Strange Strophes: Rebellious Singing in Heynck’s Veranderlyk geval

In this blog post, Tim Vergeer tries to discover the melody of one of the songs in Veranderlyk geval, which was the most popular adaptation of a Spanish play in the Dutch Republic.

Veranderlyk geval, of stantvastige liefde (‘Changeable Fortune, or Constant Love’) by Dutch playwright Dirck Pietersz. Heynck premiered on 12 March 1663. It was an instant hit. The play was a perennial favourite and it lists number 3 in the top 50 of plays performed in the Amsterdam Public Theatre (‘Amsterdamse Schouwburg’).

The play’s popularity was not without reason. Heynck had, in his own words, made a rhymed adaptation of an original Spanish play, ‘sometimes doing what I then thought proper; not so much overseeing a precise reproduction, but according to [the customs of] our present-day theatre, making it appear somewhat agreeable in the eyes of the spectators’ (Heynck 1663, fol A2v.).

Fig 1. Title Page of the 1701 edition of Veranderlyk geval. Amsterdam University Library.

Heynck’s play is an adaptation of Mudanzas de la fortuna y firmezas del amor (1649) by the Spanish playwright Cristóbal de Monroy y Silva, which the Dutch playwright changed to cater for the tastes of a sybaritic audience. He was aware of the current fashions and actively applied them in his master piece. Evidently, the play did not meet any of the agreed-upon rules of playwriting.

Of all the changes, especially the songs in Veranderlyk geval are intriguing. There are nine in total, many more than in any other Dutch play. Even more extraordinary is that one song, which is performed in the middle of the third act, is used as a voice for rebellion: one of the two protagonists, Margareta, rebels against the impossibility to meet with her boyfriend, who was taken away to court by the King (who needed an heir and found his long lost son on a farm; he was, however, Margareta’s fiancé). Now she is considering to go to court to be with her partner, despite the King’s injunctions against this. She relates her feelings through a very emotional song:

NU dat de goude zon vertrekt,

En ’t aartryk zich met nev’len dekt,

En geeft de zilv’re maan ’t gewonelyke teeken,

Die op haar beurt en na haar plicht,

Den Hemel met een helder licht

Van duizent fakkelen zo cierlyk gaat onsteeken,

Om zo haar broeder, die zy mint,

Met zorg en voordacht op te zoeken,

Tot zy hem ’s morgens weder vint,

Zo derf ik my nu ook verkloeken,

Om mynen Minnaar na te gaan,

Vond ik hem meê gelyk Diaan,

Wat zouw ik vreugt en blydschap vinden!

Ik vond my zelf in myn beminde,

’t Zou hart en ziel noch vaster t’zamen binden.

Bekommert in dees droeve staat,

Heb ik my zelf in dit gewaat

Verandert; want ik kon myn lyden niet meer dragen,

Wyl d’achterdocht, de vrees, en doot,

My dreigden in dees hoge noot,

Doch myn Stantvastigheit en acht geen werelts plagen.

En of ik juist myn Karel niet

En spreek, ’t is my genoeg t’aanschouwen

De plaats daar hy zyn rust geniet;

Zo veel vermach zyn liefde en trouwe

Op my; die tusschen hoop en vrees,

Gelyk een ouderloze wees

Den hemel smeekt met nare klachten,

Daar hy van droefheit schynt te smachten,

Niet wetende wat lot hem staat te wachten.

(Heynck 1663, vv. 941-970)

Both strophes are rather lengthy: fifteen lines each, almost unparalleled in Dutch seventeenth-century song culture, where strophes often consist of four or six lines and can go up to twelve or thirteen at most. This unusual length makes one wonder to what melody the song was sung.

The play’s stage directions do not make mention of a melody. That should not be a problem, since many other songs in Dutch plays were sung to already-existing melodies, so-called contrafacts. It is, therefore, likely that the melody exists elsewhere in a Dutch songbook.

However, most songbooks, including two of the more famous songbooks Amsterdamsche Pegasus (1627) and the Antwerps liedboek (1544) do not include this particular melody. Furthermore, the Dutch database for songs (the Nederlandse Liederenbank) is unable to identify its melody as well. Thus, the precise melody of Margareta’s lamentation remains unclear.

Fig 2. Title Page of Amsterdamsche Pegasus (1627). Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

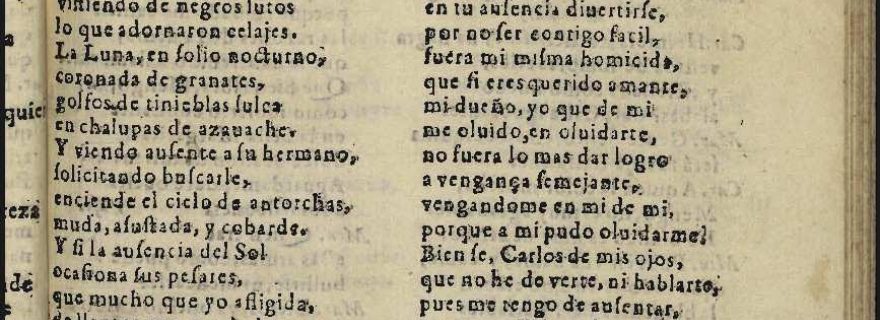

Otherwise, the melody may not even be Dutch, but Spanish. Did Heynck maybe take the melody from the Spanish original? This is sadly also not the case. In Mudanzas de la fortuna, Margareta had re-entered stage ‘as male, with rapier, under cover of night’ (‘de hombre, con espada, y rodela de noche’). However, she does not sing, but she starts a monologue, saying that like the moon, tears confuse her (‘llantos que me deshazen’), jealousy keeps her awake (‘zelos que me desuelan’), and pains fight her (‘penas que me combaten’). If only she could find him. If only he could find her. Being without Carlos is not much (‘estando sin èl, no es mucho’).

The Spanish text is inconsistent at this point. The whole monologue and the next few scenes are written in prose, but still presented as separate verses. What does this mean? It is striking at least that the nightly scenes remain unrhymed. In general, Spanish drama uses polymetric verse, but here it is completely absent.

Fig 3. Folio F8r. from Mudanzas de la fortuna (1649) showing the absence of rhyme. Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid.

Something is happening here, and there is also something strange about the Dutch adaptation. Heynck intensified Margareta’s emotions by turning her words into a song, but he also condensed them, partly also because he summarized the lengthy monologue of eighty lines in the Spanish original into two strophes of fifteen lines each.

It is remarkable that Heynck chose to insert a song at the same specific moment as De Monroy de Silva disrupted his drama. Heynck’s source was a prose translation as delivered by Jacobus Baroces, the Sephardic Jew who delivered Dutch translations of comedias for the Amsterdam Public Theatre with its ongoing need for new material. Did Baroces in his prose translation indicate the rupture in the Spanish text? Or did Heynck see the unusual nature of this passage himself and did he realize its affective potential? Or did he and Baroces converse about the adaptation and how to interpret certain aspects of the text, including the disruption of rhyme in the Spanish original? We cannot know for sure.

Likewise, it is still unclear which melody was used in the Dutch performances. And without the melody a large part of our understanding of the emotional force remains in the dark. Nevertheless, the search for the right melody continues, both in Spain and the Netherlands.

Further Reading

De Monroy y Silva, Cristóbal. Las Mudanzas de La Fortuna y Firmezas Del Amor. In: Doze Comedias Las Mas Famosas Que Asta Aora Han Salido de Los Meiores y Mas Insignes Poetas: Tercera Parte. Lisbon: Antonio Alvarez(?), 1649.

Heynck, Dirck Pietersz. Veranderlyk geval, of Stantvastige liefde: Bly-spel. Amsterdam: Jacob Lescaille, 1663.

Regarding the popularity of Spanish theatre in the Dutch Republic, a few articles are insightful:

Jautze, Kim, Leonor Álvarez Francés, and Frans R.E. Blom. ‘Spaans theater in de Amsterdamse Schouwburg (1638-1672). Kwantitatieve en kwalitatieve analyse van de creatieve industrie van het vertalen’, De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in interdisciplinair perspectief 32.1 (2016), 12–39.

Rodríguez Pérez, Yolanda. ‘“Neem liever een Spaans spel”. Nieuw onderzoek naar het Spaanse toneel op de Noord- en Zuidnederlandse planken in de zeventiende eeuw’, De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in interdisciplinair perspectief 32.1 (2016), 2–11.

On the use of song in theatre, and on the use of song in Spanish theatre, see:

Van Marion, Olga, and Tim Vergeer, ‘Gezongen emoties. Toneelliederen in Rodenburghs Vrou Iacoba bij de opening van de nieuwe Schouwburg’, De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in interdisciplinair perspectief 30.2 (2014), 168–184.

Van Marion, Olga, and Tim Vergeer, ‘Spains Dramatic Conquest of the Dutch Republic. Rodenburgh as a Literary Mediator of Spanish Culture’, De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in interdisciplinair perspectief 32.1 (2016), 40–60.

0 Comments