Open Science: A Necessary Call for Action?

The EU member states’ ministers for research and innovation unanimously signed the Amsterdam Call for Action on Open Science in May. Proponents claim that mandatory open access policies champion the general public’s interests. But is that really the case?

On 27 May 2016, Dutch secretary of state Sander Dekker celebrated the unanimous acceptance of his proposal Amsterdam Call for Action on Open Science by the other EU ministers responsible for innovation and research. Following the conference, the EU issued an elated press statement, proclaiming that ‘the time for talking about open access is now past. With these agreements, we are going to achieve it in practice.’ Carlos Moedas, European Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation, reportedly called the proposal ‘a life-changing move’.

‘Free’ as in ‘free lunch’, and ‘free speech’

The Call’s goals are ambitious: by 2020, all publications based on results of publicly funded research must be freely accessible for everyone. Note that, although this is not explicitly mentioned in the document, ‘freely’ here means both ‘without barriers’ and ‘without payment’. Currently, academic articles are made available to readers via libraries’ subscriptions. If these are to be abolished, this must imply that the publication of academic texts will have to be covered by the creators – the same research institutions, but now as producers instead of consumers.

From the Open Access Button-team, PLoS students, 2015

Research and governments (Netherlands, 2014; U.K. 2012) are not sure if academia will financially benefit from open access: perhaps the publishing costs will not equal the sums now spent on subscription fees, but then again maybe especially EU countries, with their prolific researchers, might just end up spending more on the production of texts than on consumption in the current system. Yet even in that case, the new policy could be worth it, if society at large will benefit, and this is argued by Dekker: professionals, such as teachers and entrepreneurs, could include the most recent knowledge in their work if it’d be openly available. Moreover, the general public would gain access to knowledge that now remains behind paywalls.

From ‘Open Access Explained’, Griffiths University

The justification for business’ free access could be debated: given that the production and dissemination of academic publications will command costs from research institutes, should multinationals and other commercial parties really get access for free? The added benefit for the leisure-reading public is often unquestioned. But let’s look closely: does the public interest justify this solution of forced open access?

Is there a problem?

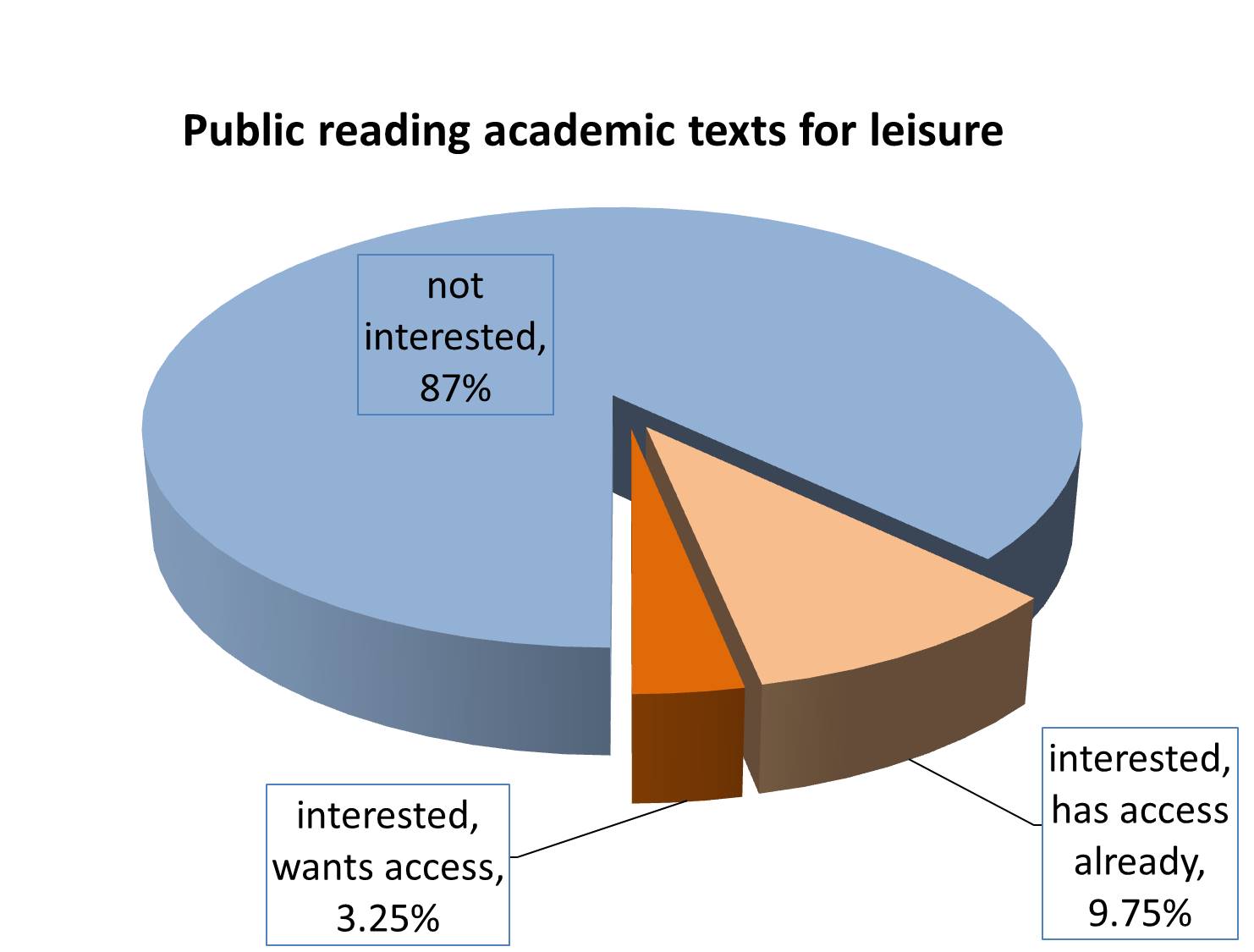

To start on the problem at hand: is the general public widely clamoring for access to research publications? Well, that depends on how you define ‘widely’. The National Library of the Netherlands (KB) and market research agency TNS Nipo investigated the Dutch public’s demand for access to research articles in 2014 via a survey among 44,000 people ages 25 and up. The full research report is – quite ironically, in my view – not openly available, but based on coverage in NRC Handelsblad and in E-Data, we can reconstruct some results. Of all respondents, 13% want to read academic papers, for leisure, work, and/or education. Three quarters of this group already has access to research publications, mostly via employers; some even read more than ten academic papers per year. This leaves 3.25% of the Dutch general audience as a potential target group that is interested in reading academic papers, but currently held back by access barriers.

Illustration of public demand for access to research articles

Medical studies, social sciences and history publications are in highest demand among public readers, according to the report. Critics such as Daniel Allington have convincingly argued that even if these publications would be openly available, their actual readability can be contested: would you be able to digest the contents of (openly available!) articles such as ‘Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events’ or 'Pulse Oximetry: Perception, Pitch, Psychoacoustics, and Pedagogy'?

Existing Alternatives

Most probably wouldn’t, but then, some others might, like 16-year-old Jack Andraka, who invented a cancer detection method by using traditional academic publications. Admittedly,cases like this are cause for optimism about wide accessibility. However, those few truly inspired readers could come by their reading materials in other ways than through a mandatory open access policy. First of all, they could become registered library patrons: EU national libraries and university libraries subscribe to academic journals already, and many offer individual memberships at little or no cost (Leiden University Library: € 30 per year). Granted, that would not make accessibility completely free of individual charge – but neither are other public goods, such as museums and public libraries.

‘Keep calm and open access’ from ‘Beyond the Book’, 2014

Besides access through library membership, the public can already read an increasing number of publications openly online. Canadian researcher Heather Morrison, who has been monitoring the growth of open access for years now, reported that 4,400 open access monographs have now been published, of which 620 in 2016 alone. Besides, the amount of openly accessible content is increasing: the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) and the Electronic Journals Library (EJL), two big aggregators, grow with almost 10% per year. By estimation, that leaves 54 million articles now openly available, many of which are shared in repositories and on social networks like Academia, after having been approved and formalized by academic publishers. These trends show that the publishing landscape is changing already: academics and publishers increasingly seek open access due to existing mandates.

Sign from Vintage Metal Art Store

In the discussions about open access, it is often overlooked that the publication process takes effort and adds value to academic texts, and therefore inevitably merits expenses. A change of business model might nevertheless be worthwhile, but then it needs to be taken into account that the perceived need of the public for access to research is not that large in numbers of readers. It doesn’t seem to be extremely urgent either, given the fact that curious individuals can already become library members, and use the increasing stacks of openly available material. Is the Call for Action on Open Science a life-changing solution, then? From the general public’s point of view, I’m not so sure.

---

Further reading

- Peter Suber offers an excellent, if idealist, Open Access Overview.

- On the many meanings of ‘open’ and ‘ free’, as well as framing used in open access debates, please read Phil Davis’ introductory piece on The Scholarly Kitchen, and the full article ‘How the Media frames open Access’ in the Journal of Electronic Publishing (12.1, 2009).

- There’s much more to say about the current policies around open access, and specifically if you take into account the differences in publication practices between Science, Technology, Engineering and Medicine (STEM) and Social Sciences, Law and the Humanities (SSL&H). A comprehensive pro-OA read is: Martin Paul Eve, Open Access and the Humanities: Contexts, Controversies, and the Future (Cambridge University Press, 2014), which is openly available here. Librarian Jeffrey Beall poses criticism, for instance in this article in Learned Publishing.

- Did you know that the Journal of the LUCAS Graduate Conference, edited by LUCAS PhD students and with contributions from doctoral students all over the world is available in open access too? It is listed in the DOAJ, and an interesting read!

© Fleur Praal and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Fleur Praal and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments