The Privacy of the Bedchamber: The Stages of Love in Dirc Potter’s Der minnen loep

The late medieval author Dirc Potter gave his readers dating advice, specifying not only what to do at each stage of love but also where to do it. Not surprisingly, the last stage of love takes place in the privacy of the bedroom.

Fig. 1 Binding of Universiteitsbilbiotheek Leiden, LTK 205, one of the two surviving manuscripts of Der minnen loep. reproduced with kind permission of Leiden University Libaries.

Practical advice on love can nowadays be found in magazines and self-help books, but in medieval times one could consult an ars amandi, such as Dirc Potter’s (c. 1370-1428) Der minnen loep (The Course of Love). Potter lists four stages of love (gradus amoris), a common trope that originated in Latin literature. The stages were not a fixed set, but usually consisted of five steps: seeing, speaking, kissing, touching and the deed (visus, alloquium, osculum, tactus and factum). However, many variants with a smaller or larger number of stages can be found.[1]

At Potter’s first stage, the (male) lover likes to see his beloved and communicates his love by looking at her, by speaking to her in a friendly manner and by touching her hand.[2] This first approach takes place in the public space: on the street or in the field (opter straten of op dat velt). Also, the man walks passed the house of his beloved to catch a glimpse of her. The second stage is set in the garden (inden gairde). The lovers greet each other friendly, take each other by the hand, speak sweet words, give each other flowers and eventually kiss goodbye. At the third stages they go inside and up into a room, where after falling down on the bed (up een koetskijn) they kiss and embrace, exchanging sweet words again, and the man is allowed to touch the woman’s neck, cheeks and breasts. The fourth and final stage, coitus, is only preserved for marriage and takes place on the bed (opten bedde).

Potter is not very traditional in his description of the stages of love. He does not primarily structure them around sensual acts, but by the locations in which the acts take place. The lovers go from the public outside world to the intimate bedchamber. The stages seem to have some fluidity: the bed occurs in the third and fourth step, and several acts and gestures, such as kissing, are part of more than one stage.

Although Potter talks about worldly love, the connection between physical acts of love and (indoor and outdoor) locations has some close parallels in the tradition of divine love inspired by the Old Testament Song of Songs. Verse 1:16 of the Song in particular lends itself to such associations: “Behold you are fair, my Beloved, and comely! Our little bed is flowery.” William of St.-Thierry, who wrote a commentary on the Song, interpreted this bed as the place where the kiss takes place: “Upon this bed are exchanged that kiss and that embrace by which the Bride begins to know as she herself is known.”[3] The other locations mentioned by Potter, the field, the garden and the bedchamber, occur in the Song as well. Bernard of Clairvaux, in his sermons on the Song, described a movement similar to Potter's, from the outside world to the inner bedchamber:

His eyes will see the king in his beauty going before him into the beautiful places of the desert, to the flowering roses and the lilies of the valley, to gardens where delights abound and streams run from the fountains, where storerooms are filled with delightful things and the odours of perfume, till last of all he makes his way to the privacy of the bedchamber.[4]

Fig. 2 Binding of Universiteitsbilbiotheek Leiden, LTK 205. reproduced with kind permission of Leiden University Libaries.

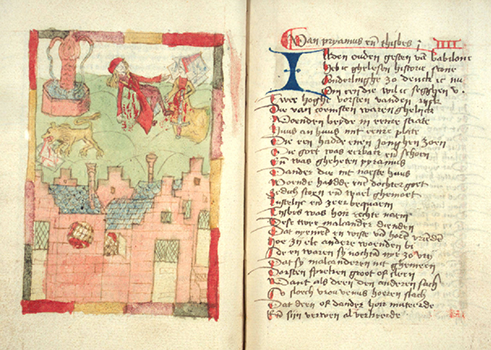

One of the two surviving manuscripts of Der minnen loep is kept in Leiden: Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, LTK 205. It was made in 1486 in Holland and contains many illustrations. The images often include both an exterior and interior view, which can, in some instances, be connected to specific stages of love. An example is the famous Ovidian story of Pyramus and Thisbe. In the version of the story told by Potter, they were lover who only had seen each other through a small latticed window. When they arranged to meet each other at a well outside of town tragedy struck: Thisbe, who arrived first, encountered a lioness that came to drink at the well. She fled, but left her cloak, which the lioness tore apart with her blooded teeth. After finding the ripped and blooded cloak, Pyramus assumed that his beloved had died and stabbed himself with his sword. When Thisbe came back and found the dead body, she followed him in his death.

Fig. 3 Universiteitsbilbiotheek Leiden, LTK 205, ff. 102v-103r: The deaths of Pyramus and Thisbe. reproduced with kind permission of Leiden University Libaries.

Potter uses this story as an example of love that never came past the first stage. He warns lovers not to rush but patiently await the second stage. The illustration shows the two dead lovers in a hilly field. In the front we can see the houses of the town, with the latticed windows.

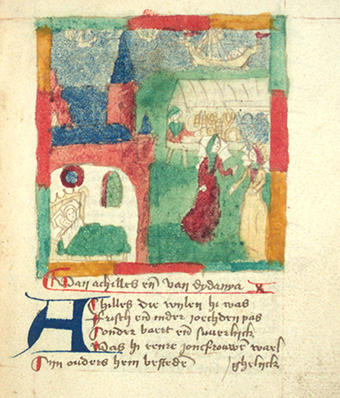

An example of the fourth step is the story of Achilles and Deidamia. Achilles, disguised as a woman, sleeps in Deidamia’s bed and goes, against her will, to the fourth stage. Deidamia is angry with him and only when Achilles leaves she realizes she loves him. The moral of this story about love is of course horrible according to our standards and not something we would find in modern self-help books about love: although violence is not permitted, sometimes a man has to ‘help’ a woman to overcome fear by using a list.

Fig. 4 Universiteitsbilbiotheek Leiden, LTK 205, f. 126r: Achilles and Deidamia in bed. reproduced with kind permission of Leiden University Libaries.

In the illustration we see the two ‘lovers’ in bed. They are closed off from the public life that is going on outside: some things belong to the privacy of the bedchamber.

[1] Matthew of Vendôme, for example, listed six, and Andreas Capellanus four. See Lionel J. Friedman, “Gradus amoris.” Romance Philology 19 (1965/66): 172.

[2] Dirc Potter, Der minnen loep, ed. Pieter Leendertz (Leiden: Du Mortier, 1846), 180.

[3] “Ibi etenim comparat se sibi ille amplexus et illud osculum, quo cognoscere incipit sponsa, sicut et cognita est.” William of St.-Thierry, Expositio super Cantica Canticorum XX.91, in Guillelmi a Sancto Theodorico Opera omnia. Pars II, ed. Paul Verdeijen, Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Mediaevalis 87 (Turnhout: Brepols 1997), 70; translation: William of St.-Thierry, Exposition on the Song of Songs, transl. Columba Hart (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1970), 78.

[4] “Regem in decore suo videbunt oculi eius, praeuntem se ad speciosa deserti, ad flores rosarum et lilia convallium, ad amoena hortorum et irrigua fontium, ad delicias cellarorium et odoramenta aromatum, postremo ad ipsa secreta cubiculi.” Bernard of Clairvaux Sermones super Cantica Canticorum 32.IV.9, in Sancti Bernardi opera I, ed. Jean Leclercq (Rome: Editiones Cistercienses, 1957), 232; translation: Bernard of Clairvaux, On the Song of Songs II, transl. Kilian Walsh (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1983), 142.

© Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments