MOM 1: In Love with Your Stepmother

23 to 31 March is the Dutch National Week of the Book. For this reason, the month March will be devoted to this year's theme ‘de moeder de vrouw’, as the Month of the Mother (MOM). This week's blog explores a son's problematic love for his stepmother.

From 23 until 31 March, it is the Dutch National Week of the Book 2019. This year’s theme is controversial to say the least: ‘De moeder de vrouw’—‘the mother the woman’ (without the comma!). It is a reference to the title of a sonnet by Dutch poet and essayist Martinus Nijhoff (1894–1953), which he published in his Nieuwe gedichten (1934). Nijhoff describes in a beautiful and timeless way that he went to Bommel to see the bridge. There, he saw a lonesome woman at the steering wheel of a barge. She reminded him of his own mother.

The choice for this Week of the Book’s theme has earned the organization of Stichting Collectieve Propaganda van het Nederlandse Boek (CPNB) a lot of criticism. In an open letter, almost three hundred Dutch authors asked why women should be identified as mother and why two men were asked to write the essay and the book that is distributed as gift throughout the Netherlands during the Week of the Book. Sylvia Witteman (De Volkskrant columnist) wrote on Twitter that she would have liked a woman to write this year’s essay. Author Stella Bergsma proposed to write an alternative essay with the title De vader de lul (‘The father the dick’). The authors Maartje Wortel en Marjolein van Heemstra will organize an alternative literary ball.

In an entirely different way, the connection of mother and woman is problematic. That specific connection of woman and mother without comma suggests an inherent relation between the two. When you are a woman, you are also automatically a mother. But what if it does not? What if being a mother makes being a woman impossible?

Forbidden Desires

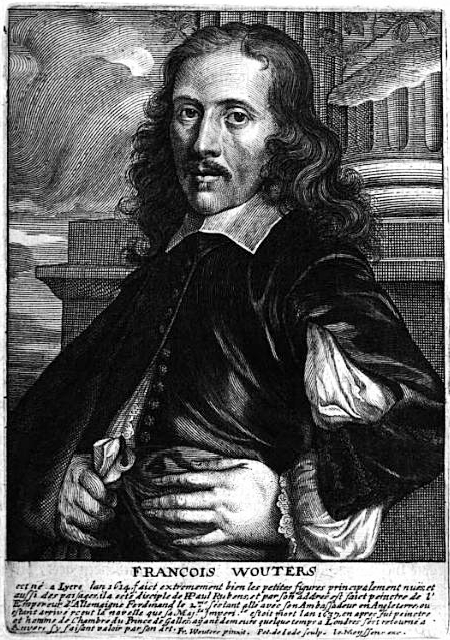

This can maybe be seen best in stepson-stepmother relationships, in which desire is a taboo subject. I will show this through one example from a seventeenth-century play by the Antwerp playwright Anthoon Franciscus Wouthers: De verliefde stiefmoeder oft de gestrafte bloetschandt (1665, ‘The Stepmother in Love or Punished Incest’). The play was an adaptation from the Spanish play El castigo sin venganza (1631, ‘Punishment without Revenge’) by Lope de Vega and, thus, it was naturally a box-office hit on the Antwerp stage.

From the play’s Dutch title, it is already clear how playwright and printer intended to frame the play: as a form of incest. In early modern Dutch and Flemish ordinances, there was an explicit prohibition to have sexual intercourse with your stepmother or stepfather. It actually means that it happened more often, although State and Church regarded it to be a form of unnatural sex and incest. When reading the play, however, something else shows.

The stepmother Cassandra—whose name literally means ‘she who traps men’—urges her stepson Frederico to open up to her. Like in the original, Frederico says that he better remain silent, because that would be less harmful to them both:

Then, Cassandra tells her stepson a story about a prince who also fell in love with his stepmother. Being lovesick, the court physician tried to heal the prince, but only after the stepmother entered court, the doctor noticed that the prince’s face ‘caught a renewed fire’, revealing his love for the woman. Cassandra lets her son know that she sees the same in his case and that she is actually aware of his love for her: ‘Frederico do not lie about that I saw such in your being’ (v. 829). The dilemma is now whether Frederico should and could reveal his passions, or if he should remain silent. That choice itself is torture.

The verbalisation of his feelings involves a real risk for Frederico though. He will experience the consequences of his revelations in the conclusion of De verliefde stiefmoeder, when his father, the Duke, tricks him into killing his own stepmother. Then Frederico is killed by the Marquis of Mantua for killing his stepmother. The Duke never lifts a finger. The Marquis says: ‘Behold a punishment without revenge’. The Duke disagrees, however, saying that he regrets what has passed. He never wanted this to happen as well, but the law forced him to punish both his son and his wife.

It is a sad story with mere losers, a story that elicits compassion. The Marquis closing statement expresses what we can summarize as poetic justice, focussing on the retaliation of incest:

In the eyes of the spectators, however, this could not be poetic justice. Following the plot of the play, instead, the tragic part of De verliefde stiefmoeder is still that neither Cassandra nor Frederico could fulfil their desires. Moreover, their reward for having those feelings in the first place was death. The play focusses on Cassandra’s and Frederico’s tragic love entanglement. To the audience, poetic justice becomes an unsatisfactory solution and that becomes ever more evident taking into account the hate that the audience had for the specific tyrannical manifestation of justice in this play. In other words, public opinion disfavoured the outcome of Wouther’s De verliefde stiefmoeder.

After having witnessed this intricate, pitiful love affair, the Antwerp spectators all wanted to have a stepmother like Cassandra of their own. One laudatory verse says:

Cassandra must have been a commanding and elegant presence according to this testimony. The emotions that Cassandra displayed were positively received, for they represent something different from the hatred and rage that concludes the play.

An anonymous author records, furthermore, that ‘as Frederico and Cassandra make the Theatre echo with applause and lament, the audience celebrates Wouther’s rising star to extremes’ (fol. 3v.). The Antwerp audience seems to have been on the side of Cassandra and Frederico rather than on the side of a society that demanded chaste behaviour of them.

Not the emotions for a stepmother should be tempered, but rather the cultural anxiety about a mother who is also a sexual woman in the eyes of her son. Such cultural anxiety can be found in other writings of the time: the physician Johan van Beverwijck (1594–1647) said in his Schat der gesontheyt (1660, ‘Treasure of Health’) that only God can help in situations where lovesick individuals pursue an incestuous or otherwise forbidden relationship. Trying to cure the ‘disease’ by allowing the consummation of such love would save the body, but it would mean losing one’s soul. On the Dutch-language stage, lovesick patients are negative examples that are to instil fear and compassion in audiences. Clearly, Wouthers’ De verliefde stiefmoeder did something else.

© Tim Vergeer and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to the author and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content

0 Comments