Where have all the women gone? Challenging structural patriarchy and rethinking feminist art history

Where have all the women gone? It can be difficult, sometimes, to find evidence of female participation in the arts and culture of the early modern period. Catherine Powell explores how we can locate women and their participation by asking different questions.

Early on in my research regarding the history of art of the seventeenth-century in the Dutch Republic, I began grappling with an apparent contradiction: if the women of the young Republic were freer, tended to have more economic power, and were better educated than their counterparts elsewhere in Europe, why was there so little discussion regarding their roles as artists and patrons? Surely, seventeenth-century Dutch women were more than milkmaids and fishwives?

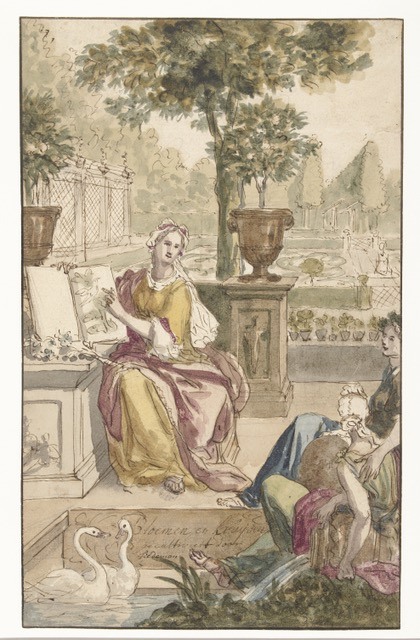

The good news is that many early modern Dutch women were indeed active and influential in the cultural and artistic spheres, and even contributed to the development of natural sciences. The subject of my PhD research, Agnes Block (1629-1704), was one of these women: she bought and developed a country estate, commissioned paintings and watercolours, and assembled a collection of naturalia and exotica. With her knowledge of botany, she earned the respect of learned men, who mentioned her in their scientific treatises.

Unfortunately, as I have discovered, finding early modern women is not an easy task. Why is it so difficult to write women into art history? One answer lies in the enduring and driving—and frequently hidden—narrative of the “lone male genius artist” coursing through sources and methodologies. Instinctively, we look for masterpieces that hang in museums, for artists that produced many panel paintings, or those who had large workshops. More often than not, we discover that the artists who fit these categories were men.

To truly write women into art history, one must therefore begin by recognizing the structures built upon the myth and by responding with adapted methodological tools.

There are multiple examples of early modern women who played a significant role in art history. In the early 1680s, the Amsterdammer Adriana Spilberg followed her painter father to the court of the Elector Palatine, in Düsseldorf. There, in addition to creating pastels, she painted the frescoed ceilings of the palace, the only known Dutch female artist to work in that medium.[i] Johanna Koerten’s paper cutting art was so highly prized that when she died in 1715 in Amsterdam, tributes by artists, poets, and other luminaries continued to accumulate in her friendship album (album amicorum). In the early eighteenth century, Dorothea Maria Graff moved from Amsterdam to St. Petersburg, where she participated in the foundation of the Tsar’s Chambers of Art and Curiosities (known today as the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography) and became a drawing instructor.[ii]

But few paper cuttings survive, when they are recognized as art at all; drawings have often been ignored by art historians in the past, and the women did not have apprentices. And none of these women are the subject of monographs or book-length studies. They seldom appear in online databases of artists. When they do, they are daughters, sisters, and wives first and foremost. An entry for Spilberg is representative. In its entirety, it consists of the following:

Spilberg, Adriana or Spielberg

Dutch, 17th century, female.

Born c. 1657, in Amsterdam.

Painter, pastellist.

Adriana Spilberg was the daughter and pupil of Johannes Spilberg. In 1684 she married Wilhelm Breekvelt in Düsseldorf and in 1697, Eglon van der Neer.

That three women of such talent be reduced to this implausibly thin summary is not the product of malevolent intention. Research depends heavily on the primary sources that are found in the archives. This is the problem: archives are not neutral. The very act of collecting and organizing art, papers, and other documents involves a determination: of who and what is important, of who and what should be remembered and preserved for future generations and, critically, of how best to organize this information. For centuries, this decision-making process has privileged institutional status. This has resulted in the exclusion women (together with religious and racial minorities and countless “others”), prioritizing instead successful and/or leading men.

Thus Johanna Koerten, who spent her entire life in Amsterdam, is invisible in the index of that city’s archives. One may, however, find relevant information about her by looking into the collected documents of her husband, Adriaan Blok. Devotion to the patriarchal family model has been carried from the record keeping of the early modern period through to the contemporary digitization of the archives.

It is unrealistic to expect that hundreds of thousands of kilometers of archives will be reorganized. A key to challenging the structural bias of the archives, therefore, is to interrogate primary sources and approach our research in ways that allow us to overcome this impediment. My approach has been to look for women, differently. Instead of looking for individuals, I have found that a productive way of finding information is to search for relationships, which can be potent tools in recovering the lives of early modern women.

Although archives often reveal little about women, what we do know is that, just as we do today, they maintained relationships: with husbands, fathers, collectors, and many others. From this perspective, social network analysis is inherently compatible with a public or institutional approach to art history. Looking for relationships – for contacts, trades, exchanges, and even mere physical presence, as opposed to searching for an individual woman, can tell us about the communities in which women participated; how they negotiated the limits imposed upon them by their gender; and how they cultivated influence and commissions, amongst other things.

So instead of asking “where are Adriana Spilberg’s letters?”, a question unlikely to yield an answer, why not ask “whom in the entourage of the Elector Palatine might have met or been writing about Adriana Spilberg?” By reframing our inquiries, we can reconstruct communities of women and develop persuasive theories about how they used relationships and extended their influence with one another, but also within the broader society in which they existed.

It is undeniable that attempting to weave a web of relationships, rather than isolating a single node in a network, has required me to spend a long time in the archives. But there are great rewards in doing so, not the least of which is finally giving Agnes Block her place in art history. Incidentally: Johanna Koerten and Dorothea Maria Graff almost certainly knew one another: Graff’s mother, Maria Sibylla Merian, wrote in Koerten’s friendship album (album amicorum). Russia’s Peter the Great was one of their patrons.

Notes

I wish to thank Elizabeth Harding and Jaya Remond for their insights into this topic and for their comments on the text. I am also grateful for the comments Jeffrey Chipps Smith and Robert Brooks Warren have made on an earlier draft of this essay.

[i] Julia Kathleen Dabbs, Life Stories of Women Artists, 1550-1800: An Anthology (Farnham, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009), 168. See also Margarita Russell, "The Women Painters in Houbraken's Groote Schouburgh", Woman's Art Journal 2, no. 1 (1981): 8.

[ii] Ella Reitsma and Sandrine A. Ulenberg, Maria Sibylla Merian and Daughters: Women of Art and Science (Zwolle: Waanders Uitgeverij, 2008), 236-237.

Further Reading

Blouin, Francis X., and William G. Rosenberg. Processing the past: contesting authority in history and the archives. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Dieteren, Fia, and Els Kloek, eds. Writing Women into History. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam History Seminars no. 17, 1990.

Head, Randolph C. “Documents, Archives, and Proof around 1700.” The Historical Journal 56, No. 4 (December 2013): 909-930.

Honig, Elizabeth Alice. "The Art of Being "Artistic": Dutch Women's Creative Practices in the 17th Century." Woman's Art Journal 22, no. 2 (2001): 31-39.

Jeu, Annelies de. ‘t Spoor der dichteressen: Netwerken en publicatiemogelijkheden van schrijvende vrouwen in de Republiek (1600-1750). Hilversum: Verloren, 2000.

Pal, Carol. Republic of Women: Rethinking the Republic of Letters in the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Marx, Axel. “Why Social Network Analysis might be relevant for art historians: a sociological perspective.” In Family Ties: Art Production and Kinship Patterns in the Early Modern Low Countries, edited by Koenraad Brosens, Leen Kelchtermans, and Katlijne van der Stighelen, 25-33. Turnhout: Brepols, 2012.

Peacock, Martha Moffitt. “Paper as Power: Carving a Niche for the Female Artist in the Work of Joanna Koerten.” Yearbook of Netherlandish Art History, vol. 62, edited by Ann-Sophie Lehmann, Frits Scholten, and H. Perry Chapman, 238-265. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2012.

Yakel, Elizabeth. “Archival Representation.” Archival Science 3, no. 1 (2003): 1–25.

© Catherine Powell and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Catherine Powell and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments