Looking at the Past: The Task of the Theatre Historian

What would it be like to travel to the past and watch a production of Shakespeare’s Hamlet at the Royal Theatre Drury Lane in 1812? Fernanda Korovsky Moura reflects on how the theatre can help us recreate and understand the past – without a time machine!

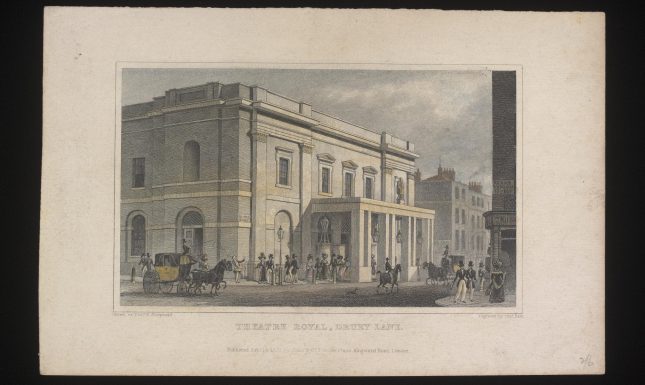

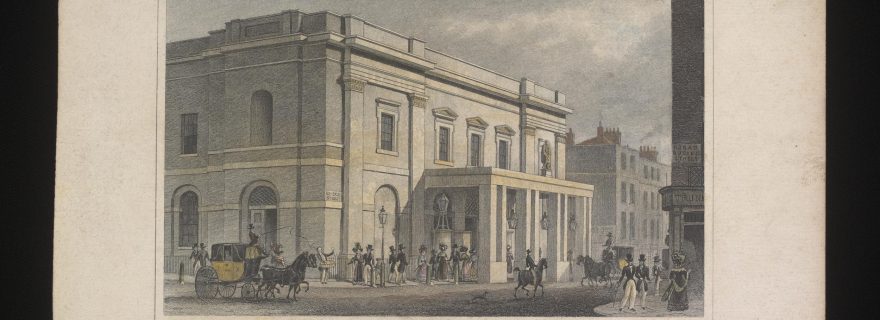

What would it be like to go through the arched doors, walk past Shakespeare’s statue in the main hall, sit on one of the stuffed chairs in a private box and watch the opening season of Hamlet at the Royal Theatre Drury Lane in October 1812? That is a question I often ask myself. It has perhaps never crossed your mind (until now), but questions like this guide the journey of a theatre historian.

