Trump and Philip of Thessalonica Undermining Authorial Control

What do Donald Trump and Philip of Thessalonica have in common? In this blog, Oriol Febrer argues how both of them challenge the power of other artists to determine the meaning of their creations. They purposely change the meaning of previous texts by shaping new contexts.

The 2024 US presidential elections are just around the corner. Among other things, this means that Europeans too are likely being bombarded with news on the ongoing campaign through their screens, both by publicly and privately owned media. In the cultural war in which an increasingly polarised US society seems to be wrecked in recent decades, music played at Donald Trump’s political rallies of the 2016, 2020 and 2024 election campaigns has been object of polemics too. Throughout the years, several artists have protested Trump’s use of their music and videoclips and, in some cases, they have even taken legal action against it. The last ones to do so, during the present campaign, include ABBA, Beyoncé, and Celine Dion.

Leaving aside the legal aspects of the matter, the artists’ concern for the use of their songs in unwished contexts attests to the fragility of authorial control on the meaning of fixed texts or lyrics. A similar anxiety was already present in Plato’s dialogue Phaedrus, written in the first half of the fourth century BC (275D-E, translation by David Horan):

The artists’ concern also bears witness to the power of relocating a piece of art and its potential effects on both the text’s meaning and artist’s public representation. A good example of this could be the use of Bruce Springsteen’s celebrated hit ‘Born in the U.S.A.’ during several political rallies of Trump’s presidential campaign in 2016. In fact, Republican Ronald Reagan had already planned to adopt it for his re-election campaign of 1984, in vain. During Trump’s campaign, focused on opposing illegal immigration, Springsteen’s song, critical with US politics and society, was presumably turned into a rapturous celebration of US identity based on autochthony ―ironically enough, given the allochthonous origins of the majority of present-day US society. Regarding the power exerted on Springsteen’s public image, his long-lasting support for the Democrats was threatened by the appropriation of his song by Trump’s discourse.

Mutatis mutandis, editors of ancient collections of Greek epigrams exerted a similar type of power on the texts which they collected and rearranged. Epigrams, short poems originally inscribed on gravestones, statue bases, and other objects like cups, made their way into books in the late Classical and early Hellenistic periods, in the fourth century BC (e.g. Garulli 2019). They became refined literary artifacts in which epigrammatists strove to surpass each other in inventiveness, erudition and wit by composing on the same themes or by varying already extant epigrams. In this literary genre, then, the position of an epigram in relation to other epigrams in the columns of a papyrus roll was a key element for its interpretation and for the reader’s enjoyment.

As shown chiefly through papyrological fragments, anthologies of epigrams circulated from the Hellenistic to the early Byzantine period (Maltomini 2019). Although we have not preserved any anthology in its entirety, traces of them and plausible partial reconstructions proposed by scholars point out that the editors of these epigrammatic collections played a major role in reshaping the meaning of an individual epigram by choosing its surrounding poems. Some editors were even epigrammatists themselves and added their own compositions, carefully devised to appropriate the collected epigrams.

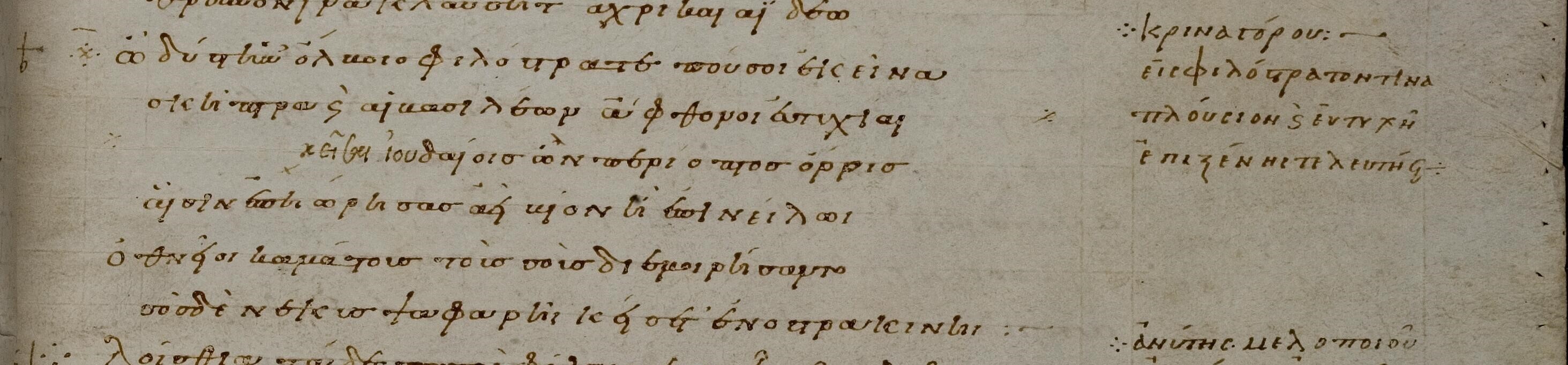

Let us take, for instance, an epigram of Crinagoras of Mytilene (ca. 70 BC – ca. 15 AD), who, besides writing epigrams, was a member of the local elite of his island, Lesbos, well-connected with the Roman imperial court. In the following epigram, he laments the fall from grace of a certain Philostratus ―identified with a philosopher active at Cleopatra’s court in Alexandria―, now exiled to Ostracina, in the Egyptian desert (Anthologia Palatina VII.645, translation by Ypsilanti 2018):

We know nothing of the original context of this epigram. In itself, however, it seems to be alluding to a historical event: Philostratus’ exile. Most modern scholars are inclined to perceive in these verses a compassionate tone for Philostratus’ fate, and perhaps even a slight hint of criticism against the authorities who ordained his exile and seized his assets ―they are called, somewhat disdainfully, “strangers” (Ypsilanti 2018).

Personally, I am not so sure about that, mainly because of a wordplay which adds a layer of humour and seems to distance the reader from Philostratus’ suffering: the name of the town Ostracina (Ὀστρακίνη) transparently recalls the óstraka (ὄστρακα), the potsherds used in classical Athens to vote in ostracism processes, in which a citizen deemed a danger for Athenian democratic institutions could be forced into temporary exile (Węcowski 2022). Moreover, the sonority of Philo-stratus’ name (‘army-lover’), mentioned in the first line, would anticipate the pun by being just one letter away (*Phil-ostracus) from meaning ‘óstraka-lover’: nothing more natural than an ‘exile-lover’ heading towards ‘Exile City’!

Regardless of the original meaning of Crinagoras’ poem, its inclusion at the end of Philip’s Garland, a first-century anthology of epigrams, entails a semantic shift. Philip of Thessalonica, the remains of whose anthology are scattered in later, Byzantine anthologies, arranged his materials primarily following an alphabetical sequence. Inside and across alphabetical sections, however, he seems to have organised thematic units, with series of epigrams in dialogue with one another (Höschele 2019). To one of these series seems to have belonged Crinagoras’ epigram.

The majority of epigrams in the omega section, the last section of the Garland, either suggests the idea of completeness and closure or threatens whoever may damage the book or its content ―similar curses have been found at the end of papyrus rolls (Höschele 2018). In Anthologia Planudea 93, Philip himself, for example, recounts the accomplishment of Heracles’ multifarious labours in an unmarked first person, which can also be interpreted as Philip’s persona commenting on his varied anthology coming to an end. Poems ironically threatening readers from “messing” with his epigrams include Anthologia Planudea 241 and 240, in which the god Priapus menaces to rape whoever steals the ripe figs under his protection, or Anthologia Palatina VII.405, in which the tomb of Hipponax, a very caustic writer of iambic poetry, recommends the passer-by to run away, lest he wakes up Hipponax and his venomous verses.

In this new context, Crinagoras cannot prevent his epigram from suggesting an idea of completion ―Philostratus’ happy life / the pleasant reading of the anthology comes to an end, a kind of exile― or a slight threat, since, one would imagine, Philostratus’ exile would have been motivated by his own deeds, comparable to the ill-intended reader whom Philip wishes to keep away from his Garland.

To come back to contemporary US politics, it is not difficult to grasp why musicians such as ABBA or the Foo Fighters zealously wish to prevent Trump’s or Trump’s campaign directors’ use of their music. They want to salvage their authorial control on their public image and the meaning of their songs, which, as happened with Crinagoras’ epigram, can be modified by changing their context. They may succeed provisionally, but time will unstoppably keep eroding and altering the original meaning of their creations, just like water always ends up leaking in through the best protected roof.

© Oriol Febrer i Vilaseca and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2024. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Oriol Febrer i Vilaseca and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Further reading

Garulli, V. 2019. ‘The Development of Epigram into a Literary genre’, in C. Henriksén (ed.), A Companion to Ancient Epigram, Hoboken, 267-286.

Gow, A.S.F., Page, D.L. 1968. The Greek Anthology: The Garland of Philip and Some Contemporary Epigrams. Cambridge.

Höschele, R. 2018. ‘Poet’s Corners in Greek Epigram Collections’, in N. Goldschmidt, B. Graziosi (eds.), Tombs of the Poets: Between Text and Material Culture, Oxford, 197-215.

Höschele, R. 2019. ‘A Garland of Freshly Grown Flowers: The Poetics of Editing in Philip’s Stephanos, in M. Kanellou et alii (eds.), Greek Epigram from the Hellenistic to the Early Byzantine Era, 51-65.

Maltomini, F. 2019. ‘Greek Anthologies from the Hellenistic Age to the Byzantine Era: A Survey’, in C. Henriksén (ed.), A Companion to Ancient Epigram, Hoboken, 211-227.

Węcowski, M. 2022. Athenian Ostracism and its Original Purpose: A Prisoner’s Dilemma. Oxford.

Ypsilanti, M. 2018. The Epigrams of Crinagoras of Mytilene: Introduction, Text, Commentary. Oxford.

0 Comments