It’s a Small World: The Dollhouse in the Seventeenth-Century Netherlands

A small corpus of extant seventeenth-century Dutch dollhouses shares traits with other contemporary collecting practices, but demonstrates different potentials for microcosmic thinking.

The Dutch Golden Age dollhouse is having a bit of a moment. Jessie Burton’s best-selling novel The Miniaturist centers on the wife of a wealthy Amsterdam merchant who furnishes her lavish dollhouse with gifts from a mysterious miniaturist; a BBC miniseries based on the book—filmed in our own Leiden on the Rapenburg—was aired in 2017 and 2018; and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts recently acquired a collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Dutch miniatures, housed within a recreation of a period dollhouse. Interest in these objects has thus soared, but to understand the significance of the Dutch dollhouse one needs to first examine the broader collecting practices in which they were collected and assembled.

The dollhouse of Petronella Oortman, c.1686-1710. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. BK-NM-1010

The dollhouse of Petronella Dunois, c.1676. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. BK-14656

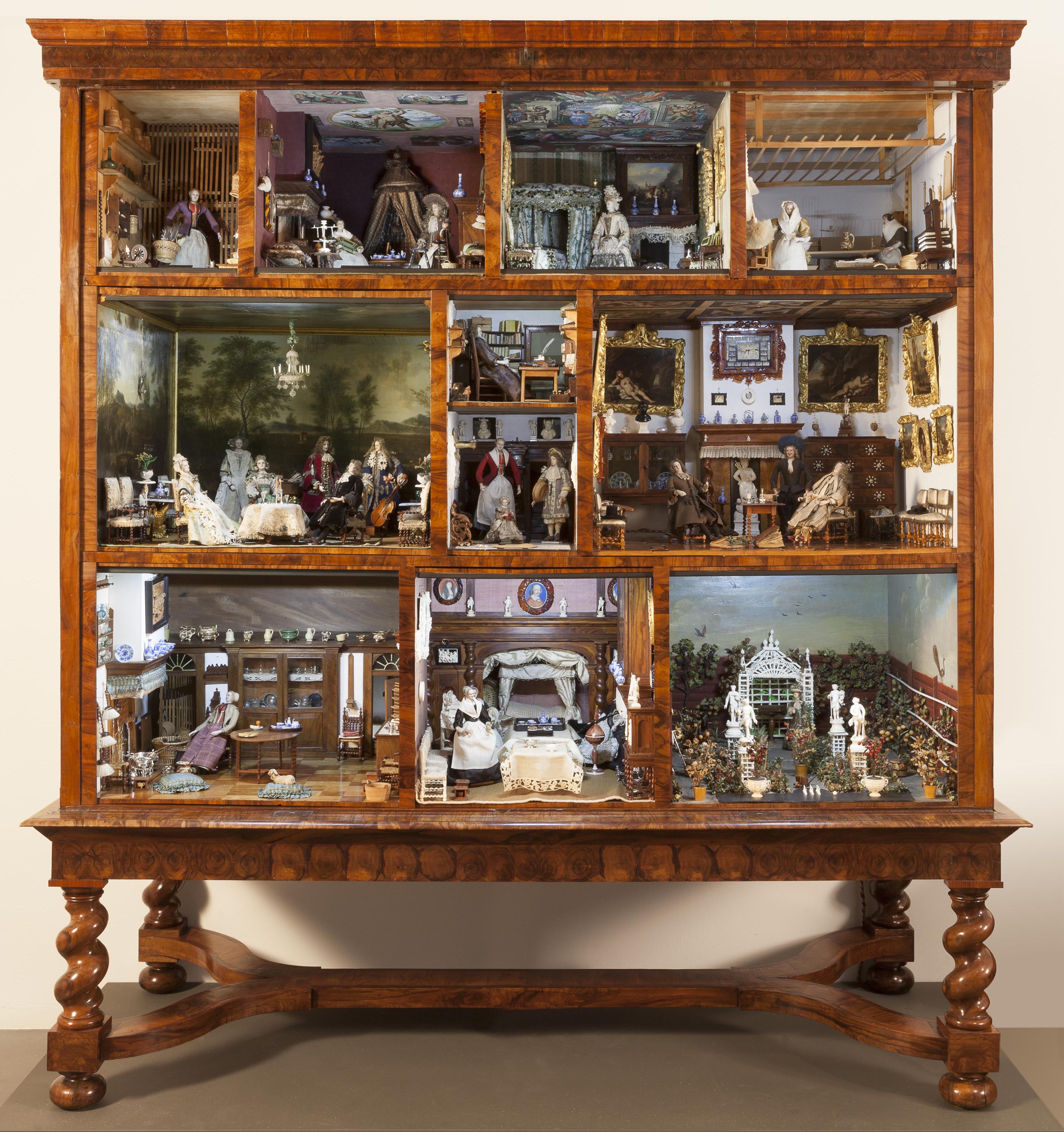

The dollhouse of Petronella Oortmans de la Court, c.1670-90. Centraalmuseum, Utrecht. Inv. Nr. 5000 [image copyright CMU]

There are three extant seventeenth-century dollhouse cabinets, which by some strange quirk of history were all assembled by women named Petronella (also the name of Burton’s protagonist). The most famous and lavish example is that of Petronella Oortman, now in the Rijksmuseum, displayed alongside that of Petronella Dunois. The third—in the Centraalmuseum—is that of Petronella Oortmans de la Court (no relation to the aforementioned Oortman). Two eighteenth-century examples were created by Sara Rothé from dismantled parts of dollhouses assembled in the previous century by Cornelia van der Gon (these at the Frans Hals museum and Gemeentemuseum). These five examples give a good sense of what set the dollhouses of the Dutch Golden Age apart from those made elsewhere before and after. Unlike most dollhouses, these took the form of cabinets with closable doors, which from the outside had no semblance of a miniature house. They were made of the most precious materials, incorporating ebony, brazilwood, ivory, silver, and porcelain; and the craftsmanship of both the cabinets and their contents was of the highest quality. They were moreover not made for children or for play, but were instead the result of a serious collecting practice and the purview of a small group of very wealthy women. One eighteenth-century viewer estimated that Oortman’s cabinet must have cost between twenty and thirty thousand guilders—rivalling the cost of an actual canal home, fully-furnished. Though this estimate likely far exceeded the true cost, it speaks to the overwhelming extravagance of the dollhouse and the impression it must have had on viewers.

On account of their form, cost, and materials, Dutch dollhouses have often been related to the curio-cabinets and wunderkammern of the early modern period. In these cabinets and rooms, collectors—generally men—collected exotica, natural specimens, curiosities, and examples of fine craftsmanship. They were seen as representations of the world in microcosm, or “a world of wonders in one closet shut,” containing specimens from all over the world, of all manner of animal, mineral, plant, and crafted object.[1] The microcosmic thinking behind the curio-cabinet reflected similar ideas manifested in cartographic and scientific endeavors, which aimed to collapse the complexities of the world into a map or magnifying lens. Like their curio-cabinet counterparts, Dutch dollhouses were contained within cabinets, fashioned from rare and costly materials, and filled with examples of exquisite craftsmanship. They similarly organized the world into discrete compartments, each with its own domain. While an early modern Wunderkammer might contain objects grouped by geographic origin or material properties, the dollhouse organized the rooms through their ostensible functions in the domestic sphere: the kitchen, the sitting room, the study, the nursery—each had its place and was furnished accordingly.

But the microcosmic logic behind the wunderkammer differed in a significant way from that of the dollhouse. The scope of the former was always going to be limited, as any specimen could only stand in for a much larger corpus. A shell might stand in as a representative of all shells of that variety, or of all shells in general. Its relationship to the greater world was synecdochal, but in a dollhouse objects weren’t functioning as representatives of greater genera. In this way, their microcosm was more of a closed system.

A salon room from the dollhouse of Petronella Oortmans de la Court, c.1670-90. Centraalmuseum, Utrecht. Inv. Nr. 5000 [image copyright CMU]

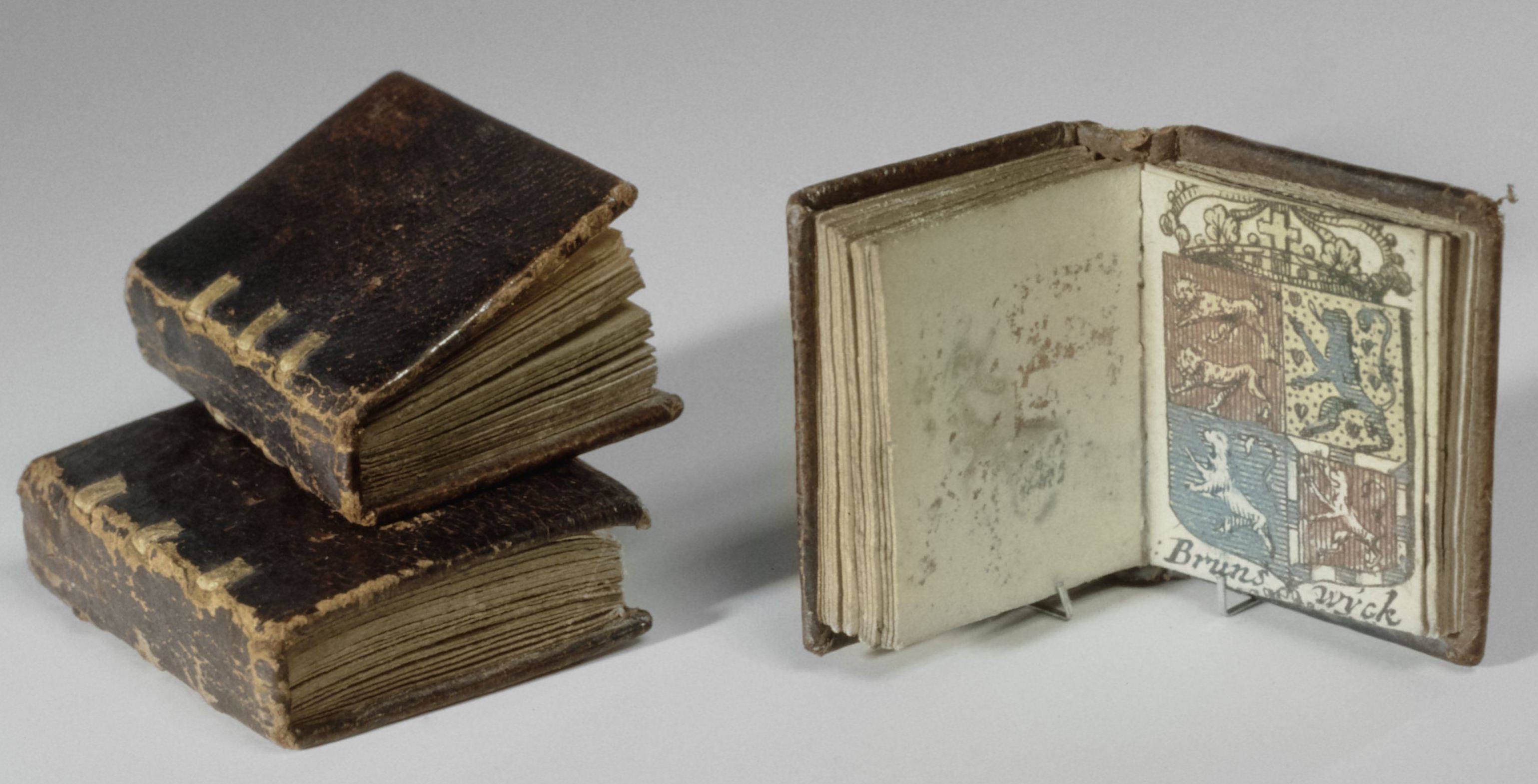

Of course, a dollhouse object might resemble a full-size equivalent, but contrary to what has sometimes been claimed, no dollhouse owner commissioned exact replicas of her home or its contents in miniature. These were original objects, if exiguous. Miniatures were often made of the same materials as full-size objects, and in some examples they were made by the selfsame craftspeople. The miniature paintings by David van der Plas that hung on the walls of Cornelia’s dollhouses were not simulacra of Van der Plas paintings, they were his paintings. Dollhouses held works by the same hands that furnished regular-sized art collections. The wicker baskets were woven strand by strand in the same meticulous manner as full-size examples. The silk was real silk, the linen real linen. Books were fashioned from details of prints cut down and bound together, and some of the porcelain was actually commissioned and shipped all the way from China. Oortman’s dollhouse features a miniature curio-cabinet filled with actual tiny shells—it is not a representation of a shell collection, but rather is one. In this way they differ significantly from eighteenth-century miniatures which are often all made of silver—be they baskets, chairs, plates, etc. The objects within Cornelia and the Petronellas’ dollhouses are imbued with all the materiality and craftsmanship of their full-size counterparts, merely condensed and stripped of their utilitarian functions.

Books from the dollhouse of Petronella Oortman, c.1690-1710. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. BK-NM-1010-148-A

A miniature cabinet of shells from the dollhouse of Petronella Oortman, c.1690-1710. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. BK-NM-1010-2

The fascination with dollhouses came then, as it does now, from this reduction of scale without compromising the potency of a given object. In his Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard claimed that:

"The cleverer I am at miniaturizing the world, the better I possess it. But in doing this, it must be understood that values become condensed and enriched in miniature. . . . One must go beyond logic in order to experience what is large in what is small." [2]

Cornelia and the Petronellas were indeed very clever at miniaturizing their worlds, and they did so at the expense of much time, effort, and resources—both their own and of those whom they commissioned. All of that labor and material was then imbued into the objects in the microcosm of the seventeenth-century Dutch dollhouse. As the adage goes, multum in parvo; there is much to be found in the small.

[1] This description taken from a seventeenth-century English collector’s epitaph. Paula Findlen, Possessing Nature (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 17.

[2] Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas (Boston: Beacon Press, 1994), 150.

Further Reading

On Dutch Seventeenth-Century Dollhouses:

Broomhall, Susan, and Jennifer Spinks. Early Modern Women in the Low Countries: Feminizing Sources and Interpretations of the Past (chapter 4). Ashgate Publishing Group, 2011.

Moseley-Christian, Michelle. “Seventeenth-Century Pronk Poppenhuisen: Domestic Space and the Ritual Function of Dutch Dollhouses for Women.” Home Cultures 7, no. 3 (2010): 341-363.

Pijzel-Dommisse, Jet. Het Hollandse Pronkpoppenhuis: Interieur en Huishouden in de 17de en 18de eeuw. Zwolle: Waanders, 2000.

On early modern collecting practices:

Findlen, Paula. Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. Berkeley [etc.]: University of California Press, 1994.

On miniatures and the small:

Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. Translated by Maria Jolas. Boston: Beacon Press, 1994.

Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press, 1993.

© Jun Nakamura and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jun Nakamura and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments