Rumor or Reality? Moscow Conceptualism as a Challenge for our Contemporary Art Canon

What is Moscow Conceptualism? A late Soviet art movement that is part of our contemporary art canon or a rumor? Cultural historian Dorine Schellens sheds light on this question by looking at the interconnection between academic and artistic worlds.

Analyzing the reception history of a historical figure or cultural artifact can sometimes feel like writing a detective novel – albeit one with footnotes. This is certainly true in the case of an artist group known as the Moscow Conceptualists, whose history and canonization I studied in my PhD thesis. Their story is not a straightforward one. In the 1970s and 1980s, the concept of Moscow Conceptualism, designed as a counterpart to conceptual art movements in the U.S. and Western Europe, came to be associated with the activities of a heterogeneous group of artists, among them painters, poets and performers, who were part of the so-called unofficial Moscow art scene. The common element in their vast and varied work is the playful investigation of Soviet iconography and communist ideology through conceptual or pop art techniques – the images in this text will give an impression of this. However, tracing the exact origins and definition of the term Moscow Conceptualism is tricky. Upon asking, every artist will tell you a slightly different story about its genesis and meaning. To add to the mystery, several of them claim to be the original inventor of the term, while others describe the entire phenomenon as a phantasy or a postmodern practical joke.

Dmitrij Prigov: Pamjat’/Memory (1987).

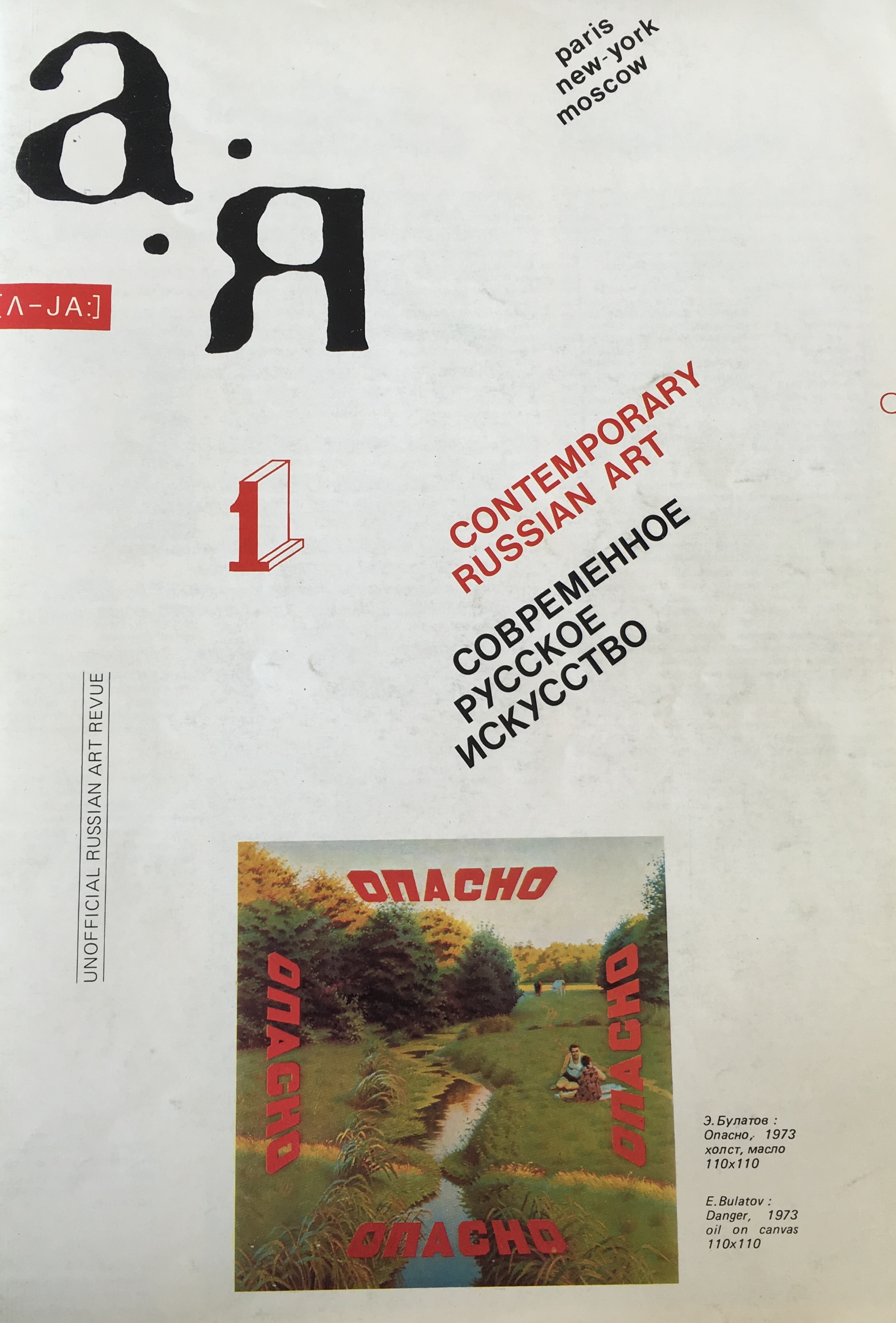

It got even more complicated when one of the main theorists of the group, the well-known philosopher and cultural theorist Boris Groys, described Moscow Conceptualism as “a rumor, a supposition, a suspicion”. “To create an archive for such a movement and to document it”, he stated in an article from 2003, “is to invent it”.[1] This is a quite a provocative statement given the fact that Groys wrote the founding article on Moscow Conceptualism in 1979, which was published in the magazine A-Ja. Contemporary Russian Art [1979–86], a self-edited journal run by an international circle of Russian émigrés who wanted to create a space for independent art criticism and exchange between artists unavailable in the Soviet Union.

The first issue of the magazine A-Ja. Contemporary Russian Art, URL: https://museum-az.com/en/news/pereizdanie-zhurnala-a-ya-sovremennoe-russkoe-iskusstvo/.

Despite the journal’s attempt to introduce Moscow Conceptualism to a wider audience, the artists remained little known in the years that followed, as they were not allowed to publicly exhibit their works neither in the Soviet Union nor abroad. The lack of access and knowledge about the alternative Soviet art scene explains the modest start of the group’s international reception between 1970 and 1985. The story behind the few exhibitions that did happen in this period displays all the elements of a Cold War thriller, with artworks being smuggled in suitcases of scholars and diplomats visiting Moscow and fierce outcries appearing in the Soviet press as soon as these pieces were shown to an audience abroad. With the advent of perestroika, however, the situation changed drastically. As art collectors and curators from abroad gained access to the Soviet art scene, Moscow Conceptualism turned into a downright hype: the artworks’ combination of ‘exotic’ Soviet imagery and ‘familiar’ conceptual and pop art techniques proved to be hugely popular with an international audience. Since then, countless exhibitions and publications have been devoted to the artists, who today represent the canon of contemporary Russian art.

Erik Bulatov’s painting Opasno (1972–73), which depicts an idyllic nature scene framed by the word ‘danger’ (‘opasno’). 1972-1973. Oil on canvas. Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photograph: Peter Jacobs.

So what is Moscow Conceptualism? Is it a rumor or a real art movement that so many people today know and admire? This dilemma provides an interesting starting point for a critical inquiry into canon formation and the interplay between art and research. Many different and at times unforeseen factors form the basis for canonization. However, an artwork or artist stands a good chance of being inscribed into cultural memory when academic knowledge production intersects with artistic practice, art management and journalism. When these areas are connected, a broader circulation of interpretation is enabled. In the reception history of Moscow Conceptualism, we see a close link between the academic and the artistic world. Several Soviet art historians who had emigrated to the West as well as some Slavic departments in Western Europe and the U.S. maintained relationships with the alternative Moscow art scene in the 1970s and 1980s. They were not only responsible for the first academic and journalistic publications on the artists’ work, but also acted as archivists, exhibition curators and occasionally even art smugglers, guaranteeing the preservation of many smaller artworks that could be taken abroad in suitcases. Once Moscow Conceptualism was discovered by the international art world, the close connection between art and research remained. We can observe this in exhibition catalogues of the late 1980s and 1990s, which apart from interpretative texts often contain transcripts of interviews or dialogues between scholars and artists and sometimes even examples of the co-production of artworks. The catalogues reveal how meaning is ascribed to the concept of Moscow Conceptualism both on an academic and an artistic level, with many artists taking on the role of interpreters of Soviet art history, referring to themselves as ‘artistic anthropologists’.

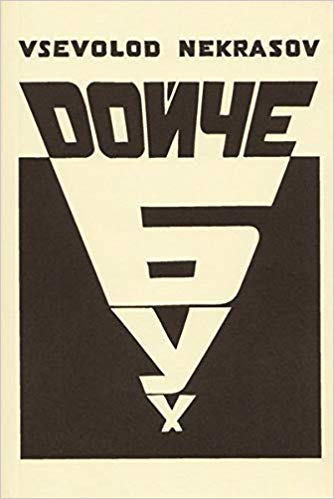

However, not everyone was happy with the way in which Moscow Conceptualism was canonized. One of the most vocal critics was the poet Vsevolod Nekrasov (1934–2009), who wrote a polemic text entitled Dojče Buch/German Book (2002), in which he accused some of his fellow artists as well as the “mafia of Slavists”,[2] as he so unequivocally put it, of misinterpreting the Moscow Conceptualist scene, of which he considered himself a part. He ended his polemic by stating that he would not allow any of his work to be published until his views on the matter were disseminated to the broader public as a counter-narrative to the dominant interpretation created in exhibition catalogues. In other words: canon formation is met with resistance here.

"Vsevolod Nekrasov’s polemic text Dojče Buch/German Book (2002) with a cover design by Erik Bulatov. Published by Edition Aspei, Bochum.

So what is Moscow Conceptualism: rumor or reality? In my opinion, it is both. It is a term around which a history was constructed as a way to interpret certain trends in the alternative Soviet art scene. It is precisely because of this tension that the story of Moscow Conceptualism offers fascinating insights into the process of canon formation and the interplay between academic and artistic knowledge production. Not unlike detective work, it is our job to retrace as well as critically investigate the history of ideas about the cultural past.

[1] Boris Groys, “The Other Gaze: Russian Unofficial Art’s View of the Soviet World,” in Postmodernism and the Postsocialist Condition. Politicized Art under Late Socialism, ed. Aleš Erjavec (Berkeley/Los Angelos/London: University of California Press, 2003), 55-89, 87.

[2] Vsevolod Nekrasov, Dojče Buch. Der Eifer der Kunst des Nichtseins oder Chronik mein-deutscher Beziehungen der Reihe nach, ed. Günter Hirt/Sascha Wonders (Bochum: Edition Aspei, 2002), 45. [“Slawistenmafia”, translation by the author]

Visual Arts, Arts and Society, Canon and Cultural Memory, Soviet Art History, History of Ideas

© Dorine Schellens and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Dorine Schellens and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments