Jeff Koons' Broken Artwork and Tactile Desire

After a visitor broke Jeff Koons' Gazing Ball (Perugino Madonna and Child with Four Saints), which was exhibited in the Nieuwe Kerk, the curator expressed his surprise about visitors touching art. In this post I argue that it is actually common practice.

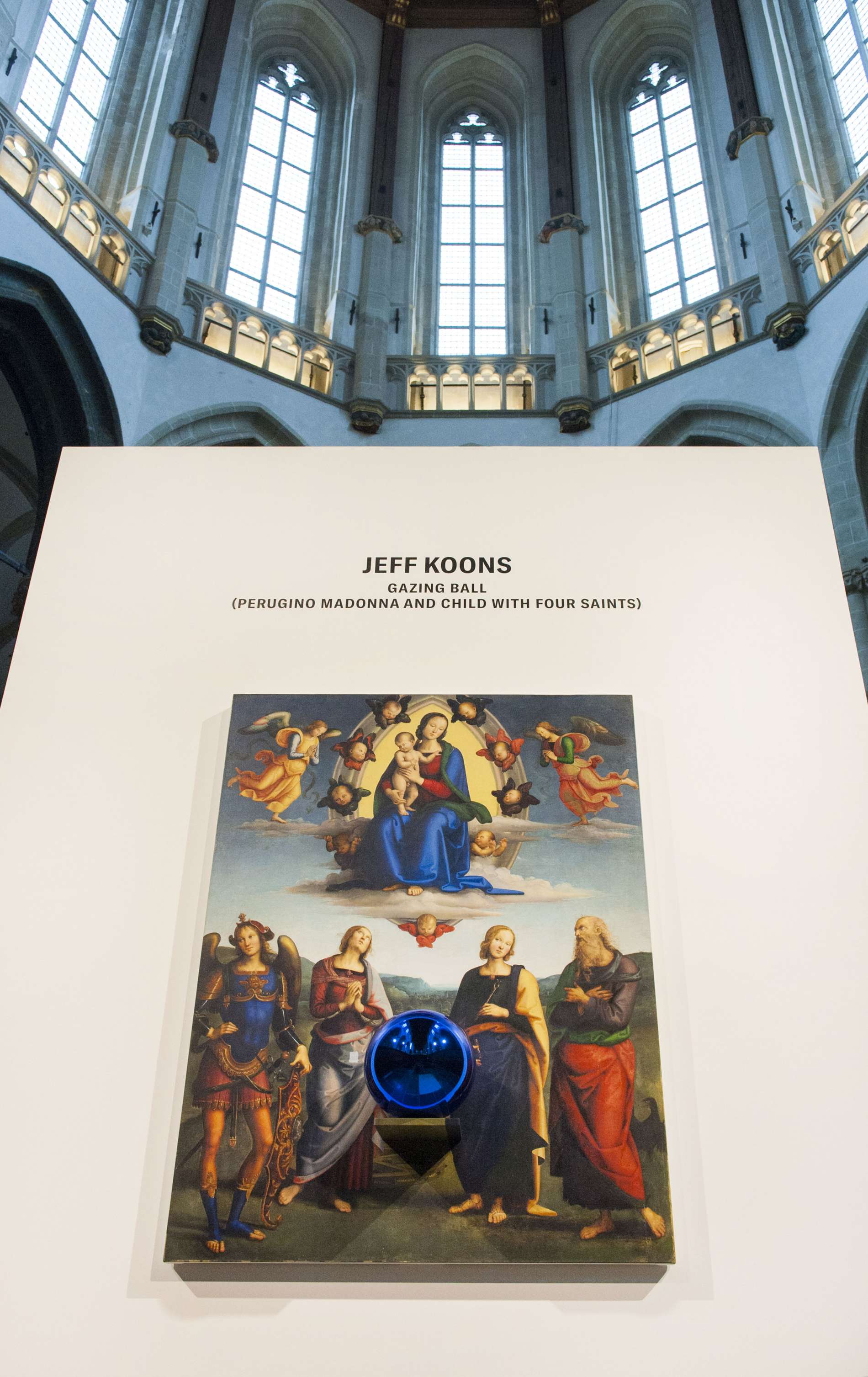

Each year, the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam exhibits an art work from a well-known artist as part of their series Masterpieces. In previous years work by Rembrandt, Andy Warhol and El Greco could be admired in the impressing church setting. This year it was Jeff Koons’ turn. Koons is known for his ‘readymades’, his use of popular culture and banality, and his references to the art historical canon. In his series ‘Gazing Ball’, Koons uses replicas of iconic artworks, produced by young artists, and adds a royal blue glass ball, in which viewers can see their own reflection. The artwork exhibited in the Nieuwe Kerk included a replica of Perugino’s Madonna and Child with Four Saints, a Renaissance painting dating from c. 1500.

Pietro Perugino, Madonna and Child with Four Saints, c. 1500, Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna (wikimedia commons)

On Sunday April 8th, the last day of the exhibition, something unexpected happened: a visitor touched the ball, and with a loud bang it broke into pieces. Apparently, no harm was intended. In previous years the masterpieces were showcased behind glass, but this was not done this year because it would have affected the reflections in the glass ball. Instead, the artwork was permanently guarded, but this did not always prevent visitors from getting close to the artwork.

Jeff Koons' Gazing Ball (Madonna and Child with Four Saints) exhibited in the Nieuwe Kerk, Amsterdam. Photo Janiek Dam

While it is not entirely clear whether the visitor touched the ball on purpose or by accident, curator Gijs van Tuijl comments in the Volkskrant that he does not understand why anyone would touch it: “Who touches a mirror? I find that very strange. It cannot happen, it should not happen and it may not happen.” While Van Tuijl may be surprised at someone touching an artwork, I have to admit I was surprised when reading about his surprise. Has he never felt the urge to touch something in a museum? I myself have certainly felt this sensation at times. At other times I have tried to convince my friends that they were not allowed to touch a certain artwork in a museum, while they insisted that the artwork invited to be interacted with – and I could not completely disagree. This tumblr with photos of people touching museum exhibits is an indication that it is a very common practice. In this post, I would like to argue that it would actually make sense for someone to touch Koons' work.

The urge to touch

Prof. Fiona Candlin has written about the unauthorised touching of objects in museums that is not aimed at damage or destruction. She observed and interviewed visitors and attendants in the British Museum. She found out that there were several recurring reasons for visitors to touch the exhibits: to check whether the object is real or a replica (which is a difficult question with regard to Koons' work), to get a sense of the material qualities, or to feel a connection with the past. Some objects were touched significantly more frequently than others, with visitors arguing they were so inviting that it was almost impossible not to touch.

Civil Disobedience in the British Museum. Photo by Erik Schepers (creative commons)

What makes the urge to touch so irresistible? First of all, neuroscience has shown that the sense of touch is very sensitive and actually the first to develop in humans. This makes tactile desire hard to restrain. Moreover, touching something can give information that the other senses can’t provide, mainly with regard to the material. Candlin found that certain materials such as marble were harder to resist than others. I can imagine that a reflecting glass ball would also fall into this category.

Candlin wants to rehabilitate the illegal touchers of objects, and argues that touching gives them agency. This reminded of something Koons said about his Gazing Balls series: “This experience is about you, your desires, your interests, your participation, your relationship with this image.” Thus, the artwork was supposed to have an alluring effect on the beholder.

The modern art museum and the gaze

Look, don’t touch: that is how we are supposed to behave ourselves in an art gallery. While it is easy to take this adagio for granted, it is important to bear in mind that most of the art you see in museum originally functioned in a very different way. Perugio’s painting of Madonna and Child with Four Saints, for example, was made as an altar piece for the Scarani Chapel of the church of San Giovanni in Monte. While it may not necessarily have been touched by the church attendants, it functioned in a multisensory environment with music, preaching, frankincense and the tactile and gustatory sensations of the Eucharist. The setting of the Nieuwe Kerk and the singling out of one masterpiece creates a similar aura of veneration, and perhaps only satisfying the gaze is not enough in such a sacred context.

San Giovanni in monte, Bologna (Wikimedia commons)

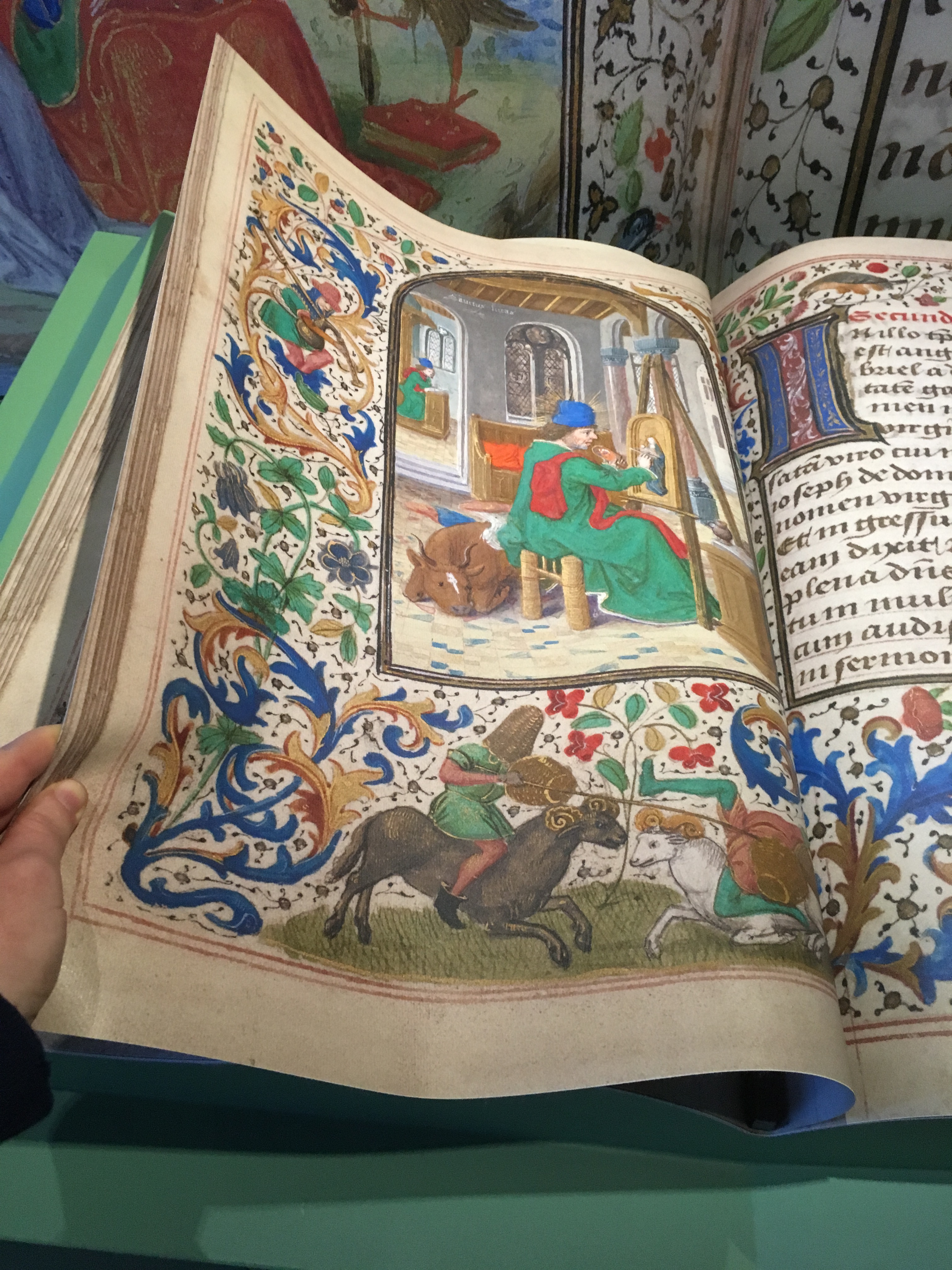

Moreover, in the medieval and early modern period it was quite common to touch objects that are now kept in museums, such as the baby Jesus dolls and manuscript illuminations that I have blogged about previously. The problem of transposing holy objects to a museum setting as been shown by Saloni Mathur and Kavita Singh in a book on the museum in South Asia, where visitors ignore instructions not to touch objects and not to pray inside the museum.

Even in museums touching the exhibits has not always been off-limits to the visitors. In the cabinet of curiosities, which can be seen as the precursor to the museum, touching was an important part of exploring the collection. In the museums of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, which didn’t attract or allow as many visitors as the modern museum, touching was also common practice. Luckily, some museums nowadays incorporate multisensorial aspects in their exhibitions. In the current exhibition Magical Miniatures in museum Catharijneconvent for example, the smell of medieval manuscripts has been recreated, and visitors can turn the leaves of a giant reproduction of a book of hours. At the Univeristy of Leicester, Museum Studies PhD student Armand De Filippo has established an experimental exhibition where visitors can touch, smell and taste the blood, ink, pigments, animal hide and frankincense of manuscripts.

Touching a giant fake manuscript in Museum Catharijnceonvent. Photo by the author.

To conclude, the practice of touching art is quite common and no reason for surprise. Of course, it is unfortunate that in this case the artwork broke (although NRC commentator Joyce Roodnat recently suggested it actually adds to the artwork by creating a narrative around it). But can we really blame curious visitors for wanting to experience the materiality of art?

Further Reading

Cara Giaimo, ‘Why Can’t People Stop Touching Museum Exhibits?’, Atlas Obscura

‘Please Do (Not) Touch the Art’, Psychology and Neuroscience

DISCLAIMER: This blog post is not meant to encourage the touching of museum exhibits. The author and the Arts in Society Blog are not responsible for any damage.

© Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments