The Descent into Darkness Discovering the Deep-Sea Fauna (1800–1930)

Until the nineteenth century encounters with deep-sea fishes were more or less accidental, but by the beginning of that century naturalists developped an acute awareness that deeper waters house strange creatures...

The Leiden Arts in Society Blog is dedicating a week to fishes and to the exhibition Fish & Fiction which is currently on view at the Leiden University Library. The exhibition is a collaboration between the library and the LUCAS project A New History of Fishes. A long-term approach to fishes in science and culture, 1550-1880. The researchers of this project published a catalogue providing a theoretical background, from which we share content this week. The catalogue: Fish & Fiction. Aquatic Animals between Science and Imagination (1500–1900) can be purchased at the reception desk of the Leiden University Library.

The Copenhagen-based naturalist Peder Ascanius travelled the coast of Norway during the late 1760s, studying the animals living in the country’s many fjords and further out into the Norwegian sea. There were few surprises – the European seas had been well surveyed by that time – but occasionally less familiar creatures would be brought on board. One such enigmatic animal was the so-called rabbit fish (7.1), which instantly strikes anyone who looks at it as something quite out of the ordinary. Its anatomy is unlike that of well-known fish species, and its eerie, ghostly appearance makes it look like something from another world. Its scientific name – Chimaera monstrosa – seems rather fitting.

7.1 | ‘Chimaera monstrosa’. In: Peder Ascanius, Icones rerum naturalium ou figures enluminées d’histoire naturelle du Nord, Copenhague, C. Philibert, 1806, vol. 2, plate 15. [656 A 14]

During the eighteenth century, such encounters with deep-sea fishes were more or less accidental. They included some that swam into shallow waters during the night, dying specimens that drifted to the surface, or sometimes those caught on longlines by fishermen who were trying to catch something else. Nevertheless, by the early nineteenth century these oddities had established an acute awareness among naturalists that only the topmost layer of the seas had been explored, and that deeper waters could house many more of these strange creatures.

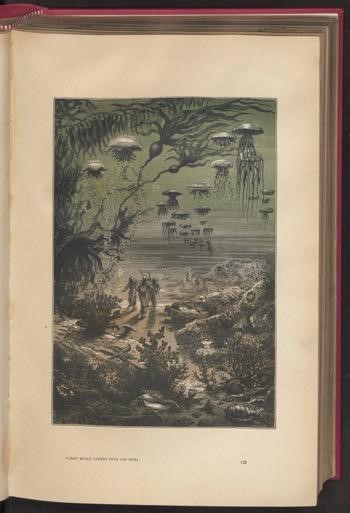

Soon enough people began explicitly looking for deep-sea fishes, bringing up nets from ever deeper regions of the oceans. This did not go unnoticed by the general public: in Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea), published in 1870, the famous French author Jules Verne (1828– 1905) imagined an advanced submarine descending to incredible (and in hindsight not entirely possible) depths. The crew even leave the vessel and walk on the ocean floor. Down there, the sea is shown to be populated by a rich variety of creatures, both familiar and strange, which understandably instil both fear and wonder in the hearts of the submarine’s crew (7.2).

7.2 | Alphonse de Neuville, Crew of the Nautilus. In: Jules Verne, Vingt mille lieues sous les mers, Paris, Hetzel, 1872, p. 125. [3117 A 5]

By the late nineteenth century, the deep sea had firmly seated itself in public consciousness, even though nobody had actually been there, except through imagination. The term ‘deep sea’ now warranted its own entry in encyclopaedias such as the 1897 edition of the popular German Meyer’s Konversations-Lexicon. The image accompanying the rather lengthy article shows a reconstruction of what is taken to be a typical deep-sea fauna. In fact, it is a composite of animals from various geographical areas and depths that had been collected during some of the deep-sea expeditions of the previous decades (7.3). Though they’re not in the centre of the picture, the two luminescent dragonfishes in the otherwise rather dark image immediately catch our eye. This is no accident – of all the odd and surprising things that were found in the dark depths of the oceans, light-producing animals left the most lasting impression.

7.3 | ‘Meeresfauna – Tiefseefauna’. In: Hermann Julius Meyer (ed.), Meyers Konversations-Lexicon. Ein Nachschlagewerk des allgemeinen Wissen, Leipzig-Vienna, Bibliografisches Institut, 5th edition, 1897, part 12. [Museum Boerhaave Library, BOERH g inst 4065]

Challenging the Deep Sea — As so often, it was a somewhat mundane technological development that granted access to the deep sea. For decades, fishermen had been catching oysters and other bottom-dwelling organisms by having their boats drag dredging nets across the seafloor. By attaching such nets to steam-powered vessels, which could drag enormous lengths of cable, much greater depths could be reached. Whereas the 1823 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica held that ‘Through want of instruments, the sea beyond a certain depth has been found unfathomable’, by the mid-nineteenth century several dredging expeditions had sampled the uppermost regions of the deep sea (all well within the so-called ‘twilight zone’, which starts at a depth of 200m and is too dark for anything green to grow, but not entirely dark yet. The subsequent ‘midnight zone’ starts at a depth of 1000m). The British naturalist Edward Forbes (1815–1854) pioneered this technique to great effect, but observed a decrease in animal abundance the deeper he dredged and concluded by extrapolation that there was no life below about 550m.

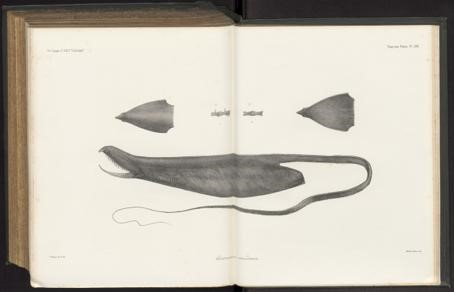

The idea that there was no life at those depths (with the lack of light and monstrous water pressure) was quite popular, though it by no means went unchallenged. The nail in its coffin came with a series of expeditions in the 1860s and 70s, the most important of which was that of the Challenger. H.M.S. Challenger sailed around the world from 1872 to 1876, and made depth measurements and bottom dredges all across the world’s oceans. The Scottish naturalist Charles Wyville Thomson (1830–1882), who was chief scientist on the expedition and had been present on several earlier expeditions as well, wrote in 1873 that ‘Every haul of the dredge brings to light new and unfamiliar forms – forms which link themselves strangely with the inhabitants of past periods in the earth’s history; but as yet we have not the data for generalizing the deep-sea fauna, and speculating on its geological and biological relations; for notwithstanding all our strength and will, the area of the bottom of the deep sea which has been fairly dredged may still be reckoned by the square yard.’ The forms of deep-sea fishes were unfamiliar indeed, perhaps none more so than the pelican eel (7.4), which uses its gigantic mouth to scoop up prey not necessarily smaller than itself.

7.4 | R. Mintern, ‘Saccopharynx ampullaceus’. In: Albert Günther, Report on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of HMS Challenger during the years 1873-76, London-Edinburgh-Dublin, 1887, London etc., Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, vol. 22, plate 66. [3496 B12]

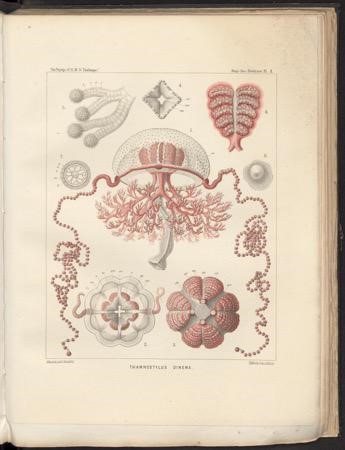

The material gathered by the Challenger’s crew was described in a 50-volume report, edited by Thomson, published during the two decades following the expedition. Apart from physical characteristics of the oceans, such as currents and chemical composition of the water, the report presented to the world several thousand new species, many of which came from greater depths than any known to that date. So rich was the Challenger collection that, for decades, it provided material for other original studies. The famous German naturalist and artist Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), for one, studied, described and drew the Challenger’s jellyfishes, and captured their eerily beautiful shapes in great detail (7.5).

7.5 | Ernst Haeckel, ‘Thamnostylus dinema’. In: Monographie der Medusen, Jena, Fischer, 1881, vol. 2, plate 1. [429 A9: 2]

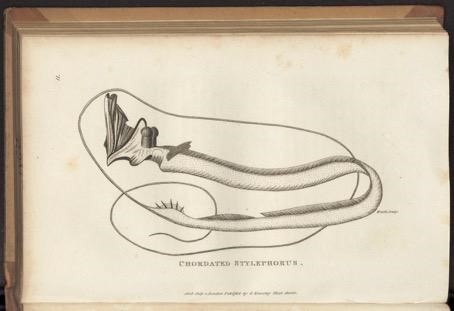

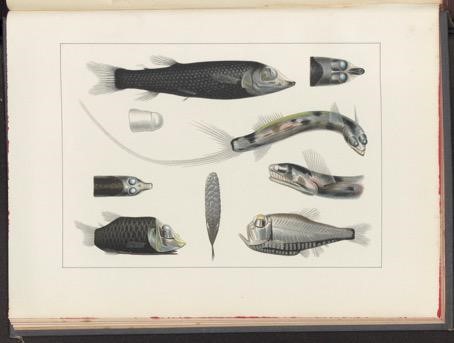

Light in the Darkness — In the decades that followed, many countries wanted their own Challenger expedition. Notable examples include the German Valdivia expedition, which searched the deep regions of the Indian, Antarctic and eastern Atlantic oceans in 1898–99, and the Dutch Siboga expedition, which criss-crossed the seas of the Indonesian archipelago in 1899–1900. By this time the deep sea was beginning to lose some of its mysteriousness, at least to the naturalist, though it was no less strange when compared to other areas of the marine realm. Compare the telescopefish from George Shaw’s 1803 General Zoology (7.6) with those from Carl Chun’s 1900 Aus den Tiefen des Weltmeeres (7.7). Shaw’s fish was a single individual, accidentally caught, probably never seen alive, and it was utterly mysterious to him. Chun, as chief scientist on the Valdivia expedition, had seen multiple live specimens, of several species, and though he had never seen them in their natural environment, they had nevertheless become much more real to him. Accordingly, Shaw’s illustration is somewhat stale and lifeless, whereas the fishes depicted by Chun might just swim off the page.

7.6 | ‘Chordated Stylephorus’. In: George Shaw, General Zoology, or Systematic Natural History, London, G. Kearsly, 1803, vol. IV: Pisces, part 1, plate 11. [641 E 8-11]

|7.7 | Pelagische Tiefseefische mit Teleskopaugen. In: Carl Chun, Aus den Tiefen des Weltmeeres: Schilderungen von der deutschen Tiefsee Expedition, Jena, Fischer, 1903, 2nd expanded edition, opposite p. 576. [KITLV M 3o 110]

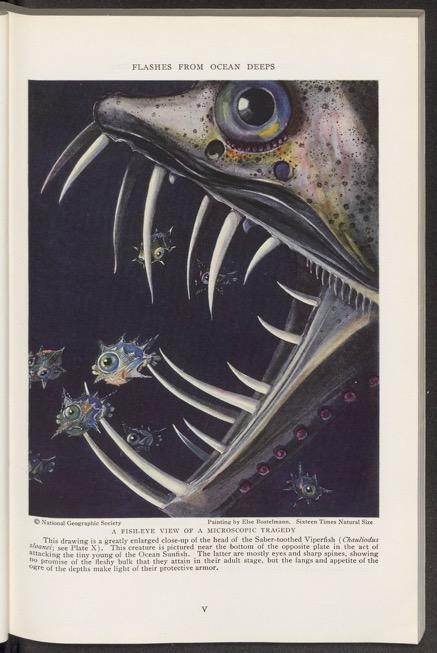

One mystery remained, however, for nobody knew what the deep sea actually looked like, and how the animals there lived, despite brave attempts by artists, like the impression from Meyer’s Konversationslexicon (7.3). It took until the 1930s for Verne’s dream of humans descending to the deep sea to come true, when biologist William Beebe (1877–1962) and engineer Otis Barton (1899–1992) descended to a depth of over 900m. They were lowered into the water in a bathysphere, a spherical steel vessel (barely large enough for two passengers) that was suspended from a ship by means of a cable. Thus, they were the first people to actually observe the animals inhabiting the twilight zone in their natural surroundings, going about their daily business. The expedition’s artist, Else Bostelmann (1882–1961), rendered the animals beautifully and vividly in National Geographic Magazine in 1934 (7.8), bringing to light that which had been hidden in darkness.

7.8 | Else Bostelmann, ‘A Fish-Eye View of a Microscope Tragedy’. In: National Geographic Magazine, 1934, vol. 66, p. 781. [NINO SR k3-4/p1]

Further reading

Beebe W., Half Mile Down, New York, Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1934.

Chun C., Aus den Tiefen des Weltmeeres, Jena, G. Fischer, 1903.

Moseley H.N., Notes by a Naturalist on the “Challenger”, Being an Account of Various Observations made during the Voyage of H.M.S. “Challenger” Round the World in the Years 1872–1876, London, MacMillan & Co., 1879.

Rozwadowski H.M., Fathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep Sea, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press (Belknap), 2005.

Saldanha L., ‘The discovery of the deep-sea Atlantic fauna’. In: K.R. Benson and P.F. Rehbock (eds.), Oceanographic History: The Pacific and Beyond, Washington, The University of Washington Press, 2002, p. 235-247.

Scales H., ‘Illuminations’. In: Eye of the Shoal: A Fish-watcher’s Guide to Life, the Ocean and Everything, London, Bloomsbury, 2018.

Robbert Striekwold and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2018. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Robbert Striekwold and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments