Suppliers of Beauty. The role of the Dutch art dealer in the nineteenth century

The 33rd edition of TEFAF this month confirms the relevant position of art dealers as important gatekeepers of the art market once again. But what about the early days of this fascinating discipline, did they function as suppliers of beauty or rather as calculated businessmen?

As one of the major international art events The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF) in Maastricht shows the highest quality of art and antiques, covering approximately 7.000 years of art history. Important museums and prominent art collectors belong to the 74.000 annual visitors, so for art dealers the TEFAF could mean the deal of the year. Although the Covid-19 virus prematurely ended the prestigious fair, all eyes were on the developments of the current art market for a while. Although TEFAF emphasizes that art dealers can be seen as important suppliers of art to various museums and collectors, art and commerce are often considered a difficult combination. The discussion about the role of the art dealer as a gatekeeper of the market is not new and was already a hot topic during the mid-nineteenth century, when the interest in contemporary paintings increased in Western-Europe. Important cultural centres such as London and Paris were fashionable cities with the most beautiful galleries, but what about the Dutch art dealers of that time? Which part did they play in the international trade in contemporary art?[1]

The nineteenth century art market

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, a renewed interested in contemporary paintings gradually emerged. This development was to some extend comparable to the flourishing mass market for contemporary paintings between 1580 and 1660 in the Netherlands.[2] During this ‘Golden Age of painting’, economic progress made it possible for a new upper-middle class to surround itself with opulence and various luxurious goods. The nobility had always provided themselves with the most expensive silverware, jewellery and exclusive tapestry. Relatively affordable paintings could be a good alternative for these goods, that were somewhat too expensive for the new middleclass. The absence of an ecclesiastical or royal patron only further facilitated this open art market. As a result, the increasing demand led to a growing supply of contemporary paintings. In order to put food on the table, artists had to act to some extent as real entrepreneurs. They used extensive specialisation in a certain genre, to market themselves as ‘the’ specialist in that field. Although artists initially sold their own artworks, various professions later tried to share in this wealth by trading art in addition to their main occupation. The baker sold local paintings next to his bread and the innkeeper next to his beer. This eventually culminated in the establishment of specialised art dealers.[3]

The following eighteenth century formed a period in which the art trade was mainly focused on old master paintings. The interest in contemporary art only came back sporadically in the first half of the nineteenth century. The ‘collection culture’ that prevailed in the Netherlands at that time was quite important in this respect. As early as the first half of the nineteenth century, the large number of private collectors of contemporary art did not go unnoticed. The Netherlands were for instance significantly described as “le pays des collections”.[4] In addition to that, government policies played an important role in the revaluation of contemporary art. Louis Napoléon Bonaparte (1778-1846), former king of the Netherlands, founded in 1800 the precursor of the Rijksmuseum, the ‘Nationale Konst-Gallerij’, inspired by the Louvre in Paris. More important in this context however, was the foundation of its dependence pavilion ‘Welgelegen’, that mainly focused on a contemporary art collection. Besides that, he initiated the so called exhibitions of living masters (1808-1917) as the equivalent of the Parisian Salons.

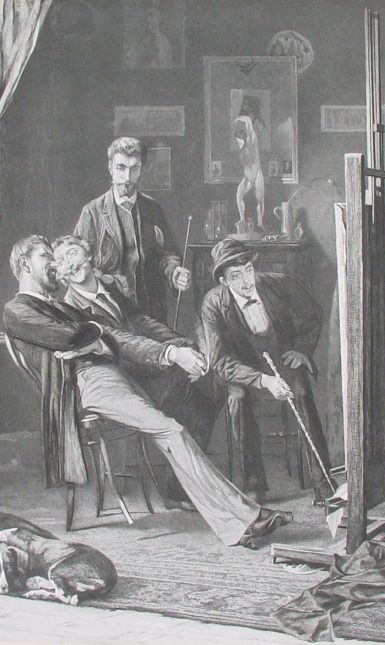

Because of this, the self-consciousness of painters grew and the profession of artist became more accessible. This is why several artist societies were founded during the mid-nineteenth century. The most well-known, that still exist today, are Maatschappij Arti et Amicitiae in Amsterdam (1839) and Pulchri Studio in The Hague (1848).[5] As the members of such a society consisted of both collectors and art dealers as well, membership became an important opportunity for artists to sell their artworks. Exhibitions and so called ‘kunstbeschouwingen’, informal events were paintings and drawings were viewed and discussed, were regular agenda items at those societies. Sales played a more forward role at these events, unlike the exhibition of living masters.

Increasing economic wealth between 1850 and 1910 and a stronger liberal government policy, led to a new buyer audience for luxurious goods such as contemporary art. With the rise of grand department stores, strolling along luxurious shopping windows became a popular activity. International art dealers such as the Dutch branch of Goupil & Cie (The Hague, 1861-1917) and E.J. van Wisselingh & Co (Amsterdam, 1892-1924) established themselves as galleries in posh shopping areas. Between 1850 and 1900, more than 100 specialised art dealers or ‘brokers in contemporary art trade’ were known in Amsterdam and The Hague alone. Art dealers therefore played an increasingly important role. The developments on the art market that had started during the mid-nineteenth century seemed irreversible and formed the basis for the art trade as we know it today.

Ideological art dealer versus the entrepreneurial dealer

With the emergence of specialised art dealerships that traded contemporary art on an international scale, debates about the role of the art dealer flared up as well. Not all artists of that time were positive about the art market. The movement of Eighty, or in Dutch the ‘Tachtigers’, had an extreme aversion towards art dealers and galleries. This group of young painters and poets wanted to create art for its own intrinsic artistic quality, l’art pour l’art, meaning that producing art for a wider public and therefore the market was no option.[6] The only dealers that they were willing to cooperate with, were the so called ‘ideological dealers’. They traded out of love for the arts, rather than for personal profit. The Dutch personification of the ideological dealer were father and son Van Wisselingh. Hendrik Jan van Wisselingh (1816-1884) became known as an ideological art dealer after he tried to introduce the French School of Barbizon in the Netherlands, in a time when there was little to no interest in these type of paintings there.[7] His son, Elbert Jan van Wisselingh (1848-1912), took over his father’s company after his death and moved the business to Amsterdam in 1892. There the gallery E.J. van Wisselingh & Co. became a fact. Just like his father he was seen as an ideological art dealer, since he too financially supported young and yet undiscovered painters, such as the ‘Tachtigers’. Artists as George Hendrik Breitner (1875-1923), Marinus van der Maarel (1857-1921) and even Matthijs Maris (1839-1917) who held a special grudge against art dealers, were willing to do business with Van Wisselingh.

Another reason why Van Wisselingh was considered an ideological dealer, had to do with the fact that he often bought art directly form the artist himself. This was of course more high-risk for the art dealer, than when he would have traded on consignment.

On the other side of the art trade business stood the so called entrepreneurial dealers. They were keen businessmen, who would only trade in art because of the great financial profit they could make out of it. Entrepreneurial dealers would mostly sell what artist and art critic Jan Veth (1864-1925) negatively described as ‘potboilers’, popular works of art such as artworks of the Hague School.[9] This artistical movement consisted out of a group of painters who lived and worked in The Hague, roughly between 1860 and 1890, such as Jacob Maris (1837-1899), Jozef Israëls (1824-1911) and Paul Joseph Constantin Gabriël (1828-1903). The central theme in their artworks was the realistic and typical Dutch landscape, with particular attention to the cloudy skies. Unlike the ‘Tachtigers’, artists from the Hague School were therefore not completely opposed to art dealers. Exemplary for this was the attitude of Hendrik Willem Mesdag (1831-1915) towards the market. The time that he worked for his father's banker's office, before dedicating himself to painting, provided him with a business acumen that he employed throughout his artistic career. Thanks to his extensive network and market approach, Mesdag was able to put himself on the map.[10]

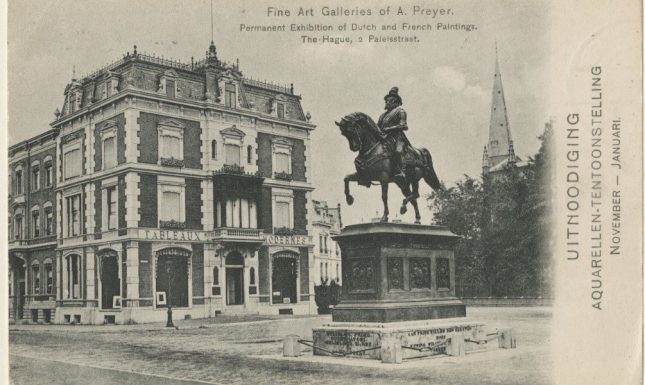

In the Netherlands, the demeanour of the art dealer Abraham Preyer (1862-1927), owner of art dealership A. Preyer (1880-1914), was described as that of an entrepreneurial dealer. This was mainly because he sold very popular artworks of the Hague School on an international scale, preferably to wealthy Anglo-Saxon collectors. However, in reality the distinction between entrepreneurial and ideological dealers was probably less clear cut than often is thought. Most of the art dealers tried to gain a positive reputation by organising exhibitions of artworks by avant-garde painters. On the other hand, in order to maintain good sales, they often sold popular works from for example the Hague School as well. The Amsterdam art dealership Frans Buffa & Zonen (1790-1951) conducted business in this way.

Marketing principles and construction of image

Art dealers of the nineteenth century were already familiar with modern marketing techniques. The Parisian art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922) was one of the first to use a certain marketing strategy in order to increase his sales and to construct a positive reputation as an art connoisseur.[11] Some examples of this are the organisation of (solo) exhibitions, a prominent location of a gallery, preferably near a luxurious shopping area, the publication of a specialist periodical and the use of shopping windows with regularly changing paintings in order to increase the exposure of the gallery’s collection. As an art dealer you could communicate the latter under the guise of ‘art education on the street’. These marketing techniques show that art dealers, even the ideological ones, had to consider contemporary art sometimes merely as their bread and butter. Artists considered art dealers in this context often as necessary evil. Even Van Wisselingh, who was widely considered an ideological dealer, had to make economic decisions sometimes. A typical example of this is the painting by Breitner, that would have looked completely different today if it wasn’t sold by Van Wisselingh.

Breitner considered himself as a painter of ordinary life, or in his own words le peintre du peuple. The city of Amsterdam therefore became his major muse. At one of his paintings of an Amsterdam street scene he depicted a common maid quite present in the foreground.

Critics were not too positive about this composition and because the painting remained unsold for two years, Van Wisselingh gave Breitner 500 guilders to change the canvas to its current state. He had to comply with this request, since he had a business agreement with the art dealer that assured him more or less of a steady income. The ordinary folk woman in the foreground was therefore replaced by an elite lady from the upper class. The adjustment paid off and the painting was relatively quickly sold for 3.000 guilders to a wealthy Amsterdam based lawyer. A few years later, in 1905, the canvas was once again sold by Van Wisselingh for 8.100 guilders, one of the highest amounts for a Breitner ever paid at that time.[12]

Conclusion

The height of the market for contemporary art in the Netherlands was around the last decades of the nineteenth century. This period marked the foundation of the art market as we know it today. Its heyday ended during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Due to an economic decline, partly caused by the First World War (1914-1918), sales of contemporary art fell. The closing of the Dutch branch of Goupil & Cie in The Hague in 1917 marked this tipping point, as well as the fact that the last exhibition of living masters was held that same year. This period however, meant the start of an important role of the art dealer as distributor of contemporary paintings and as gatekeeper of the art market. Their position and reputation came up for discussion and art and commerce are still not considered compatible by everyone. Nevertheless, we can conclude one thing with certainty: art dealers can truly be seen as suppliers of beauty, no matter what motive they have to trade in art. This was not only the case in the nineteenth century, but also on the current art market, as the first days of the TEFAF have shown. After all, it is thanks to the international art trade, that art can inspire globally.

References

[1] This blog is written in response to the current exhibition Suppliers of Beauty. The role of the art dealer in the nineteenth century (February-May 2020) at Pygmalion Gallery in Maarssen, where I acted as guest curator.

[2] Although estimates of production numbers vary, there is a consensus that millions of works must have been involved. For more information, see i.a.: Montias, J.M., ‘Estimates of the number of Dutch master-painters, their earnings and their output in 1650’, Leidschrift, 6 (1990) 3, pp. 59-74; Woude van der, A.M., ‘The volume and value of paintings in Holland at the time of the Dutch Republic’, in Art in history. History in art, Freedberg, eds. D. and Vries de, J., (Santa Monica: Getty Centre for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1991), pp. 285-329.

[3] Boers, M., De Noord-Nederlandse kunsthandel in de eerste helft van de zeventiende eeuw, (Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren, 2012), pp. 16-30 and 50-51.

[4] Marmier, X. Lettres sur la Hollande (Paris, 1841), p. 43.

[5] Hoogenboom, A., De stand des kunstenaars, (Utrecht: Utrecht University, 1991), p. 22.

[6] Jonkman, M., ‘Coleur Locale. Het schildersatelier en de status van de kunstenaar’, in Mythen van het atlier. Werkplaats en schilderspraktijk van de negentiende-eeuwse Nederlandse kunstenaar, eds. Jonkman, M. and Geudeker E., (The Hague: RKD, 2010), pp. 22-27.

[7] The Barbizon School of painters was part of the Realism movement. Artists painted landscapes in the open nature near the French town of Barbizon, close to the Forest of Fontainebleau.

[8] Verberchem [Witsen, W.], ‘Expositie van Wisselingh in Arti’, Nieuwe Gids, 3 (1888), pp. 298-299.

[9] Veth, J. ‘Een zaak van eer’, De Amsterdammer, December 25 1892, p. 3.

[10] Dijk van, M., ‘De mastodont Mesdag’, in Hendrik Willem Mesdag. Kunstenaar, verzamelaar, entrepreneur, eds. Dijk van, M., Jonkman, M. and Suijver, R., (Bussum: Uitgeverij THOTH, 2015), p. 29.

[11] Durand-Ruel Godfroy, C., ‘Paul Durand-Ruel’s marketing practices’, Van Gogh Museum Journal,Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, (2000), pp. 84-89.

[12] Heijbroek, J.F. and Schmitz. E., George Hendrik Breitner in Amsterdam (Bussum: Uitgeverij THOTH, 2014), p. 85.

Further reading:

Alting van Geusau, S., Jonkman, M., Vergeest, A., eds., Schoonheid te koop. Kunsthandel Frans Buffa & Zonen 1790-1951, (The Hague: RKD, 2016).

Dekkers, D., ‘“Where are the Dutchmen?” Promoting the Hague School in America 1875-1900’, Simiolus, 24 (1996) 1, pp. 54-73.

Dekkers, D., ‘“Zeer verkoopbaar” zakelijke afspraken tussen de Hollandse schilder en zijn kunsthandelaar (1860-1915), in Onverwacht bijeengebracht, eds. Jong de, J.L. and Koster, E.A., (Groningen: Instituut voor kunst- en architectuurgeschiedenis, 1996), pp. 33-39.

Galenson, D.W. and Jensen, R., ‘Careers and canvases: the rise of the market for modern art in the nineteenth century’, National Bureau of Economic Research Paper, (September 2002), pp. 3-55.

Hoogenboom, A., ‘Art for the market: contemporary paintings in the Netherlands in the first half of the nineteenth century’, Simiolus, 22 (1993-1994) 3, pp. 129-147.

Heijbroek, J.F. and Wouthuysen, E.L., Portret van een kunsthandel. De firma Van Wisselingh en zijn compagnons 1838-heden, (Zwolle: Waanders, 1999).

Jensen, R., Marketing modernism in Fin-de-Sciècle Europe, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

Stolwijk, C., Uit de schilderswereld. Nederlandse kunstschilders in de tweede helft van de negentiende eeuw, (Leiden: Primavera Pers, 1998).

Thomson, R., ‘Trading the visual: Theo van Gogh the dealer among artists’, Van Gogh Museum Journal, (2000), pp. 28-37.

White, H. and White, C., Canvases and careers: institutional change in the French painting world, (Chicago: University Press, 1993).

© Babette Claassen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Babette Claassen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments