority still comes from the field of linguistics or has an anthropological approach. An exception is my good friend, Prof. Astri Wright (University of Victoria), who combined several research methods (art history and anthropology) in her dissertation for Cornell University.

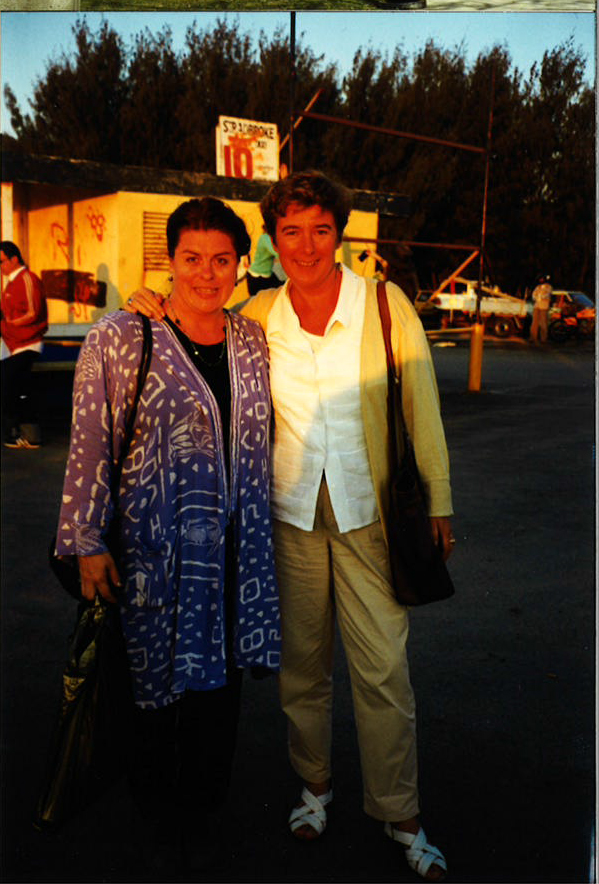

Dr. Helena Spanjaard and Prof. Dr. Astri Wright, in the exhibition “Beyond the Future,” the Third Asia Pacific Triennial, in Brisbane, in 1999

A similar attitude can be found in the dissertation of Apinan Poshyananda, a Thai artist, who came to the West to be trained in art history at Cornell.

What will your next book be on?

It will be on Ries Mulder, about the establishment of the Bandung academy in 1947 until he left Indonesia in 1958. This is a crucial year; all Dutch had to decide if they remained and become Indonesians or leave. Mulder is highly important; he educated some of the best Indonesian painters.

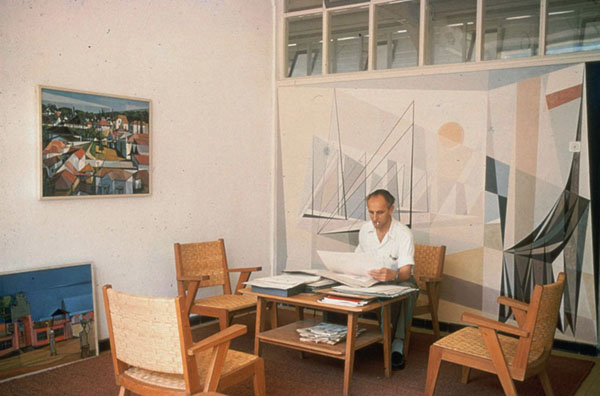

Dutch artist Ries Mulder inside his atelier in Bandung, in 1956.

© Leonor Veiga and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Leonor Veiga and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

.jpg)

0 Comments