The Personal Tragedy of the Popular Theodore

Theodore Rodenburgh (1574-1644) was an overly productive playwright whose plays were exceptionally popular. Nonetheless, he was discredited by fellow playwrights and critics, and was denied a place in Dutch literary history. Why is this?

As part of the NWO subsidized project The Theatre of Emotions: Spanish Drama in the Seventeenth-Century Low Countries, I discuss Rodenburgh as the essential and crucial mediator of Spanish culture in the Netherlands. However, he is hardly known by the Dutch.

He could have become one of the foremost authors in Dutch literary history. He was an overly productive playwright and his plays were exceptionally popular among the Amsterdam population. Despite all this, Theodore Rodenburgh (1574-1644) has been discredited during and after his lifetime. What made his fellow playwrights and especially the nineteenth-century critics revile him so much though?

Theodore was born from a distinguished and wealthy family of Protestant merchants from Amsterdam. Exiled to Antwerp during the Dutch Revolt, the Rodenburgh family returned to the city after the Amsterdam Alteration of 1578. The city was now firmly under a Protestant administration and it supported William of Orange against the Spanish ‘yoke’.

Portrait of Theodore Rodenburgh dressed in Spanish fashion (source: Beeldbank Amsterdam)

Theodore was likely groomed to take over his father’s cloth business, but he preferred a career as a diplomat. During his life, we find him across Europe serving the interests of trade companies, the Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, and the King of Denmark.

His mission as an envoy extraordinary to King Philip’s III court at Madrid from 1611-1613 on behalf of the Guinea Traders’ Company was the most important impulse for his literary career. There he must have visited the overcrowded corrales de comedias of Madrid, the local open theatre houses, where he saw the plays of the ‘ingenious phoenix’ Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio (1562-1635) performed.

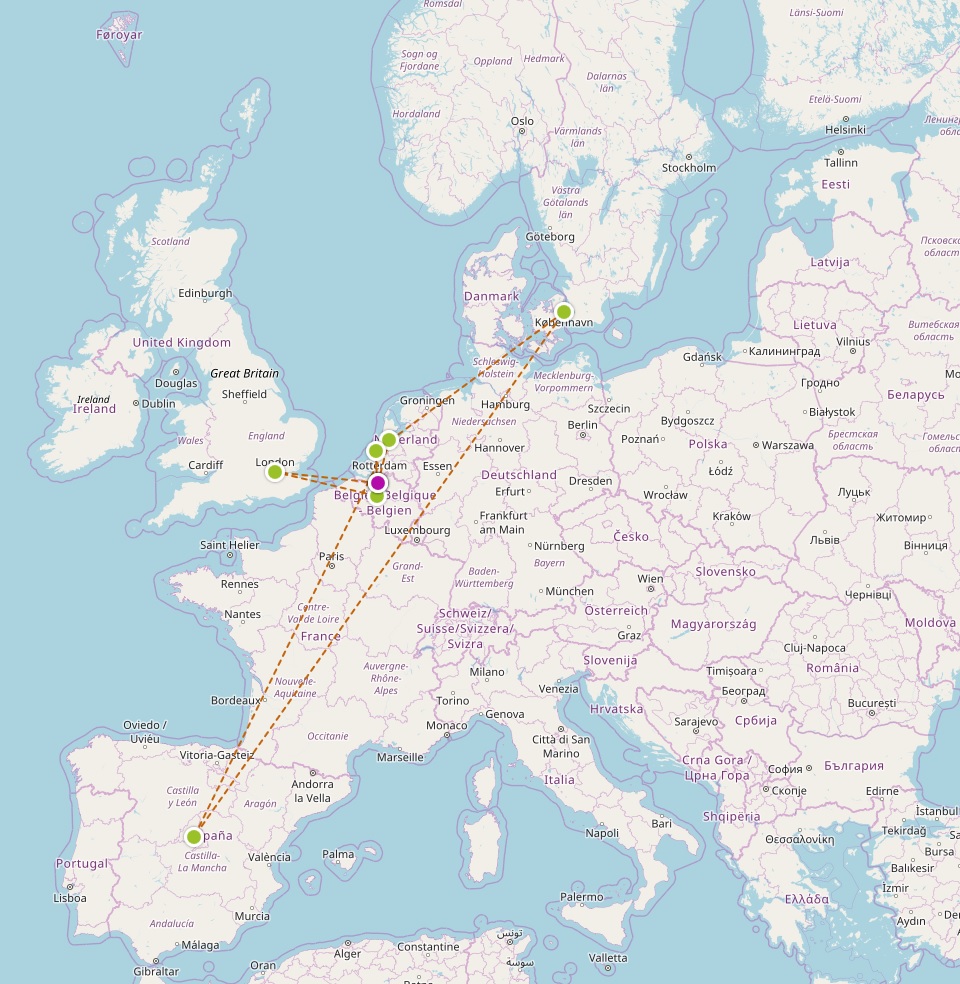

Theodore’s career as drawn on the map of Europe (source: RKD)

Lope had revolutionised Spanish theatre by the introduction of the comedia nueva, or new comedy, which did not adhere to any specific poetics but that of popularity. In his manifesto Arte Nuevo de Hacer Comedias en Este Tiempo (1609), Lope explicated the art – or rather lack of art – of the ‘new’ Spanish comedias, including the mixing of the tragic and the comic. Although he knew the established rules of poetry very well, he refused to follow them on the grounds that his audience cared nothing about them.

Corral de comedias in Almagro (Spain), preserved from the seventeenth century (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Rodenburgh got inspired and he would adapt the plots of four Spanish comedias – three by Lope de Vega, one by Gaspar de Aguilar (1561-1623). With his adaptations, Rodenburgh reaped many successes, seeing that the profits of Rodenburgh’s adaptations were comparable to the most performed play Gysbreght van Aemstel (1637) by the Prince of Poets Joost van den Vondel (1587-1679). Therefore, Rodenburgh deserves a lot more praise than he is generally given.

New Opportunities in Amsterdam

Much to his regret, Rodenburgh could not hold on to a diplomatic position in Madrid. He finally returned to Amsterdam and became the chairman of the rhetoricians’ chamber ‘The Eglantine’. Three of its foremost members had just broken away with the literary institution to establish the First Dutch Academy.

The building of the First Dutch Academy at the Keizersgracht in Amsterdam (source: Beeldbank Amsterdam)

The playwrights Samuel Coster, P.C. Hooft, and G.A. Bredero would fashion their plays according to the principles of the Leiden professors Justus Lipsius and Joseph Justus Scaliger: staid plots based on Senecan horror plays with a clear (neo)stoic undertone, meaning that reason was always preferred over emotions. The playwrights, therefore, disliked Rodenburgh’s Spanish plays for their excessive rendering of emotions in the characters. And so in the years that followed, Coster and Bredero fiercely attacked Rodenburgh’s literary output. Coster had, for instance, said in his introduction to his Isabella (1619) that he, who follows the ancients, understands that a play is good, when it represents one place, and when it plays out at one time, for he who does not abide by these rules, blunders greatly. (trans. of Coster, Isabella, *2r.)

In 1647 – three years after Rodenburgh’s death – Vondel wrote about Rodenburgh’s Hertoginne Casandra en Karel Baldeus (1617):

On Casandra’s Tragedy.

Rest in peace horny Duchess, smother your cursed fire;

The sweet lust still ill befits a tyrant;

How keeps Casandra nagging on to Karel,

While neither scheme nor trick pulls him away from Leonora.

(trans. of Vondel, De werken, II, 261)

Vondel disliked Duchess Casandra for her emotionality and the way she falls in love with the chamberlain of her husband. The play itself had, however, been a great success with place seven in the popularity charts of the Amsterdam Municipal Theatre. That popularity did not prevent Rodenburgh’s colleagues from repeating their distaste. While Vondel had been quite civil in his critique, Mattheus Gansneb Tengnagel wrote in 1652 that ‘all his twenty-six plays are not worth one play’.

Entrance Gate to the Amsterdam Municipal Theatre built by Jacob van Campen at the Keizersgracht (source: Wikimedia commons)

The Inner Agitations

Especially those feelings of love and lust allowed Rodenburgh’s plays and those of many of his followers in the 1640s-1660s to become box-office successes in the Amsterdam Municipal Theatre. In the Dutch adaptations of the comedias, characters keep expressing their most innate feelings as woelingen [inner agitations] that represent inner conflict leading to an emotional climax. In Casandra en Karel, Casandra bursts out in song, saying about her situation:

Casandra:

That I bestow my love

Upon the duke’s chamberlain,

And cannot force my own hand,

That is, alas, my sad infliction.

Speak up, you mournful eyes,

So that he [Karel] will understand you

Through your expression, without words,

And commiserates with you. […]

Ah, shall I in order to silence

The agitation [woelingh] of my soul [zin],

Tell him that I love him?

No one will believe me.

(trans. of Rodenburgh, Casandra en Karel, vss. 66-73, 86-89

by Van Marion & Vergeer 2016)

An example of ‘Weeping and Melancholia’ in Franciscus Lang (1727), Dissertatio de actione scenica (source: Bayerische StaatsBibliothek)

This emotionality was both the play’s success and downfall. The last performance of Casandra en Karel was in 1678. Thereafter, the Amsterdam society of poets Nil Volentibus Arduum took over and did away with all plays that did not conform to their classicist ideals, and so Rodenburgh disappeared from the stage. The frontman of NVA, Andries Pels, wrote in 1681 about the Spanish plays that:

Their disposition is wild in place, and time; but all the world praises its contents, scholars and laymen alike. (Pels, Gebruik én misbruik des tooneels, vss. 1066-1067)

Despite its popularity, Casandra en Karel as well as Rodenburgh’s other plays were thought of as lacking poetic quality.

Rodenburgh’s Demise

In the eighteenth century, Rodenburgh was almost forgotten, but the nineteenth century was especially unkind to the playwright. For instance, in 1875, J. van Vloten called Rodenburgh ‘a knight of a sad posture’. This was after Jacob van Lennep had already discussed Rodenburgh’s skill at writing verses. In his De Werken of Vondel (1855-1869), he had said that Rodenburgh’s plays may have enjoyed a flood of visitors, but that reading any of his plays was a hardship, since the poet wrote the most dreadful verses that falter and are interspersed with what Van Lennep called ‘bastard words’.

Although Rodenburgh had written more exciting plays, Vondel was preferred by Nationalists. Vondel and not Rodenburgh was included in the Dutch Canon along with Hooft and Bredero. It is an interesting contradiction that the audiences preferred the rendering of emotions in Rodenburgh’s plays, but that the literary elite liked Vondel’s staid plots better. That contradiction must, however, be the subject of another blog post.

Further Reading

This article discusses Rodenburgh’s three Lope-adaptations and how Rodenburgh managed to introduce the comedia nueva in the Dutch Republic. The article is part of a larger research agenda on the creative industry of Dutch theatre in the seventeenth century.

Rodenburgh, Th., Casandra Hertoginne van Borgonie, en Karel Baldeus. Amsterdam 1617.

Recently, a great edition of this play was published on Census Nederlands Toneel (Ceneton).

Great overview articles and studies on Dutch Renaissance theatre and Rodenburgh’s role (or lack thereof) in the construction of a national literature are:

Abrahamse, W., Het toneel van Theodore Rodenburgh. Amsterdam 1997.

Smits-Veldt, M.B., Het Nederlandse renaissance-toneel. Utrecht 1991.

Worp, J.A., ‘Dirk Rodenburg’, Oud Holland - Quarterly for Dutch Art History, 13.1 (1895): 65-90; 143-173; 209-235.

0 Comments