Whose words are they, anyway? Visiting 'Elizabeth and Mary: Royal Cousins, Rival Queens'

In this blog, Clodagh Murphy reflects on her recent visit to "Elizabeth and Mary: Royal Cousins, Rival Queens" at the British Library. The first exhibition to consider both queens jointly, "Elizabeth and Mary" tells their remarkable story through the queens’ ‘own words’.

Earlier this month, I had the chance to visit the British Library’s blockbuster exhibition Elizabeth and Mary: Royal Cousins, Rival Queens (running until 20 February 2022). The exhibition is a unique opportunity to see a dazzling array of treasures associated with the queens and their relationship, such as the breathtakingly intricate ‘Marian Hanging’ embroidered by Mary during her long imprisonment in England, Elizabeth’s locket ring, which contains portraits of her and her mother Anne Boleyn, and the Penicuik Jewels, given away by Mary at her execution and preserved in her memory.

But it was the decision to tell the queens’ story through their own words that most piqued my interest. As John Guy points out in the exhibition catalogue, Elizabeth and Mary never met (despite doing so on screen, such as in Josie Rourke’s 2018 Mary Queen of Scots): instead, they ‘were forced to conduct their relationship through their letters or the speeches of their ambassadors’ (Guy 2021). Lead curator Andrea Clarke explains that ‘these thrilling documents, written in the queen’s own hands and in their own words’ therefore ‘form the narrative backbone of the exhibition’ (Clarke 2021). But what, exactly, are these queens’ ‘own words’? We know that documents such as letters might have been drafted by or devised alongside secretaries, and that one cannot therefore assume that words written in the queens’ hands or names are always their own unmediated compositions. This problem is central to my own research in the FEATHERS project, examining secretarial influence on Elizabeth I’s English scribal letters.

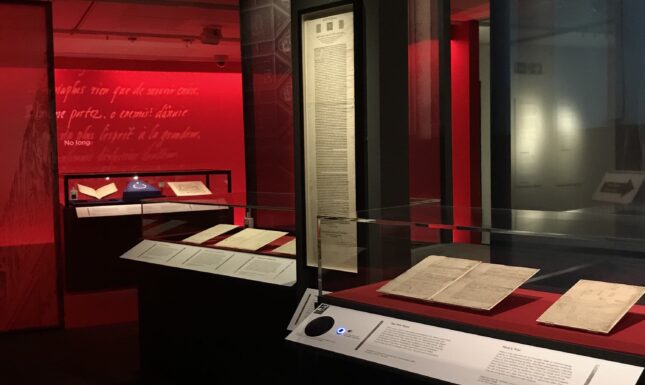

A stunning array of texts are on display, many drawn from the British Library’s own extensive manuscript collection, and others on loan from other institutions such as the National Archives. The chance to encounter such historically important documents, such as Elizabeth’s ‘Tilbury Speech’ and the ‘Tide Letter’, in their original manuscript forms is thrilling, and in doing so the visitor can often see the queens’ words in the process of being shaped. The autograph drafts of Elizabeth’s 1563 and 1567 speeches to parliament are on display, and her working copy of her 1586 speech, written in a scribal hand with edits by the queen, provides a glimpse into the often collaborative nature of textual production.

Elizabeth and Mary brings these words to life. They are amplified visually: quotations are displayed on the walls of the exhibition space, serving as miniature transcriptions and narrative signposts, such as Mary’s plea to Elizabeth ‘I am your cousin, the closest you have in the world’.

The queens’ voices are amplified aurally, too: via a hands-free speaker, I listen as ‘Mary’ informs Elizabeth of her arrival in England, and hear Elizabeth announce her ‘heart and stomach of a king’ to another visitor further along. The desire to not be heard is exhibited, as well: Mary’s ciphered letter to the Duke of Norfolk (with whom she conspired to marry behind Elizabeth’s back) is on display, as is the ‘Babington’ cipher, the fatal decoding of which caught Mary in the act of treason and facilitated her execution. The cipher is decoded and explained to the visitor through a digital display, granting them access to this deliberately (but ultimately unsuccessfully) inaccessible text.

Although uplifted, Elizabeth and Mary’s words are not untethered or isolated: on the contrary, they are richly contextualised by those of others. The queens’ writings are displayed alongside those of ambassadors and secretaries, in which the queens are discussed and through which they might themselves speak: Mary’s passionate declaration that ‘we be both of one blood, of one country, and in one Island’ is transmitted to Elizabeth via Sir Nicholas Throckmorton. A memorandum, in which William Cecil considers what to do about Mary’s flight into England, is closely displayed by a letter from Elizabeth to Mary. Pointing out that ‘Elizabeth followed Cecil’s advice’, the label encourages the visitor to ponder how far Elizabeth’s actions—and her words—were informed by her right-hand man. Models of letters in their original, locked forms and videos of the letter locking process (made by Unlocking History) introduce the visitor to the context of epistolary production in which clerks and secretaries were intimately involved. Elizabeth and Mary therefore not only introduces the words of these two remarkable women in interactive, creative, and accessible ways, but invites the visitor to reflect upon the complexity of the contexts in which these words were produced and transmitted, and on the different people and events that shaped them.

The effect of this simultaneous uplifting and contextualisation of the queens’ voices that is employed throughout Elizabeth and Mary is most poignantly felt in the presentation of Mary’s trial and execution. In her response to parliament’s call for Mary’s execution, Elizabeth bemoans the difficulty of her position. In a sketch, Cecil maps out the seating plan for Mary’s trial, and a letter from Elizabeth’s privy council highlights the ambiguous circumstances under which the decision to execute Mary was finally made. Bringing these items together, Elizabeth and Mary expertly highlight the complexity of this event and the different agents that were involved in bringing it to fruition. As I pored over the display, I became aware of a voice tugging at my attention: it is ‘Mary’. Speaking with a subtle French accent, she reads aloud a sonnet in which she laments her fate. Recently rediscovered, this sonnet was written by Mary in her own hand on the eve of her execution. It is set apart from the previous displays and its text, projected in full, scrolls in sync with the recording, which is played on a loop. Throughout the exhibition, Elizabeth and Mary’s words are enriched by the voices of those around them. But here, through this creative installation, it is Mary’s words that are set apart from and rise above the chorus of voices that precedes them, and are granted control of this part of the narrative.

References and Further Reading:

Clarke, Andrea. “Curator’s Preface.” Elizabeth and Mary: Royal Cousins, Rival Queens, ed. by Susan Doran, London: British Library, 2021, pp.6-7. The exhibition catalogue can be purchased here: https://shop.bl.uk/products/elizabeth-and-mary-hb

Dambrogio, Jana, Daniel Starza Smith, Jennifer Pellecchia, Alison Wiggins, Andrea Clarke, Alan Bryson. “The Spiral-Locked Letters of Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots.” Electronic British Library Journal, vol.11, 2021, pp.1-50. This groundbreaking article presents new research on the ‘Spiral Lock’ technique employed by Elizabeth and Mary to lock their letters and discusses the display of Elizabeth and Mary’s letters in the exhibition. https://www.bl.uk/eblj/2021art...

Guy, John. “Introduction.” in Elizabeth and Mary: Royal Cousins, Rival Queens, ed. by Susan Doran, London: British Library, 2021, pp.14-21

FEATHERS project: https://www.universiteitleiden...

Press release: https://www.bl.uk/press-releas...

© Clodagh Murphy and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Clodagh Murphy and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments