To ‘Be Happy!’ - or Not to Be

In her research, Esther Op de Beek works on happiness in contemporary literature. In the context of our 'Arts in Society' theme, she challenges the common idea that we should always strive for happiness through a range of literary examples.

A few weeks ago, on March 20th, the International Day of Happiness was celebrated, a day to promote ‘a more inclusive, equitable and balanced approach to economic growth that promotes the happiness and well-being of all peoples’. The ambition to create equality is not new, since as early as 1776 ‘equal chance of happiness’ was included as a fundamental human right in the Declaration of Independence. The link between happiness and economic growth, however, is of a more recent date. This altered concept of happiness has been in spotlight in various scientific disciplines in what is called the Happiness Turn, often in conjunction with, or in response to, the Happiness Industry. Think of the piles of self-help books with titles such as How to Be Happy or Eight Steps to Happiness, magazines as Flow and Happinez, promoting mindfulness and yoga, or what Slavoj Zizek cynically called Western Buddhism. For the Happiness Industry, happiness is a positive emotion or positive way of thinking that can be achieved by working on something or buying something. This view receives thorough criticism from ethicists, psychologists and cultural scientists.

Every year, the UN ranks countries in terms of their population’s self-reported well-being, as well as perceptions of corruption, generosity and freedom in the World Happiness Report, which is presented on March 20th. This year, Finland tops the list in the ranking of 156 countries, followed by the other Scandinavian countries. The Netherlands has overtaken Switzerland to move into fifth place and Southern Sudan is considered the most unhappy country.

In The Promise of Happiness, Sara Ahmed, a scholar working at the intersection of feminist, queer and race studies, criticizes the assumption underlying the report, that happiness is a measurable indicator for growth and advancement. She argues that much of the new science of happiness is premised on a simplistic model that presumes the transparency of self-feeling (that we can say and know how we feel), as well as the unmotivated and uncomplicated nature of self-reporting. In short, if something is good, we feel good and to say you are happy, is to be happy. When belonging to a majority group, having a high position on the social ladder, a family, many friends, being physically and mentally healthy, one is assumed to have reached a state of pure happiness:

“It is not just that people are being asked to evaluate their life situations but that they are being asked to evaluate their life situations through categories that are value laden. Measurements could be measuring the relative desire to be proximate to happiness, or even the relative desire to report on one’s life well (to oneself or others), rather than simply how people feel about their life as such.” (Ahmed 6)

Moreover, Ahmed argues that in our modern society, happiness has detached itself from the meaning ‘to happen’ – thus from luck, faith or contingency – and has become a duty. The French philosopher Pascal Bruckner draws the same conclusion in his book Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy. Referring to the marketization of happiness, he states:

“‘Be Happy!’. This apparently amiable injunction, is there another, more paradoxical, more terrible? The commandment is all the more difficult to elude because it corresponds to no object. How can we know whether we are happy? Who sets the norm? Why do we have to be happy, why does this recommendation take the form of an imperative? And what shall we reply to those who pathetically confess: ‘I can’t’?” (Bruckner 2)

There is a compelling tendency to share motivational and inspirational happiness quotes on social media: recommendations that often take this form of an imperative, so I’ve argued here.

Although there is a vast body of studies about happiness by economists, historians and philosophers, within the field of literary studies, happiness has received relatively little systematic attention. It is not literary unless it is dark – ‘le bonheur se raconte mal’, as Gustave Flaubert famously stated. Happiness is considered superficial, cheap or uninteresting, although there’s hardly any work of fiction that doesn’t addresses the question of happiness, one way or another. Furthermore, our thinking about happiness and suffering is conditioned by stories and by a mostly unconscious set of narrative options. Narrative paradigms – such as: life as a trial, or life as a tragedy – influence how we think about personal or collective agency or fate.

In my research, I analyse representations of happiness in contemporary literature. Authors of 21st century fiction seem to broach the question of the nature of happiness in a very explicit way. In their novels, the pressure to ‘Be happy!’ – to be heroic, the be unique, to be authentic, to be a good citizen, to be a happy family, to be happily in love, to be anything but mediocre or meaningless – is omnipresent, but this pressure is portrayed in very different ways representing very different attitudes towards the imperative in juxtaposition. Literary texts have the possibility to show the discrepancy between experienced feelings and thoughts about happiness on the one side, and shared emotions or actions on the other. The exact idea that people might not report a measurable happiness to each other or themselves, but instead respond to the happiness imperative – constantly comparing themselves, or their social media profiles, reflection – seems to be a dominant principle in the narrative structures and imagery in the novels.

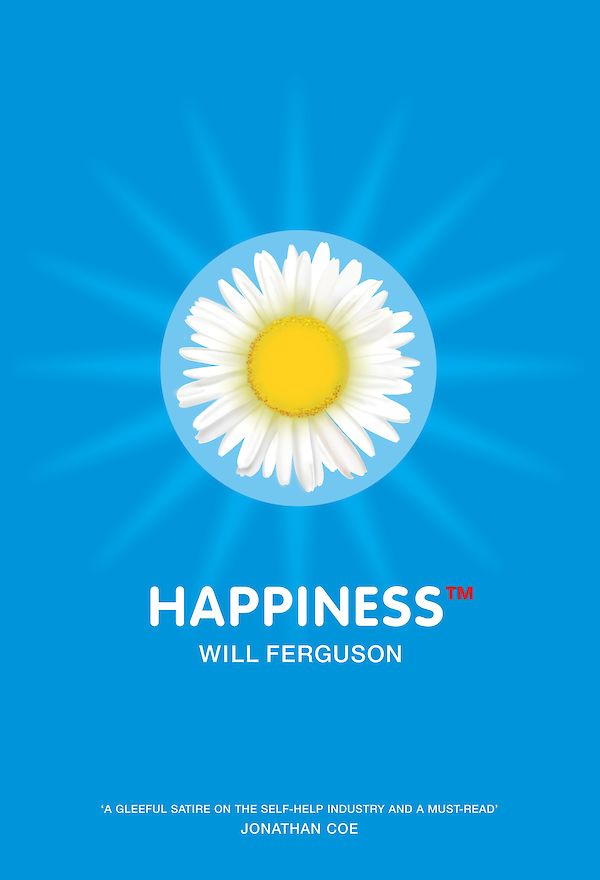

Of course there are novels that go along with the idea that happiness is achievable and should be strived for. The novels of Griet Op de Beeck, for instance, seem to provide coping strategies to deal with the pressure: you don’t have to be a victim anymore, you too can be happy – a message that speaks to large audiences. But there are also authors that urge us to take a step back and question the imposed duty. What happens if characters refuse it? Read: Wilhem Genazino, Das Glück in glücksfernen Zeiten (2009) or Jannah Loontjens, Veel geluk (1999). What if they think happiness is a Western merit? Mentioning Arnon Grunberg here will give you an indication of the answer, read: Het aapje dat geluk pakt (2005). What if a self-help book actually ‘works’ and everybody becomes completely satisfied? Read: Will Ferguson, Happiness TM (2002). And what does happiness mean in a world without class, gender and very limited identity options, inhabited by animals that tend to be philosophical? Read: Toon Tellegen, Het geluk van de sprinkhaan (2011).

I am convinced that, by studying these literary experiments – their narrative structures, imagery, affects and emotions – as portraits of our late modern human condition, literary studies can contribute to analyzing and contextualizing the collective obsession with happiness, and the ways in which happiness is quantified, marketed and depoliticized. Here you can find a more detailed analysis by means of an example.

To conclude with a bit of literature: in Dutch literature, happiness sometimes gets the shape of nostalgia for the neat, but somewhat narrow-minded, domesticity in the forties and fifties. In this beautiful poem by Mark Boog for example, happiness is a physical object, placed in a display case, only to be looked at, carefully, together.

|

GELUK Het geluk is overkomelijk. Men plaatst het |

HAPPINESS Happiness is surmountable. One places it |

© 2005, Mark Boog

From: De encyclopedie van de grote woorden

Publisher: Cossee, Amsterdam, 2005

© Translation: 2006, Willem Groenewegen

Literature / further reading

S. Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness, 2010.

P. Bruckner, Perpetual Euphoria: On the Duty to Be Happy. trans. Steven Rendall, 2011.

A. Corkhill, Spaces for Happiness in the Twentieth-Century German Novel, 2012.

J. Pawelski & D. Moores (red.), The Eudaimonic Turn. Well-Being in Literary Studies, 2013.

V. Soni, Mourning Happiness. Narrative and the Politics of Modernity, 2010

© Esther Op de Beek and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to the author and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments