#OTD: Cyclical Experiences of Time in the Digital Age

Today, 3 October, is the official city holiday Leiden's Ontzet. Why do we care so much about anniversaries of past events, and how are they commemorated on digital media?

Today, 3 October, is an important day for the city of Leiden: the official city holiday Leiden’s Ontzet commemorates the anniversary of the liberation from the 1573 - 1574 Siege of Leiden by the Spanish Army during the Eighty Years’ War. In the morning, people traditionally eat herring and white bread, which was supposedly brought into the city right after the liberation.

For people not living in Leiden, 3 October might mark the commemoration of different events. German Unity Day, for example, commemorates the anniversary of German reunification of West and East Germany on 3 October 1990, and Mean Girls Day commemorates a conversation between the cult film’s main character and her crush set on that specific day. Mean Girls Day is a good example of a commemoration that mainly takes place in the digital realm.

Scene from the film Mean Girls (2004).

As a medievalist on Twitter, I often look for ways to share cool facts about my field in an engaging manner. One good way to do this, I have found, is by using the popular hashtags #OTD and #OnThisDay, that are used to share events in history on the date of their anniversary. Twitter accounts like Football On This Day, On This Day She, and New York Times OTD are entirely devoted to posting historical anniversaries related to a specific subtheme. Moreover, websites like https://www.onthisday.com/ provide an overview of historical events for every day of the year, and many websites related to history or the news have an ‘on this day’ page.

The popularity of #OTD suggests that people have a desire to read about things that happened on the date of their anniversary. The fact that French actress Claire Lacombe helped storm the Tuileries Palace in Paris during the French Revolution in 1792 and became subsequently known as “the heroine of August 10th” becomes, apparently, more noteworthy when it is actually August 10th. As editors of the Leiden Arts in Society Blog, we also try to play into this desire, for example by reposting a piece on America’s Great Seal on the 4th of July, and scheduling this very post on 3 October. Moreover, the phenomenon is broader than the internet; for example, some Dutch people like to (re)read Gerard Reve’s book De avonden (The Evenings), set during the last ten days of the year, from 22 to 31 December. The success of seasonal products like pumpkin spiced latte is, I think, albeit less intellectual, related.

Tweet from On This Day She, 10 August 2019.

These phenomena seem to reveal a desire for a cyclical experience of time. The dominant conception of time in our society is linear. In our calendars, for example, we note future meetings an events, and at the end of the year, when the calendar is full, we buy a new one. The pre-printed holidays in our calendars, and the birthday calendars that some people have, are remnants of a cyclical temporality that was far more prevalent in medieval culture, when several temporal systems existed side by side. In his book Categories of Medieval Culture (1972), Aron Gurevich argued that both linear and cyclical conceptions of time operated concurrently, as part of different contexts: agrarian, genealogical, sacral or biblical, and historical.

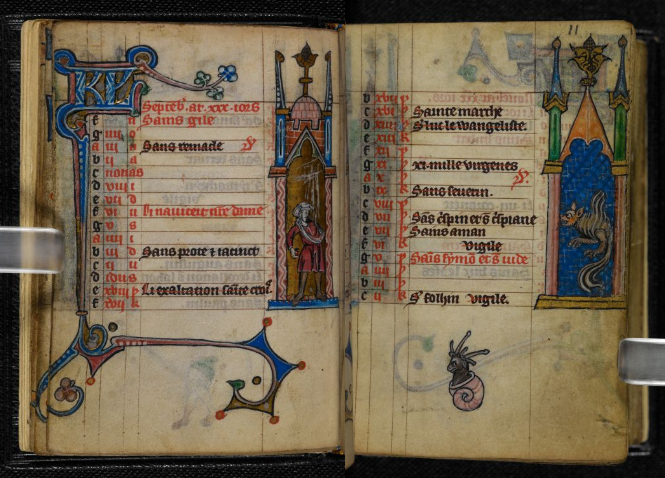

An example of a medieval cyclical experience of times is the liturgical year. This was (and for many still is) a cycle in which people relived biblical events each year in their own time: for example Lent, when Jesus’ forty days in the desert are re-enacted by fasting in preparation of Easter. In the late medieval period, this was not confined to the clergy or only experienced when in church; through Books of Hours laypeople could participate in the liturgical year and week as well. Prayer books included saints’ calendars, and provided prayers for specific days of the week – for example on the Passion of Christ on Fridays. Thus, medieval people were deeply aware of the cyclical nature of time, and anniversaries of past events were important parts of their daily lives.

Calendar of Saints: the months of September and October, with entries like the Nativity of Mary and Luke the Evangelist. Maastricht Hours, 14th century. London, British Library, Stowe MS 17, fols 10v-11r.

The medieval conception of time is central to Carolyn Dinshaw’s book How Soon is Now? (2012). She explores non-linear conceptions of time and different ways of ‘being in time’ in medieval texts, calling these temporalities queer, in the sense that they are engagements with time out of the ordinary. In addition, she examines the engagement with those medieval texts by nineteenth- and twentieth-century amateur readers. Dinshaw sees queer temporality as a characteristic of those amateur readers, people engaging with history in a nonprofessional manner:

Amateurism is bricolage, bringing whatever can be found, whatever works, to the activity. And even as it acknowledges many possible ways of proceeding rather than just one, it also values particularity over generality; it is sui generis, not intended to replicate itself in other activities, that is, in a field.

Amateurs can, according to Dinshaw, be seen as queer because they stand outside the culture of professionalism, having a more intimate connection with the past (note that the word ‘amateur’ come from the Latin verb amare, meaning ‘to love’).

Carolyn Dinshaw, How Soon is Now?

The success of the hashtag #OTD and the corresponding desire for a cyclical experience of time reveals a non-normative way of being in time. It allows not only for a connection with the historical past, but also with one’s personal past; by repeating anniversaries yearly, they become a layered experience, in which not only the past event but also the past anniversaries are remembered. Although academics participate in #OTD, it is part of a wider culture in which amateurs can and do play a role. It does not demand a big time investment or specialized historical knowledge, it is always particular and does not need to bring a field forward. It can have an emancipatory function; by adding the hashtag to facts about historical people or events that are less known, as On This Day She does for women’s history, they can reach a wide audience. It is interesting that this (for the West) pre-modern conception of time is facilitated by digital media; the modern makes the past more present.

Further Reading

Carolyn Dinshaw, How Soon is Now? (Durham 2012).

Aaron J. Gurjewitsch, Categories of Medieval Culture (London, 1985; first published in Moscow, 1972).

© Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments