The Omval Defaced: Thoughts on Rembrandt’s Anonymous Interlocutor

This post examines a curious late state of Rembrandt's etching, The Omval—largely dismissed in the literature as a defacement or mutilation of the copperplate—and asks what we might gain from giving it another look.

Printed images—be they woodcut, engraving, etching, etc.—are all products of a process wherein a matrix (a copperplate, woodblock, or other substrate carrying the design) is inked and printed onto a support—usually paper though sometimes parchment or textile. This process can be repeated until the matrix becomes worn down through many runs through a press. The matrix can also be altered many times throughout its life, by several different hands long after the death of its original maker, and these alterations are documented in the successive printings. In print-speak, every time a plate is altered and printed, the resulting impression is a new state of that print.

With this explanation out of the way, I want to talk about Rembrandt’s prints, and the matrices that he used to produce them. Rembrandt often returned to and altered his copperplates between printings, creating successive states that were individually sought after even in the seventeenth-century. His famous Three Crosses was transformed between the third and fourth states in ways that drastically changed the tenor of the scene, and even recast the penitent thief on the right—who initially looked up towards the heavens bathed in a shower of light—as the bad thief enveloped by darkness.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Three Crosses, drypoint on paper, state 3 (of 5), 1653. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. RP-P-1962-39

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Three Crosses, drypoint on Asian paper, state 4 (of 5), 1653. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. RP-P-1962-40

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Omval, etching and drypoint on paper, state 2 (of 3), 1645. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. RP-P-1962-71

Rembrandt van Rijn and anonymous etcher, The Omval, etching and drypoint on paper, state 3 (of 3), c. 1675-1725. British Museum, London. F,5.154 [Creative commons license]

But Rembrandt’s own dramatic state changes aside, I’d like to turn to a print that has long held my interest: the third state of Rembrandt’s etching and drypoint print, The Omval. The first two states show a gnarled tree along a bank of the Amstel, with an amorous pair hidden in the underbrush to the left, and a view across the Amstel to the right. In the third state, large parts of the composition have been overlaid with playing cards: a ten of clubs, a farmeress numbered 5, and a boy blowing bubbles numbered 2. The New Hollstein catalogue raisonné of Rembrandt’s printed oeuvre describes this state thusly:

“The copperplate mutilated by someone who burnished out part of the composition and replaced it with three huge playing cards to create a trompe l’oeil effect. Not by Rembrandt.”

And the British Museum’s website:

“…third state defaced with crude trompe l'oeil-effect playing cards…”

The history of Rembrandt’s printing plates is fascinating in and of itself, but too long and complicated to recount here. In short, even during Rembrandt’s lifetime his plates were changing hands; and in the intervening three and a half centuries those that have not been lost have been reprinted, reworked, cut up, dispersed and otherwise led a life quite independently of their long dead author. One need only look at a comparison of a lifetime-impression of Rembrandt’s portrait of Abraham Francen (fifth-state) and an early nineteenth-century twelfth-state impression to see the how little of Rembrandt’s own hand remains.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Abraham Francen, Apothecary, etching, drypoint, and burin on paper, state 5 (of 12), 1655-9. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. RP-P-OB-534

Rembrandt van Rijn, Abraham Francen, Apothecary, etching, drypoint, and burin on paper, state 12 (of 12), 1655-9. British Museum, London. 1941,0327.11.92 [Creative commons license]

But The Omval’s copperplate was lost long ago, and we only know of its life after Rembrandt via four surviving impressions of the third state, one cropped to remove the playful additions. Two of the four impressions carry a watermark of the Arms of Amsterdam closely related to ones produced in the second half of the seventeenth century, indicating that Rembrandt’s anonymous collaborator was likely working at the end of the seventeenth or beginning of the eighteenth century.

I love thinking about this anonymous maker. Who was s/he? Why did s/he do this? How did s/he come to be in possession of this plate? Was there a market for these prints? I have no real answers for these questions, but I like to imagine our protagonist hard at work scraping and burnishing away the lines of Rembrandt to make room for these stupid and haphazardly etched cards. S/he didn’t even take care to draw cards of a consistent size. There is a strange dissonance in the effort required to remove Rembrandt’s linework and the lack of effort put into the additions. Whatever the motivation, this artist put in some work to realize their vision.

Let’s look again at how the catalogue and museum describe it: Defaced. Mutilated. Both imply value judgements and disfigurement, as if some great crime has been committed against the copperplate; they almost seem to attribute intentionality to this perceived act of barbarism. Perhaps they’re right… But Rembrandt also irreparably altered the copperplate of an earlier artist for his own purposes; was this too a mutilation? A defacement? And besides, I see no ill will in these playful cards, and dismissing the alterations as mere defacement also prevents us from really looking and thinking about what is actually there.

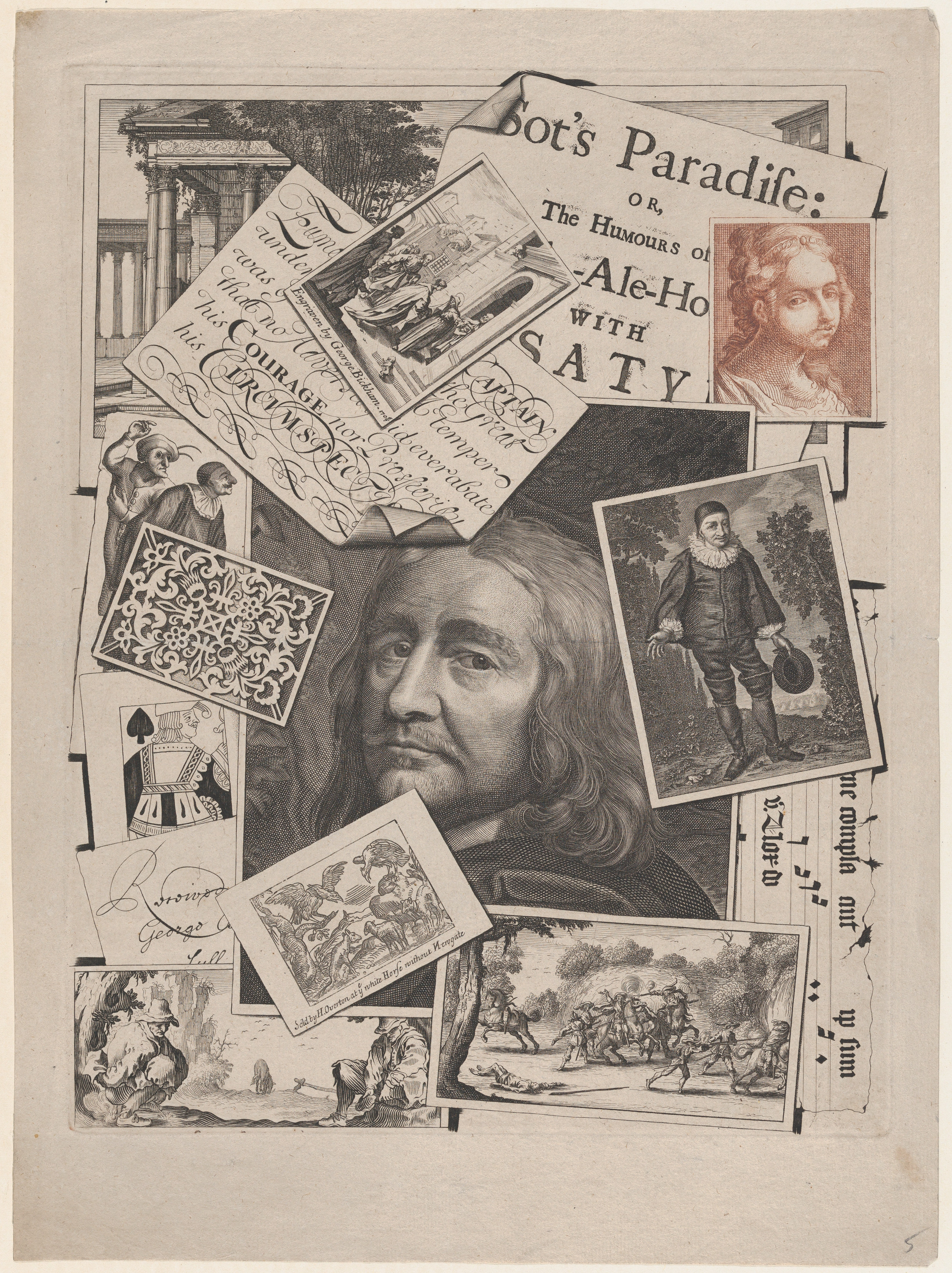

George Bickham, Sr., Medley Print: Sot's Paradise, Etching and engraving, printed black and red ink on paper, 1706–7. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 43.45.25

Trompe l’oeil drawings and prints that emulated overlapping sheets of printed, drawn, and written materials became popular as a genre in eighteenth-century England. These so-called medleys often incorporated imitations of known prints and texts, sometimes slightly altered so that only an attentive and knowledgeable viewer could recognize what was amiss. The earliest printed examples—known as medley prints—date from c. 1706. The genre then spread from England to the Netherlands, France, and Italy throughout the eighteenth century. That the playing cards added to The Omval are in Dutch indicates a Dutch hand etched them, and the watermarks—though not conclusive—point towards a date around the turn of the century, if not earlier. If these alterations were indeed created in the Netherlands c. 1700, it could be not only the earliest Dutch example of a medley print, but perhaps the very first medley print. Moreover, to my knowledge this is the only medley print to actually use a previously published plate as the basis for its design. Unlike all the other practitioners of this genre who incorporated copies of earlier prints int their works, this artist used a ready-made printing matrix itself as a medium. As a result, the play of fictive and real is all the more potent. We do see an actual Rembrandt print before us, but we also see this other hand layered over top of it. However crudely rendered the playing cards may be, they index a palimpsestic collaboration between two artists, and the print thus juxtaposes high and low art, real and unreal, Rembrandt and “Not by Rembrandt.”

Detail of The Omval’s third state.

Hendrick Goltzius (studio), Homo Bulla, Quis Evadet, engraving on paper, state 1 (of 2), 1590. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. RP-P-OB-10.228

There is also the vanitas imagery of the playing card at left. The Leven, or Life card features an infant blowing bubbles beside a vase of flowers and a bowl with smoke rising from it—a common subject called the Homo Bulla, as seen in an earlier print by Hendrick Goltzius. The smoke that dissipates in the air, the flowers that wither with time, the bubbles that last but a few seconds, and the boy’s fleeting youth: all are meant as reminders of the transience of life. The message is now underscored by the fact that playing cards from this period have extremely low survival rates, due to their popular use and low value; such material culture is known as ephemera. One might similarly read vanitas undertones in Rembrandt’s gnarled old tree that dominates the composition, and in the choice of subject: an area of Amsterdam known as the Omval (the Toppling), where ruins once stood. The theme is fitting in that—in addition to etching—Rembrandt chose to work up much of the plate in drypoint, a process by which one digs into the metal with a sharp stylus. Whereas the technique of etching incises lines into the plate with acid, eating away the metal completely, drypoint merely moves the copper around the stylus, creating burred ridges that wear down quickly when printed. Drypoint is thus a more ephemeral print process that yields fewer good impressions; areas that once printed dark and bold are soon reduced to faint lines. Rembrandt, moreover, chose to sign the print in drypoint; with every impression he pulled from the plate, his name faded more and more. By the time our artist acquired the plate, Rembrandt’s name had already faded quite a bit. The plate, separated from (and likely outlasting) its original maker, then became a medium for another artist whose name is fully lost, but whose message of transience ironically persists. Ars longa, vita brevis. Life is short, but art is long.

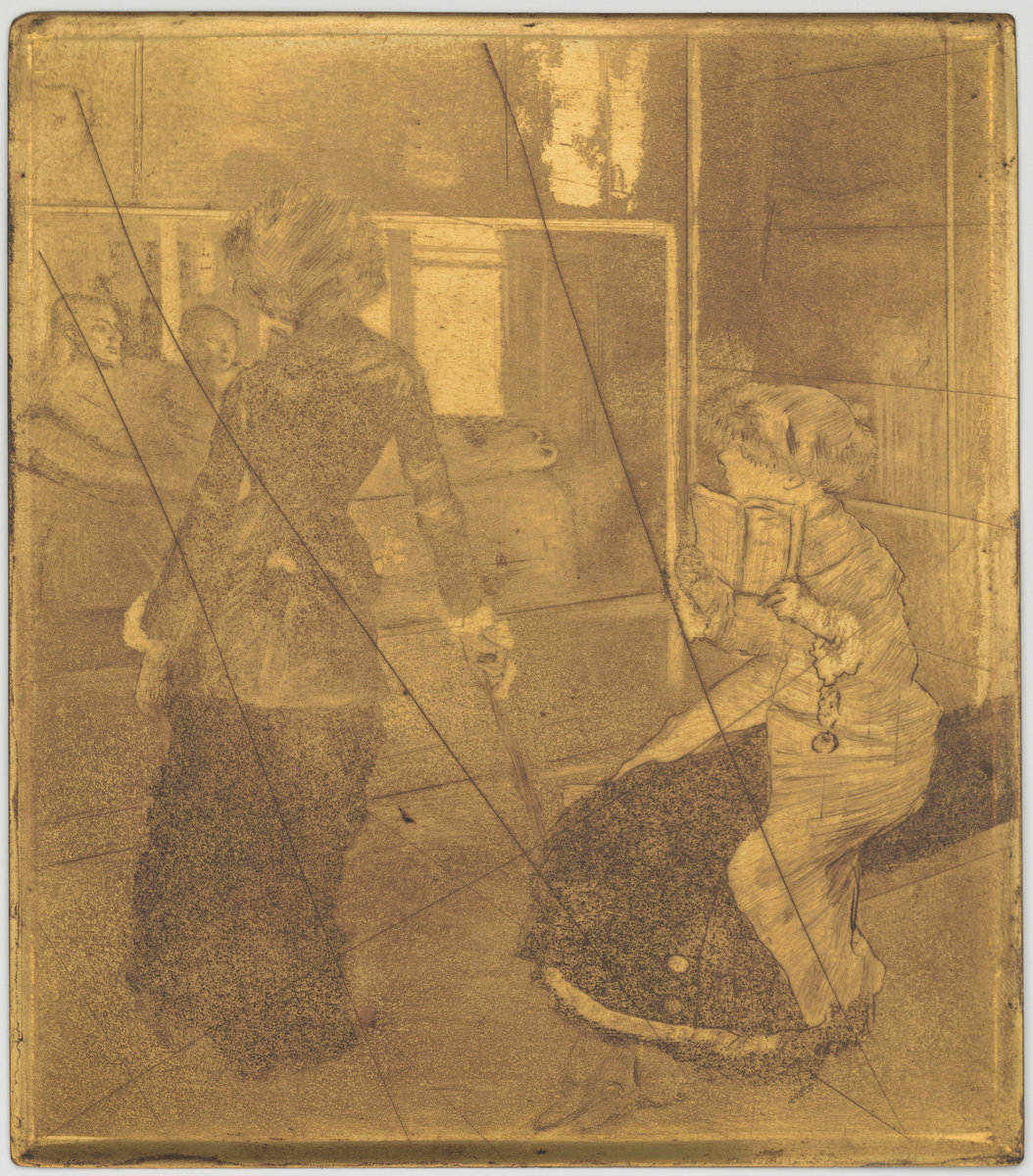

Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery, cancelled copper plate, 1879/1880. National Gallery of Art, Washington. 1995.47.74 [Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon; Open access]

In the late nineteenth century, printmakers began to limit their print editions by defacing their own plates after printing a certain number of impressions, a practice called cancellation. In doing so, they attempted to prevent other printers from getting hold of their plates and printing them ad infinitum. Rembrandt had no such practice, which led to the reprinting and reworking of many of his plates from his time to today. This made his prints more widely available—one can acquire late impressions for relatively cheap—but his hand was also lost in the many reworkings. The Omval never suffered this fate. Impressions of The Omval are consequently less common than his prints that continued to be issued, and all extant impressions (excepting the four with playing cards) carry only the hand of Rembrandt. The unknown actor’s playful contribution effectively cancelled Rembrandt’s plate, preventing further printings and a dilution of Rembrandt’s artistic personality.

So when I look at this print, I think of the diachronic collaboration made possible by the medium of print, and the unlikely bedfellows it brought together. And I like to think our anonymous collaborator—having scraped away a substantial portion of Rembrandt’s work, and having placed these lowly trompe l’oeil playing cards atop it—looked upon their creation with great satisfaction and thought to him or herself: “This is good. This is enough.”

***

This post is thematically related to a session that I am chairing at the 108th annual conference of the College Art Association in Chicago in February, 2020. The aim of the Association of Print Scholars-sponsored session, titled Registering the Matrix: Printing Matrices as Sites of Artistic Mediation, is to examine the lives of printing matrices—woodblocks, etching plates, etc.—independent of their named authors, focusing instead on subsequent alterations by others and the input of printers as collaborators in the artistic process.

Further Reading

Hallett, Mark. “The Medley Print in Early Eighteenth-Century London.” Art History 20, no. 2 (1997): 214-237.

Hinterding, Erik. "The history of Rembrandt's copperplates, with a catalogue of those that survive". Simiolus 22, no. 4 (1993-94): 253-314.

Hinterding, Erik. Rembrandt as an Etcher. Ouderkerk aan den Ijssel: Sound & Vision, 2006.

Hinterding, Erik, Jaco Rutgers, and Ger Luijten. The New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings and Woodcuts: Rembrandt Vols. I-VII. Ouderkerk aan den Ijssel: Sound & Vision, 2013.

© Jun Nakamura and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Jun Nakamura and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments