“Whatever Will Be Will Be” in Spanish Plays

When you are fluent in a language, you can still make mistakes. This is what happened to the Dutch playwright Theodore Rodenburgh when he adopted his life’s motto “Chi sara sara”.

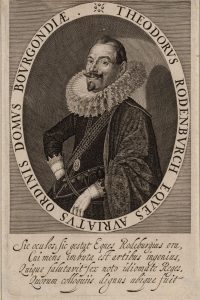

Theodore Rodenburgh (1574-1644) was a productive playwright who adapted four plays from Spanish, several plays from English, and a few plays from Italian. He, furthermore, adopted the motto “Chi sara sara” around 1617 to express his life’s philosophy. He explicitly added the motto to the forewords of his three adaptations from Spanish. Lope de Vega’s El perseguido (1603), El molino (1604), and La escolástica celosa became Hertoginne Casandra en Karel Baldeus (1617), Hertoginne Celia en Grave Prospero (1617), and Jaloersche studenten (1617) respectively. All three forewords by Rodenburgh are ended by the same motto written as “Chi sara sara”. Instead of signing his own name to the adaptations, Rodenburgh added this motto to indicate that he was the author. Everyone in the literary circles of Amsterdam knew that he used this phrase specifically. And so, it was a kind of joke.

As a productive adaptor of Spanish plays and having lived in Madrid for several years, it would not be strange that Rodenburgh would use a motto from the Spanish language to refer to his own work. With this motto, he could also express that the plays that he wrote subscribed to a certain sustained morality.

There is, however, a problem with the motto “Chi sara sara” (or as it is written more often: “Che sara sara”). It seems to be Italian and not Spanish. In Spanish, we would expect the phrase to read “Que sera sera”, such as in the song of the same title in the 1956 movie The Man Who Knew Too Much and popularized by Doris Day afterwards. This is also how most people know the phrase today. But what did Rodenburgh do 350 years earlier? Did he mistakenly select the Italian form? That would be strange for someone who was fluent in at least four languages, including Italian and Spanish. And it gets even stranger.

Doris Day, Que Sera Sera (1956)If one takes a closer look at the phrase, it seems that Rodenburgh’s motto “Chi sara sara” and its Spanish variant “Que sera sera” are neither Italian nor Spanish after all. Rodenburgh did not only select a phrase from the wrong language, he made a grammatical mistake as well.

What is actually the matter? The slogan, both in its Spanish spelling—que sera sera—and in the form used by Rodenburgh—chi sara sara—is grammatically incorrect. In 2013, Lee Hartman has demonstrated how most speakers of Germanic languages will understand the Spanish “que” in the motto “que sera sera” as a free relative pronoun, paraphrased by “that which” or “the thing that”. This is, in fact, impossible in Romance languages. In French, Italian, and Spanish, the interrogative function of “what” is a single word (Spanish qué, Italian che, and French que). Hartman writes that “the free relative is a two-word expression—Spanish lo que; Italian ciò che, quello che, or quel che, interchangeably; and French ce qui for the subject of a clause, or ce que for the direct object”.

Thus, if Rodenburgh had been observant he should have written “Quel che sarà sarà” if choosing the Italian form or “Lo que será será” if he preferred the Spanish spelling. Instead, he used a strange form in between. Does this mean that Gerbrand Adriaensz Bredero and Samuel Coster were right after all, when they said that Rodenburgh blundered greatly with his verses?

I think not. It seems that the history behind the phrase “que sera sera” and “che sara sara” is more complex and can actually be retraced to Elizabethan England. In fact, Hartman found that the earliest citation of the motto appears in Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (written between 1589–1592, published in 1604) with the Italian spelling “Che sera sera” (Doctor Faustus 1604, I.i.). It seems that the Italian spelling is even more frequent until the 1950s, although both the Spanish and Italian spellings are evident, serving both heraldic and expressive functions. The first purely expressive use of the motto appears, however, (with the Spanish spelling) soon after its citation in Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus. Hartman writes that we have to look at Edward Sharpham’s play Cupid’s Whirligig, where the character Nucome says “Well, since tis thus, hence foorth ile loue thee euer, for que sera, sera, gainst what plots so euer” (Sharpham 1607, n.p.).

So Rodenburgh had the opportunity to adopt the motto from at least one of these two sources. Though, he did not choose the Spanish spelling in Cupid’s Whirligig but he preferred the Italian one in Doctor Faustus instead. Why did he, however, look at the English and not to the Spanish literature to get inspiration for a new motto? Wouter Abrahamse has discussed that Rodenburgh was as a polyglot interested in all kinds of literary traditions from around Europe, including the Spanish, English, and Italian literatures. Rodenburgh must have come across the phrase in one of the English sources and must have thought that it would serve him well as his life’s motto.

Then, there is still one question left to answer. Why did Rodenburgh choose the Italian and not the Spanish spelling? Although we can never be sure as to what moved Rodenburgh’s decision, it is possible to offer one suggestion. In the early seventeenth century, Italian literature from the Renaissance was more fashionable with literary examples, such as Dante Alighieri, Francesco Petrarca, and Matteo Bandello. Everyone who could afford it went on Grand Tour to Italy and marvelled at the Renaissance buildings in Tuscany and at the ancient wonders in Rome. As such, choosing the Italian spelling attests to a form of self-fashioning: pretend to be as Italian as possible, because this will get you places.

Moreover, Spain was also officially still the arch-enemy of the newly formed Dutch Republic. Showing that you were sympathetic to forms of Spanish culture could be dangerous to your literary or otherwise professional career. Thus, Rodenburgh also carefully concealed any reference to the Spanish origins of the three Lope adaptations. The three plays rather seemed adaptations directly from Bandello’s Novelle, than recasts from the Spanish comedias. It was Rodenburgh’s literary strategy to hide his sympathy for Spanish culture but to use this culture at the same time to score with the general public.

And Doris Day? She scored with the Spanish spelling of the same phrase. In 350 years’ time, Spanish has become cooler than Italian. And so everyone says “que sera sera”, although it is still actually incorrect. But who cares? It is a nice catchphrase.

Further reading

Hartman, Lee, ‘“Que sera sera”: The English Roots of a Pseudo-Spanish Proverb’, Proverbium, 30 (2013): 51-104.

Marlowe, Christopher, Doctor Faustus. London: 1604.

Sharpham, Edward (1607). Cupid’s Whirligig. London: E. Allde. Cambridge 1996.

Abrahamse, Wouter, Het toneel van Theodore Rodenburgh. Amsterdam 1997.

© Tim Vergeer and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Tim Vergeer and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments