Neptune on the Amstel: Theatre as Public Diplomacy in the Early Modern Netherlands

In this blog, Dr Bram van Leuveren, Marie-Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellow at LUCAS, examines the theatrical performances that Dutch city councils staged for English and French rulers and their diplomats between the 1570s and 1640s.

An illustrious guest

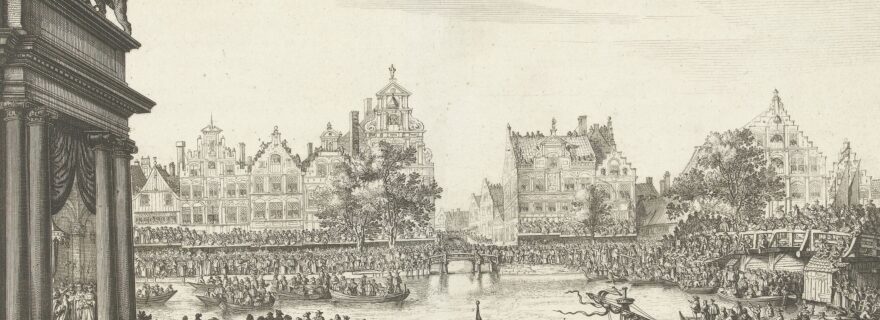

Imagine living in 1630s’ Amsterdam, arguably the wealthiest upstart in Europe at the time. The Dutch East India and West India Companies have already brought the city much economic prosperity and international prestige, owing to their global trade networks and violent colonial exploits in South Asia and South America (Sint Nicolaas et al. 2021). In Fall 1638, the mayors of Amsterdam throw a magnificent fête for the visit of an illustrious French royal: Marie de Médicis, Queen Mother of King Louis XIII of France [fig. 1]. As a respectable burgher, you have bought window space in one the mansions along the Amstel to catch a glimpse of De Médicis, as she cruises the river on a tapestried boat. The streets bustle with excited city folk and foreign visitors. You cheerfully greet your neighbours downstairs, who have brought their own fold-out chairs, and overhear Tyrolian, Swedish, and Polish diplomats converse in Latin [figs. 2-4]. Children have climbed up the trees along the canal, while lovers cozy up on bridges overlooking the scene.

Suddenly a triumphal float appears, as if emerging from the Amstel, featuring a handful of actors disguised as Roman mythological gods. You recognise Neptune, wielding his trident, and Mercury, sporting a winged helmet and fashionable moustache, as well as four water goddesses, who personify the – by then – four known continents, Africa, America, Asia, and Europe [fig. 5]. The city maiden of Amsterdam, played by a young local woman, delivers verses to De Médicis, written by the famous Dutch poet Joost van den Vondel. The verses explain the allegorical meaning of the pageant. Whereas the Queen Mother rules the four parts of the world through her illustrious dynastic connections, Amsterdam makes profit from these parts through maritime commerce, as represented by Neptune and Mercury on the triumphal cart (colonial violence is conveniently ignored here!). From your comfortable window seat, you see the foreign ambassadors downstairs take note: Amsterdam not only markets itself as a mercantile power to be reckoned with, but also invites De Médicis to partner up as a diplomatic ally on the world stage (see Barlaeus 1638: 41-43).

Public diplomacy

Theatrical performances like the mythological spectacle on the Amstel abounded in the official receptions that city councils across the Netherlands organised for prominent royals, nobles, and diplomats from England and France between the 1570s and 1640s. This roughly seventy-year period marked the height of the Dutch Revolt against Habsburg Spain and the latter’s aggressive expansionism in Europe. The urban receptions of the English and French guests, and the festivities staged for them, were primarily held in response to those political developments, as they often addressed the need for interstate peace and collaboration. My Marie-Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship at LUCAS, sponsored by the European Commission, focuses on the public diplomacy of these festive occasions. Political scientists have defined public diplomacy today as the effort of diplomatic actors to influence international public opinion through the use of various media. This effort has been recently discussed within an early modern context by Helmer Helmers (2016), William T. Rossiter (2020), and Klaas Van Gelder and Nina Lamal (2021).

I aim to show that Dutch city councils not only staged pageants such as ballets, mock battles, and dramatic scenes to entertain their English and French guests, but to use them primarily as tools for public diplomacy. In other words, theatre served to manage diplomatic relations between England, France, and the Netherlands, and to represent those relations to a richly varied and international audience. This audience featured rulers, councilors, ambassadors, priests, rabbis, university students, and members of the urban population, including merchants, sailors, shopkeepers, and even mendicants. They would either attend the festivities in person or learn about it in a wide array of printed and visual media, such as commemorative books and medals, which were often commissioned by the Dutch authorities themselves and sometimes distributed among spectators beforehand. I am particularly interested in how these varied individuals, and occasionally the institutions that they represented, reacted to the diplomatic programme of the theatrical performances staged for the English and French visitors, and how the literate among them used the printing press to communicate their own vision of, or participation in, the festive occasions to a larger, sometimes global, audience.

Contesting diplomacies

By taking on board the multiple diplomatic agendas of those who interacted with the Dutch pageants, I seek to complicate the idealised and one-sided vision of the celebrations as provided in the commemorative books of the city councils. My research in archives in the Netherlands, Belgium, England, and France has already demonstrated that Amsterdam’s vision of a diplomatic partnership with De Médicis was not universally accepted and not always considered important by those present or learning about the event in retrospect. For example, many Dutch burgers harboured anti-French sentiments, while the ambassadors of Cardinal Richelieu, Chief Minister of King Louis XIII of France, actively resisted the Queen Mother’s efforts to increase her diplomatic power abroad in the wake of her attempted coup at the Parisian court in 1631. Spanish envoys, on their part, were suspicious of any diplomatic alliance involving the Dutch Republic. Other stakeholders, such as the Jewish community of Amsterdam, effectively used the visit of De Médicis as an opportunity to advance their own diplomatic programme separate from that of the city’s mayors.

Similar tensions and discrepancies in audience reception can be observed in the Dutch welcome of the other English and French visitors and their diplomats that I will study within the context of my research project: Princess Marguerite de Valois, sister of King Henri III of France, Duke François d’Anjou, heir presumptive to the French throne, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester and favourite of Queen Elizabeth of England, Princess Elizabeth Stuart, daughter of King James VI of Scotland and I of England and Ireland, and Henrietta Maria, Queen of England, Scotland, and Ireland. My research on their reception in the Netherlands will reveal that, rather than a modern phenomenon, public diplomacy was central to international relations in the early modern period. Particularly surprising from our twenty-first-century point of view, public diplomacy was directly supported by theatrical performances and the visual and printed media that sought to increase their impact, and the diplomatic agendas of those involved, to the widest international audience possible.

References

Barlaeus, Caspar. 1638. Medicea hospes, sive Descriptio pvblicæ gratvlationis, qua Serenissimam, Augustissimamque Reginam, Mariam de Medicis, excepit Senatvs popvlvsqve Amstelodamensis (Amsterdam: Johan and Cornelis Blaeu, 1638). Leiden University Special Collections. THYSIA 824.

---. 1639. Blyde inkomst der allerdoorluchtighste Koninginne, Maria de Medicis, t’ Amsterdam. Vertaelt uit het Latijn des hooghgeleerden heeren Kaspar van Baerle, Professor in de doorluchtige Schole der gemelde Koopstede. [Translated by Joost van den Vondel.] Amsterdam: Johan and Cornelis Blaeu. Leiden University Special Collections, 12568 D 1.

Helmers, Helmer. 2016. ‘Public Diplomacy in Early Modern Europe’. Media History, 22 (3-4): 401-420.

Rossiter, William T. 2020. ‘“Lingua Eius Loquetur Mendacium”: Pietro Arentino and the Margins of Reformation Diplomacy’. Huntington Library Quarterly, 82 (4): 519-37.

Sint Nicolaas, Eveline, et al., ed. 2021. Slavery: The Story of João, Wally, Oopjen, Paulus, Van Bengalen, Surapati, Sapali, Tula, Dirk, Lohkay. Amsterdam and Antwerp: Atlas Contact.

Van Gelder, Klaas, and Nina Lamal, ed. 2021. Special issue, ‘Cultural and Public Diplomacy in Seventeenth-Century’. The Seventeenth Century, 36 (3).

Further reading

For the fact sheet of my Marie-Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship, see https://cordis.europa.eu/proje....

The Latin original and Dutch and French translations of Caspar Barlaeus’s account of Marie de Médicis’s entry into Amsterdam, which had been commissioned by the city’s mayors, can be accessed at this page: https://www.let.leidenuniv.nl/...

Follow Dr Bram van Leuveren online

Twitter: @bramvanleuveren https://twitter.com/bramvanleu...

Instagram: @bramvanleuveren https://www.instagram.com/bram...

Academia.edu: https://leidenuni.academia.edu...

LinkedIn: https://nl.linkedin.com/in/bra...

© Bram van Leuveren and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2021. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Bram van Leuveren and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101029762.

0 Comments