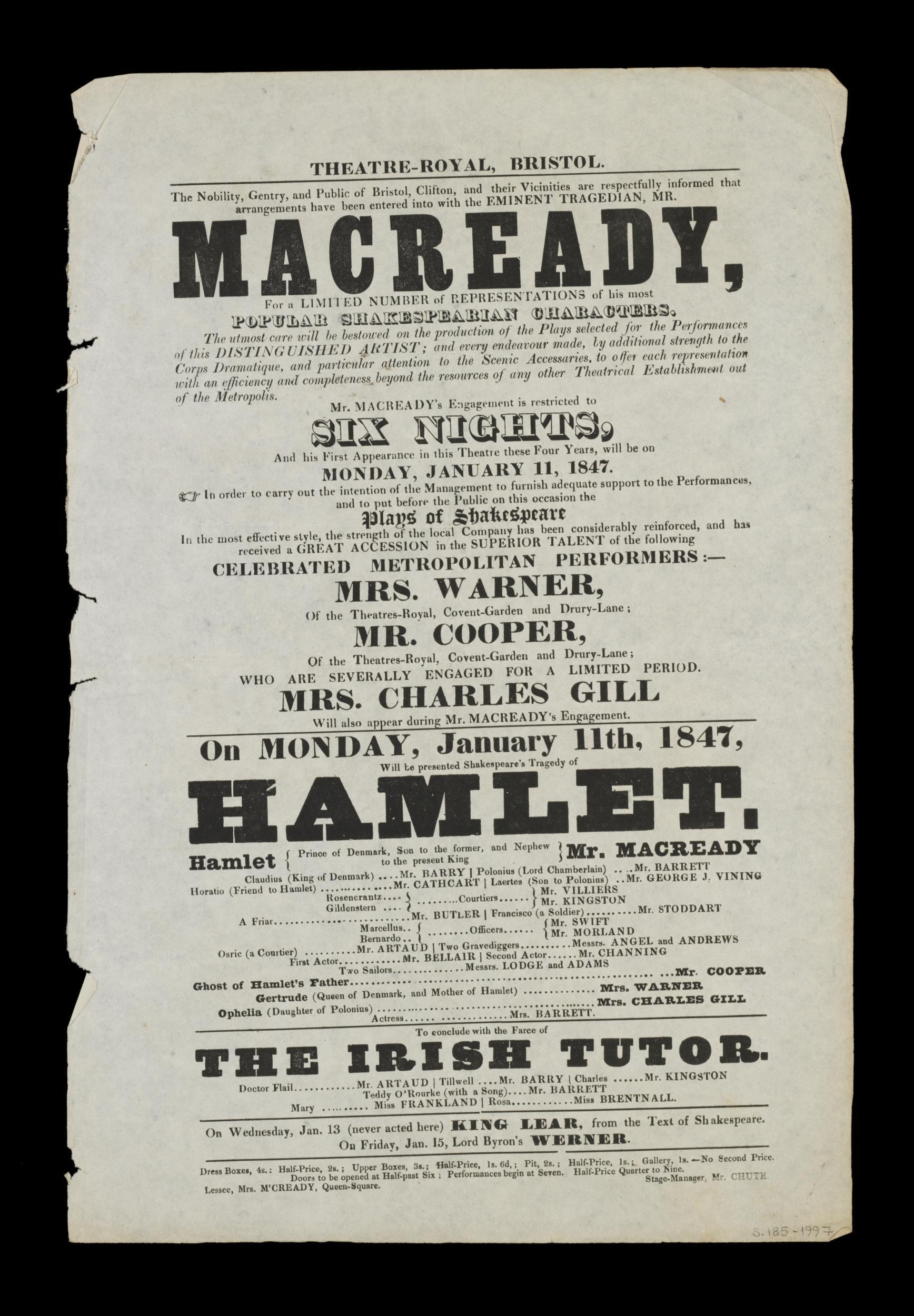

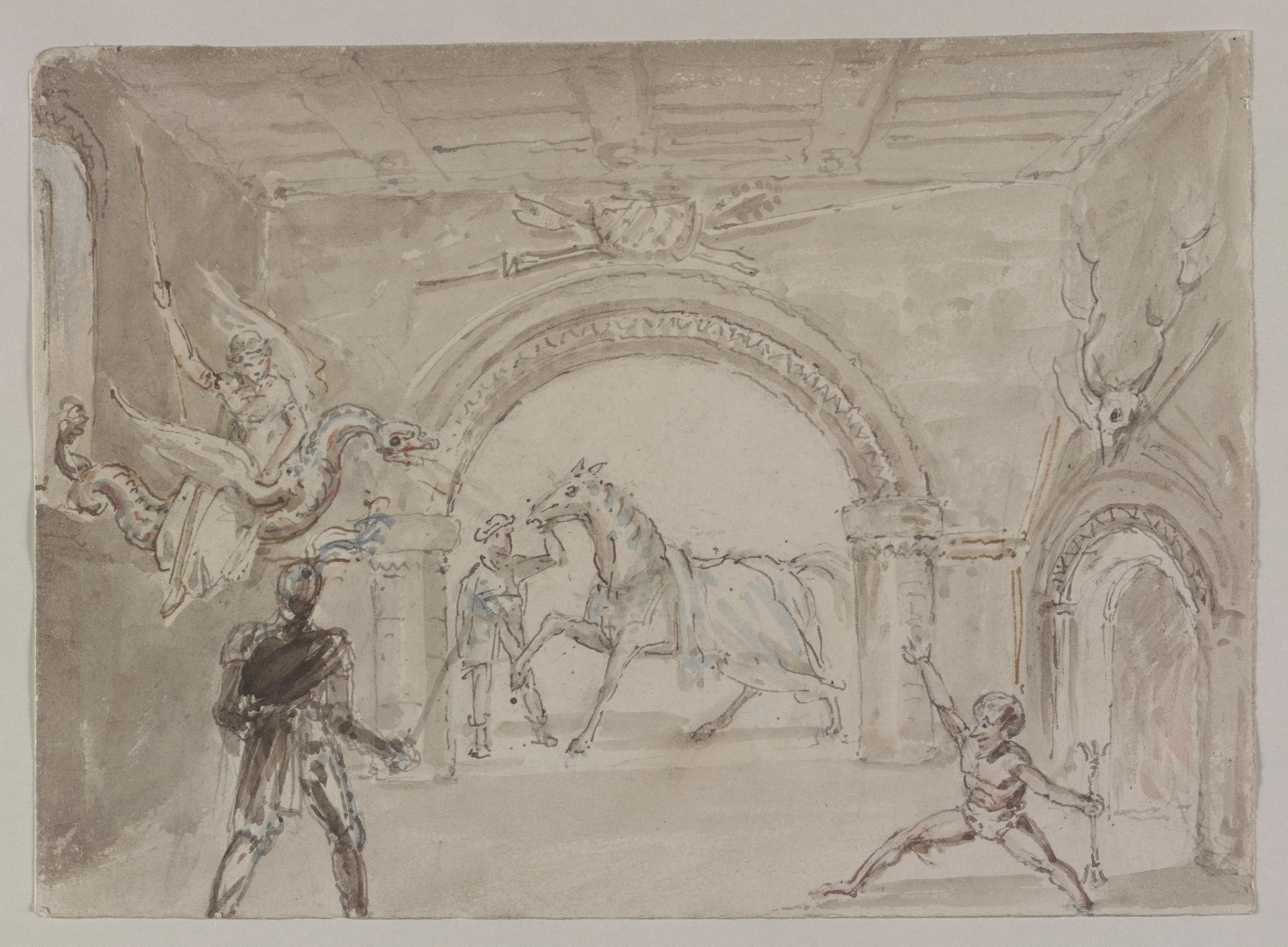

There are different ways to look at the past by means of theatre: you can analyse contemporary productions of plays that are set in the past, such as the reconstruction of King John’s (1166-1216) reign with a contemporary twist in the RSC (Royal Shakespeare Company) 2019 production of Shakespeare’s King John, directed by Eleanor Rhode and with actress Rosie Sheehy in the title role; you can analyse a production staged in the past, such as Charles Kean’s production of George William Lovell’s The Wife’s Secret at the Haymarket Theatre in 1848; or it can be a combination of both approaches: the analysis of a play set and staged in the past, such as William Charles Macready’s staging of Shakespeare’s Henry V at the Covent Garden in 1838. My journey as a theatre historian has led me along the third path.

You may have noticed that two of my three previous examples refer to productions of Shakespearean history plays. That is by no means a coincidence, but an illustration of my own research as a PhD candidate at LUCAS. I look at ways in which the medieval past is recreated on stage in productions of Shakespeare’s history plays in nineteenth-century London. It is an interesting exercise of looking at different layers of “pasts”. As a twenty-first-century cultural historian, I look back at a production from the mid-nineteenth century that looks back at a dramatic text written in the late-sixteenth century, which in turn looks back at the reign of an English king in the Middle Ages. Fascinating, right?

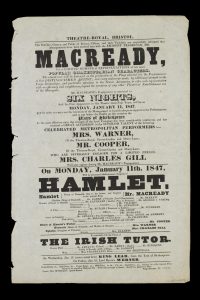

But, you may be wondering, why do I need to reconstruct a theatrical production that happened hundreds of years ago? Indeed, after the curtains are closed, the theatrical event itself is gone. The only way to retrieve it is through reconstruction based on research and a touch of imagination. As I mentioned before, there are different ways to approach the past. Thomas Postlewait explains that these approaches can be understood in a dichotomy between documentary scholarship and cultural history. Other terms used for this dichotomy are positivism versus post-positivism, or theatre history versus performance theory. The documentary scholarship approach is based on archival research, deducing information from material objects, such as promptbooks, playbills, reviews, interviews, diaries, memoirs, letters, etc.

Having a broader scope, cultural history looks beyond the pile of documents, taking into account cultural, social and political contextual information for the performance analysis. The dualism of production-context, however, is too limiting for Postlewait. Instead, he suggests a different way to look at the relationship between performance, archive and the outside world, which works as a guide for my work as a theatre historian.

The model presented by Postlewait identifies four factors that affect the theatrical event: the agents (producers, actors, managers, set designers, etc.), the artistic heritage (the productions staged before and aesthetic traditions), the reception (conditions of perception and evaluation by various people, such as critics, reviewers and spectators), and the world (the various contexts in which the theatrical production is inserted). In the same manner, these four aspects are likewise affected by the theatrical event itself, creating a flow that moves in all directions: between the event and the world, between the world and the reception of the play, between the artistic heritage and the event, between the artistic heritage and the world, and so forth. It is a break with the limiting two-way division between text and context, and the opposition between documentary scholarship and cultural history. The task of a theatre historian is in its essence multidisciplinary.

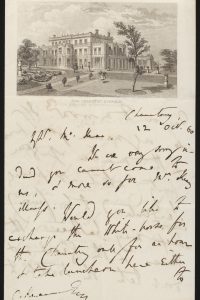

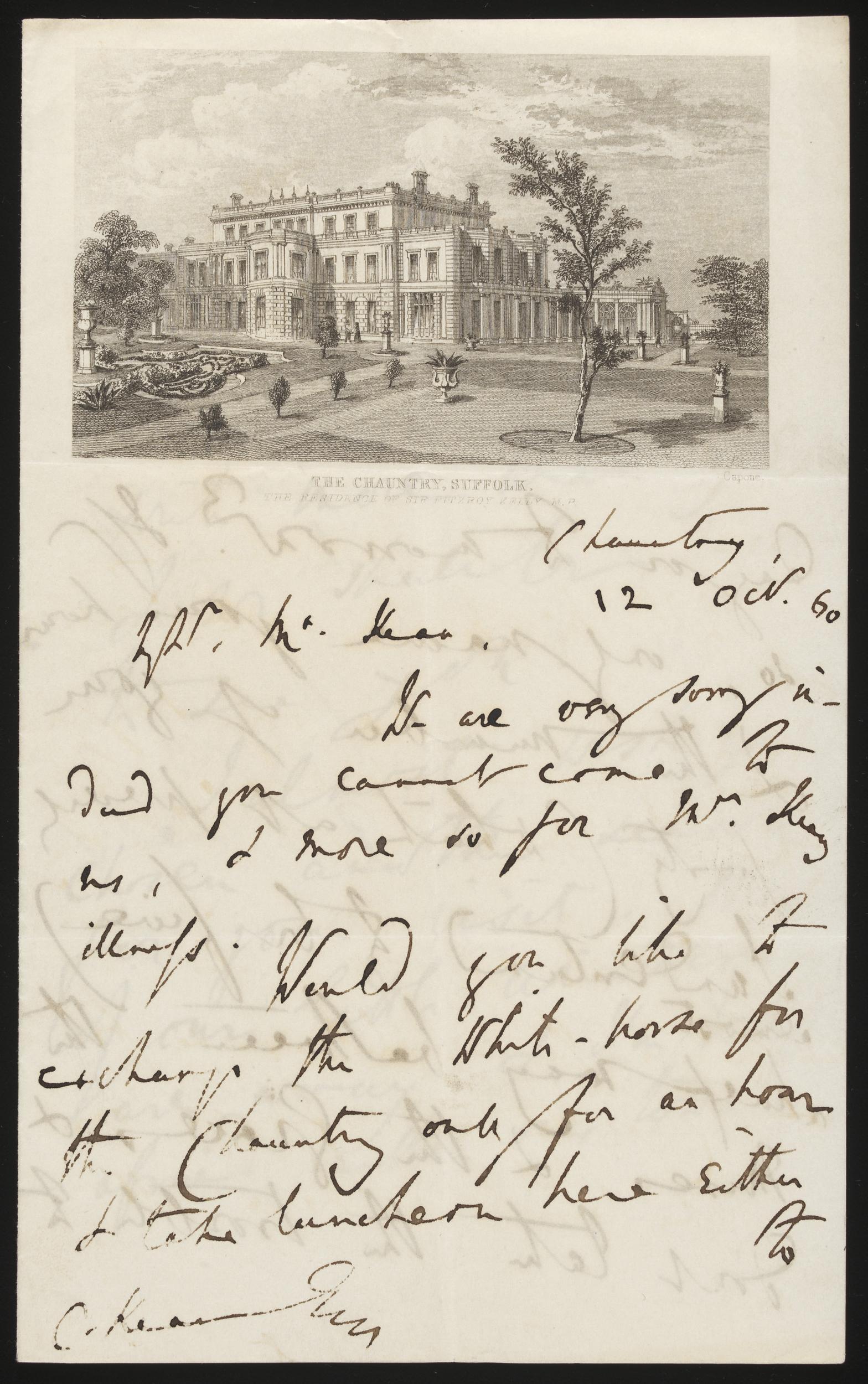

We theatre historians must plunge into the dusty archive of epistles written two hundred years ago, decipher the letters in handwritten promptbooks, read the opinion of a nineteenth-century spectator who saw the production first-hand, and use our mind’s eye to make sense of the material, associating it with the cultural, social and political situation of the moment of production, drawing possible parallels between the world on and off-stage.

To give an example: on the 7th of February, 1601, the followers of Robert Devereux (1565-1601), 2nd Earl of Essex, asked the Lord Chamberlain’s Men at the Globe Theatre for a special production of Shakespeare’s Richard II, first performed years before. The followers had one request: the deposition scene should be staged. In Richard II, the king famously decrowns himself in favour of Henry Bolingbroke, who takes the throne and becomes Henry IV. The Earl of Essex was believed by some to be an appropriate successor to the throne, then occupied by the aging heirless Elizabeth I. Do you think the choice of Essex’s followers to stage Richard II was a mere coincidence? The Earl was executed for treason on the 25th of February, 1601.

I have illustrated how captivating the task of the theatre historian is, and how the theatre offers us ways to look at and understand the past. Next time you go to the theatre, think about this: Why is this play being staged? How can I connect it to the world off-stage? How does it reflect our current situation? If someone has access to this production two hundred years from now, how can it help them understand our world better? It is, indeed, a fascinating subject.

Further reading

Canning, Charlotte M, and Postlewait, Thomas. Representing the Past: Essays in Performance Historiography. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2010.

Moura, F. K. "Charles Macready’s King John: Victorian Theatre and Double-voiced Medievalism." Dramaturgias, vol. 1, n. 1, 2016, pp. 118-127.

Postlewait, Thomas. The Cambridge Introduction to Theatre Historiography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Schoch, Richard. Shakespeare’s Victorian Stage: Performing History in the Theatre of Charles Kean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

© Fernanda Korovsky Moura and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Fernanda Korovsky Moura and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments