Mocking the Monarch: What Do Memes About Queen Elizabeth II Have In Common With Unruly Spectators of Renaissance Spectacle?

If we are to believe the BBC’s laudatory coverage of Queen Elizabeth II’s death last September, all nations of the commonwealth had joined in mournful commemoration of their former monarch. Except not everyone did. Now that the royal mourning period has ended, and the strongest emotions surrounding Elizabeth’s demise have subsided, Bram van Leuveren, historian of early modern diplomacy, rulership, and festival culture, explores what protest against the British monarchy may have in common with sixteenth- and seventeenth-century spectators mocking their ruling elite during ceremonial spectacles of state.

The king is an ass

Propagandists working for rulers across sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Europe already understood that exaggerating public support for their leaders and obscuring information that could potentially damage their public image was crucial for preserving and legitimising power. In commemorative accounts of ceremonial spectacles of state, such as royal entries, weddings, and funerals, propagandists regularly exaggerated the number of spectators present, ignored voices of discontent, and painted an altogether rose-coloured image of the relationship between ruler and subject (Welch 2017: esp. 11-32; van Leuveren, forthcoming (a)).

In the early 1580s, for example, the propagandists of François, Duke of Anjou, published an unprecedented number of books and pamphlets to create the impression that the French duke’s new appointment as overlord of the Netherlands had been met with unrelenting enthusiasm from fêting subjects (Van Bruaene 2007; Thøfner 2007; Peters 2008). In reality, however, his welcome to the Netherlands was not entirely kind-hearted. Among the surviving coins that were distributed around the time of the joyous entries (blijde intochten) of Anjou into Antwerp, Bruges, and Ghent, I found a copper medal that openly ridiculed the duke’s overlordship (see Fig. 1). The obverse of the medal depicted Anjou on horseback, in keeping with his carefully crafted public image as invincible Roman emperor, while the reverse of the object represented the haughty duke as falling from his galloping horse. I currently study these and other medals within the context of my EU-funded research project on Anglo-French tours of the Netherlands between the late 1570s and the early 1640s.

In the early 1610s, the French Bourbon monarchy was faced with similar backlash over ceremonial entries. Ambassadors extraordinary representing Habsburg Spain, Gómez Suárez de Figueroa, Duke of Feria, and Ruy III Gomez de Silva Mendoza y la Cerda, Duke of Pastrana, had entered Paris on various occasions to solidify the double marriage between their crown and that of the French Bourbons (Mamone 1987; McGowan 2016; van Leuveren, forthcoming (a): Chap. 5). But rather than being greeted with due reverence, the Spanish ambassadors were laughed and shouted at by Parisian bystanders. The source of the Parisians’ insolence seems to have been the mount of the foreign visitors, unfamiliar to French eyes. Whereas most European rulers and their representatives were accustomed to perform ceremonial entries on horses, the Duke of Feria and the Duke of Pastrana rode a donkey, which was the preferred mount of Spanish diplomats for peace missions, given the animal’s connotations with Jesus Christ. The latter had also made an entry on a donkey during his famous triumphal visit to Jerusalem.

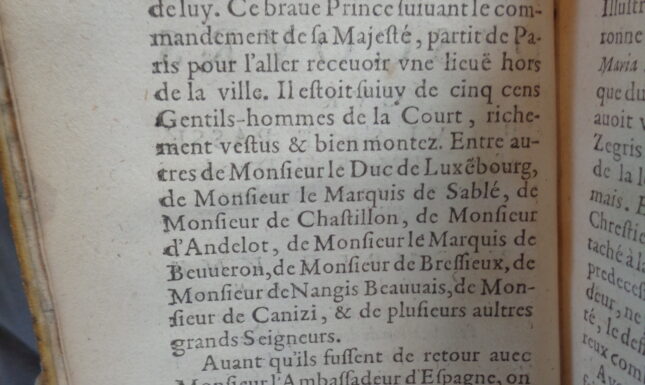

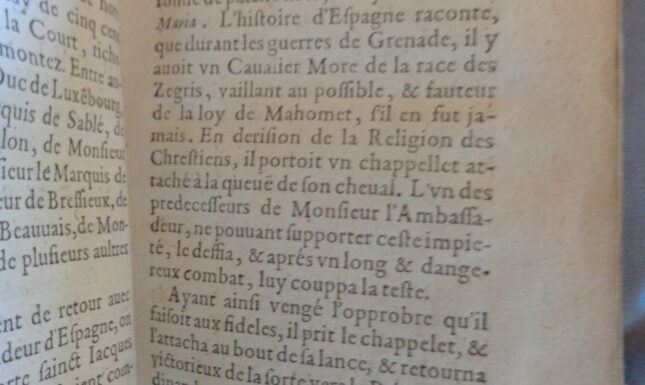

The French king, Louis XIII, was so desperate to please his Spanish allies that after one particularly embarrassing laughing incident involving the Duke of Feria in September 1610 he issued decrees forbidding Parisians to never mock the entry of any Spanish ambassador ever again. The campaign proved futile. In August 1612, when the Duke of Pastrana entered Paris, most citizens burst out into laughter again upon seeing the foreign entourage ride donkeys (van Leuveren, forthcoming (a), Chap. 5). Louis thus quickly granted permission to the publication of a pamphlet which narrated the 1612 entry, obviously leaving out the episode of the insolent Parisians, and including a lengthy explanation of the political significance of the Spanish ambassador’s donkeys, hoping that it would prevent similar incidents in the future (S. D. S. A. 1612: 4-5; see Fig. 2-3). The incidents involving the Duke of Feria and the Duke of Pastrana were narrated in the written correspondence of the English ambassadors to Paris (Hinds 1938: 340, 345, 365).

Louis may have forgotten, however, that rather than mocking the donkeys of the foreign dignitaries, the Parisians had tried to ridicule the king himself, who, in their view, was the real ‘ass’ of the ceremonial entries, since he had been so foolish as to cement peace through marriage with their former foe Spain. I discuss the troublesome entries of the Spanish ambassadors into Paris and other incidents involving diplomatic stakeholders from across late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Europe in my book Early Modern Diplomacy and French Festival Culture in a European Context, 1572-1615, which will appear in the ‘Rulers & Elites’ series of the academic publisher Brill in 2023.

Controlling unruly spectators

The BBC, perhaps not unlike the royal propagandists of old, had skillfully edited their extended footage of the funerary ceremonies for Queen Elizabeth II, and ensuing rituals proclaiming the new reign of Charles III, in a decided effort to leave out voices of protest. Of course, such voices were only to resurface on social media and incidentally in British newspapers and magazines that have traditionally been more critical of the monarchy’s exploits like The Guardian, The Scotsman, and The New Statesman. Several videos appeared on my Twitter feed in which anti-royal protesters in Edinburgh, London, and Oxford, among other cities, were violently arrested or forcibly removed by the local police while holding up signs like ‘fuck imperialism!’ or shouting ‘who elected him [Charles]?’.

Meanwhile, Indigenous communities in Australia protested against the country’s Day of Mourning for Queen Elizabeth on 22 September. They rallied against the British crown and the impact of its violent colonialism on the lives of First Nations Australians today. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the website of the BBC made no mention of the protests and merely referred to ‘the complicated relationship’ that existed between the United Kingdom and Australia, a telling euphemism that brings to mind the attempts of early modern propagandists to whitewash public protest against the crown. On Instagram, finally, I saw footage of Charles’s first official visit to Cardiff on 16 September, during which a bystander firmly reprimanded the newly appointed monarch: ‘While we struggle to heat our homes, we have to pay for your parade. The taxpayer pays 100 million [pounds] for you. And what for? Nid fy mrenin! [Welsh for ‘Not my king!]’.

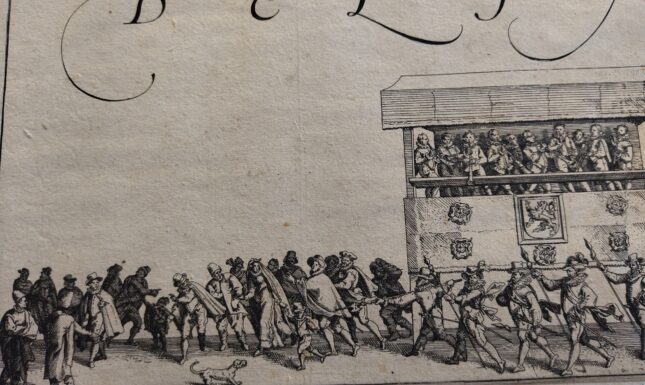

How did early modern monarchies try to control unruly spectators for their spectacles of state? (Kleij and Rush 2022). Openly voicing protest against the crown during such ceremonies or in printed pamphlets issued before, during, or after the event was not without risk and could result into death by hanging if the city’s or monarch’s guards managed to get a hold of you (Duccini 2003: 49-54). In other words, there is a good reason why most of the pamphlets that were critical of the crown’s pageantry, and which feature in my research on diplomatic spectacles in early modern France and the Netherlands, were published anonymously and often lied about the city in which the text was printed to avoid prosecution (van Leuveren, forthcoming (b)). Some of the surviving etchings depicting ceremonial entries in the late sixteenth-century Netherlands offer a glimpse into how civil guards contained general excitement among bystanders of public festivities.

In his series of etchings commemorating the joyous entry of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, into the Hague, on 6 January 1586, Jacob Savery, a Flemish artist, included a print of exhilarated spectators being violently shooed away by the city’s halberdiers (see Fig. 4). The presence of local citizens was vital to the legitimisation of the power structures enacted during any ceremonial entry, but their responses to such events were often difficult to anticipate and control. Similar to the questionable arrests of anti-royalist protesters following the death of Queen Elizabeth, coercion, or even violence, could be used during early modern spectacles of state to prevent further escalation of civil unrest (see Strong and van Dorsten 1964: 37-49 for more on Leicester’s entries into The Hague and other Dutch cities).

On other occasions, there were no bodyguards present to protect the ruling elite from roaring crowds whatsoever. An anonymous pamphleteer revealed that when entering Bourg in October 1615, Louis XIII was not exactly the fearless King of France that he professed to be, but made, in fact, an anxious impression, wearing a harness underneath his costume of a Roman Emperor, fearing that rebellious nobles, who had tried to sneak up on him at every turn and corner in the city, might attack him (anonymous 1615: 4). The relationship between monarch and subject, both today and in the past, is often a fraught one and never quite the ideal marriage as suggested by propagandists of the crown.

Social media protest

Besides shouting or holding up anti-royalist slogans in public last September, protesters rallying against the British monarchy had turned to Twitter to share satirical memes about Queen Elizabeth. The aim of many such memes was to amplify the voices of individuals and communities across the globe whose everyday lives had been, and still were, violently impacted by British imperialism, a colonial project from which the queen herself had benefitted and actively sought to support through a number of symbolic, ceremonial, and diplomatic measures (Satia 12 September 2022; Iyer 17 September 2022). As one Twitter user noted, creating and retweeting memes mocking Elizabeth’s legacy had brought ‘Irish, Indian, Kenyan, Nigerian, South African, and Caribbean [and, I would add, Scottish and Middle Eastern] Twitter’ together (for more on the history of anti-colonial resistance against the British Empire, see Gopal 2019).

The satirical memes excelled in anti-royalist creativity. One Twitter user had overlaid the BBC’s coverage of Elizabeth’s funerary procession with a previous recording of the national broadcaster reporting on a military parade in North Korea, while another had shared a video juxtaposing Star Wars’s ‘Imperial March’ theme with footage of Charles entering Westminster Abbey for his mother’s funeral. The imperialist theme was continued in memes ridiculing the colonial looting of items that are still in use by the British royal family today or are held at museums across the island (see Fig. 5). Other memes mocked the performative reverence towards the British royal family that many institutes in the country, including supermarkets, sport schools, and universities, had adopted in the weeks following the queen’s passing.

How did early modern citizens mock their monarchy in the obvious absence of the World Wide Web? I already discussed the Anjou-mocking medals that were secretly minted for the duke’s ceremonial entries into towns across the Southern Netherlands and the power of crowds laughing at their ruling elite in Paris. There were other options for protest, too. Carnivals, for example, offered effective sites for protest among urban populations that encouraged the inversion of social customs and expectations through public displays of drunkenness, obscenity, and the reversal of social classes and gender roles. The Flemish artist David Teniers the Younger, for one, painted a poignant reversal of elite and non-elite roles in 1630 (see header image). Depicting a group of peasants celebrating the religious holiday of Twelfth Night at a Flemish tavern, the jaunty jester of the company points to ‘the king’ who jugs down a pint of beer while being surrounded by ‘his courtiers’.

Although carnivals rarely had the intention to genuinely undermine social customs and expectations, they could nonetheless inspire civil unrest and uprising against political authorities. For example, a masquerade in Dijon in 1630 resulted into rebellion against royal tax officers, while Shrovetide celebrations in Rouen in 1640 accused the local magistrate of corruption in processions that shockingly mocked the ceremonial entries of ruling elites. Meanwhile, festive societies throughout sixteenth- and seventeenth-century France, known as the ‘Abbeys of Misrule’ (sociétés joyeuses), organised carnivals that openly ridiculed civic authorities (Davis [1965] 1987).

Similar to the powerful mockery of the satirical memes that circulated soon after Queen Elizabeth’s death, the social reversal of early modern carnivals proved a powerful tool for urban populations to claim some form of political agency and hold political authorities accountable for their (mis)rule. Appreciating the early modern history of such derision helps us to recognise the importance of anti-royalist mockery today and the extent to which it may amplify marginalized voices and keep in check those in charge.

I am grateful to Marsh’s Library in Dublin for awarding me a Maddock Research Fellowship in October 2019, which enabled me to read S. D. S. A. 1612, the pamphlet that defended the Duke of Pastrana’s use of donkeys during his ceremonial entry into Paris.

I would also like to thank Andrea Reyes Elizondo from LUCAS for sharing with me her collection of satirical memes on Queen Elizabeth.

Primary references

Anonymous. Ceremonies et Magnificences observees au Mariage de Madame soeur aisnée du Roy, auec le Prince d'Espagne, faict en la ville de Bourdeaux, le Dimanche 18. d’Octobre Mil six cent quinze. Avec ce qui s’est passé de plus remarquable au voyage, depuis Poitiers jusques au depart de Madame vers l’Espagne, Conduicte par Monsieur de Guise, General de l’armée pour le Roy. Poitiers: Jean de Marnes and René Bugeant, 1615.

Hinds, Allen B., ed. Report on the Manuscripts of the Marquess of Downshire, Preserved at Easthamptstead Park Berks. 5 vols. London: His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1924-1988 (1938). iii: Papers of William Trumbull the Elder, 1611-1612.

S. D. S. A. Discours sur ce qui s’est passé à l’arrivee de Monsieur le Duc de Pastrane Ambassadeur d’Espange. Ensemble une resjouissance sur le bonheur des Alliances de France & d’Espagne, avec l’explication d’une Prophetie de Nostra-Damus sur le mesme-suject. Paris: Pierre Bertault, 1612. Marsh’s Library, Dublin, shelf number K2.6.33.

Secondary references

Van Bruaene, Anne-Laure. ‘Spectacle and Spin for a Spurned Prince: Civic Strategies in the Entry Ceremonies of the Duke of Anjou in Antwerp, Bruges, and Ghent (1582). JEMH, 11, nos. 4-5 (2007): 263-284.

Davis, Natalie Zemon. ‘The Reasons of Misrule’. In Natalie Zemon Davis, Society and Culture in Early Modern France, 97-123. Cambridge: Polity Press; Oxford: Basil Blackwell, [1965] 1987.

Duccini, Hélène. Faire voir, faire croire. L’Opinion publique sous Louis XIII. Seyssel: Champ Vallon, 2003.

Gopal, Priyamvada. Anticolonial Resistance and British Dissent. London and New York: Verso, 2020.

Kleij, Sonja, and Kayla Rush, ed. Liminalities, 18, no. 1 (2022), special issue ‘Performance and Politics, Power and Protest’ <http://liminalities.net/18-1/&...> [accessed on 5 December 2022].

Iyer, Aditya. ‘No One Can Force Us to Mourn for the Queen – And That Is a Glorious Thing’. Medium, 17 September 2022 <https://aditya-iyer.medium.com...> [accessed on 5 December 2022].

van Leuveren, Bram. Early Modern Diplomacy and French Festival Culture in a European Context, 1572-1615. Leiden and Boston: Brill, forthcoming (a).

———, ‘Print and Pageantry as Early Modern Tools for Public Diplomacy: French-Language Pamphlets on the Habsburg-Bourbon Weddings (1614-1615) and Marie de Médicis’s Tour of the Low Countries (1638)’. Medievalia et Humanistica, no. 48 (forthcoming (b)), special issue ‘The Transnationality of Early Modern Theatre and Theatrical Events’, ed. by Jan Bloemendal.

Mamone, Sara. Firenze e Parigi. Due capitali dello spettacolo per una regina, Maria de’ Medici. Milan: Amilcare Pizzi, 1987.

McGowan, Margaret M., ed. Dynastic Marriages 1612/1615: A Celebration of the Habsburg and Bourbon Unions. London and New York: Routledge, 2016.

Peters, Emily J. ‘Printing Ritual: The Performance of Community in Christopher Plantin’s La Joyeuse & Magnifique Entrée de Monseigneur Francoys … d’Anjou’. Renaissance Quarterly, 61, no. 2 (2008): 370-413.

Satia, Priya. ‘The British Monarchy Helped Mortgage Our Collective Future’. Time, 12 September 2022 <https://time.com/6212672/queen...> [accessed on 5 December 2022].

Strong, Roy C. and Jan A. van Dorsten, ed. Leicester’s Triumph. Leiden: Leiden University Press; London: Oxford University Press, 1964.

Thøfner, Margit. A Common Art: Urban Ceremonial in Antwerp and Brussels During and After the Dutch Revolt. Zwolle: Waanders, 2007.

Welch, Ellen R. A Theater of Diplomacy: International Relations and the Performing Arts in Early Modern France. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101029762.

0 Comments