Çiğ Köfte and Rosé Wine: Neo-Arabesk Mashups, Guilty Pleasure, and Play

Arabesk music ‘portrays a world of complex and turbulent emotions peopled by lovers doomed to solitude and a violent end’. Saniye Ince reflects on guilty pleasure and play, exploring neo-arabesk, a contemporary Turkish music genre, and its ties to the country’s food culture.

In August 2021, I found myself at my family’s summerhouse in Mersin (Turkey), writing a proposal to apply for my current PhD on play and politics, titled “Ambiguity and escalation: The digital playground of Turkey’s warring secularists and Islamists”. My mother decided to invite all twenty-four of our family members to the house, as we had not gathered since the beginning of the pandemic. In an environment of love, intervention, loud music, loud conversations, drinks, kids, aunties, gossip, and any other source of support and distraction that one could imagine, I had to finalize my proposal.

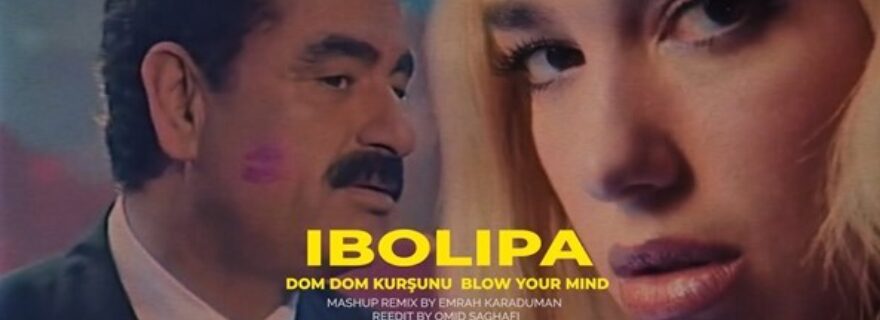

I created a workspace on the backside balcony, which was the least crowded part of the house, despite it being the secret smoking spot for some of my family members. The only way I could focus on writing was by listening to a very specific kind of music: mashups of international pop songs and Turkish arabesk music. My favourite track of this absurd genre was a mashup of Ibrahim Tatlıses’s “Dom Dom Kurşunu” and Dua Lipa’s “Blow Your Mind”, better known as #IboLipa.

Dua Lipa x İbrahim Tatlıses - Dom Dom Kurşunu & Blow Your Mind ( Mashup by Emrah Karaduman ) (Video), YouTube, 26 March 2021“Arabesk is a music of the city and for the city”, according to ethnomusicologist Martin Stokes (1992, 1). As an Istanbulite, I can say that every day in this city can be a struggle; its crowds, chaos, and vastness present themselves to a wanderer as ready-made metaphors for any kind of turmoil one may have within. It is no wonder that a kind of music which “portrays a world of complex and turbulent emotions peopled by lovers doomed to solitude and a violent end”, would blossom in this urban existence, at the time when migration from the peripheries to big cities was at its peak (Stokes 1992, 1).

Arabesk and Pop Wars

Throughout its history, arabesk music has faced pejorative criticism because of its association with poverty, lack of education, and bad quality. As part of reformist cultural policy, until the introduction of private television channels in the 1990s, arabesk music was not featured on Turkish TV and radio (Stokes 1992, Şahin 2014). The only exception to this was the New Year’s Eve nights when one could watch the delightful shows of Gencebay or Kibariye on TRT (Şahin 2014). The arabesk debate in Turkey until the 2000s (or in “old Turkey” as we call it nowadays) was like Adorno’s war on pop culture, but it took a different form.

The relationship between pop and arabesk is too complex and porous to explain succinctly. But in a nutshell, Western-influenced pop music was most often seen as more of a higher art form, while Eastern music was considered as low art unless it was framed in a Western way. Despite my awareness that this view of arabesk belonged to the zeitgeist of old Turkey, and although I find this music brilliant, our collective cultural memory still whispers into my ears that arabesk belongs to a “lower culture”. Hence, I felt “guilty” for enjoying it.

Welcoming Eastern Influences

Eastern influences were ostracized by mainstream media until the release of Işık Doğudan Yükselir: ‘Ex Oriente lux’ (Aksu 1995). After securing the queendom in her Turkish pop monopoly, for the first time, Sezen Aksu introduced overtly Eastern melodies into her music. This beautiful fusion welcomed in different shades of Turkishness. Yet, it was still distant to arabesk, mainly due to its evocation of reformist tropes such as “nation imagined as suffering woman” or enlightenment and civilization (Stokes 2010, 110). It neither fully embraces nor represents the hurting souls of arabesk.

In the last decade, however, there seems to be a new trend of embracing music cultures that had not been socially accepted earlier; arabesk and other formerly belittled genres like ‘fantezi’ have found their way into contemporary popular Turkish music. This neo-arabesk music juxtaposes arabesk-fantezi elements and Western influences. One example of this style is Gaye Su Akyol’s “Pink Floyd’un Dedigi Gibi” (“As Pink Floyd Says”) (2014), which incorporates futurist aesthetics, arabesk-fantezi vocals, psychedelic rock, and quotes from Pink Floyd songs. This kind of music has also found its way into Europe, as is exemplified by Altın Gün, an Amsterdam-based band that fuses Turkish folk and psychedelic rock.

Guilty Pleasure and Play

Contemporary psychedelic rock fusion with arabesk and folk influences seems to be largely enjoyed by Turkish youths and internationally. However, to enjoy a sister branch of the neo-arabesk genre, which includes the arabesk-pop mashups, is labelled as “guilty pleasure” (werner raskolnikov 2021). While Aksoy and Altın Gün’s music is embraced wholeheartedly, this is not the case for arabesk-pop mashups and the music of Lin Pesto, an anonymous artist who makes psychedelic covers of arabesk, fantezi, and pop songs. What distinguishes this branch is that instead of merely incorporating Eastern elements into Western-influenced music, it directly uses the older arabesk-fantezi songs.

Regarding Lin Pesto’s music, a brilliant YouTube commenter said: “I’m drinking rosé wine with çiğ köfte” [1]. This evokes the image of Tatlıses drinking whiskey with lahmacun, which is commonly associated with arabesk, vulgarness, and lack of manners (subzero5, jazzlord, and kris 2001-2003). The analogy between Lin Pesto’s music and pairing çiğ köfte and rosé, namely a signature Turkish dish and a high class drink, refers to the absurdity of juxtaposing two kinds of music that belong to different worlds. Keeping in mind that Tatlıses owns a lahmacun chain which later became a çiğ köfte chain, the switch from lahmacun-whiskey to çiğ köfte-rosé works in line with the change in the perception of arabesk music. The listener takes guilty pleasure out of Lin Pesto’s music, yet they also somewhat embrace this extraordinary fusion by making fun of the absurdity.

I see both neo-arabesk music and the “guilty pleasure” it induces as playful. As play scholar Miguel Sicart points out, “the disruptiveness of play is used to shock, alarm, and challenge conventions” (2017, 15). This music is playful because it juxtaposes two contrasting worlds with inherent tensions. The humorous aspect that derives from this unexpected juxtaposition amplifies the playful. Yet, we cannot enjoy this music freely and comfortably, but feel “guilty” instead, due to the remnants of the reformist teachings, namely that this music belongs to an “uneducated lower culture”. Through enjoying arabesk ironically, we can take a deep breath and declare that we do not like it seriously, hence we are not part of that “lower culture”. It is only seriously loved when it complies with the standards of what is perceived to be acceptable contemporary music. Otherwise, the pleasure we extract from neo-arabesk is only within the realm of play, and even then, it is guilty pleasure.

Neo-arabesk may be read as a kind of political play too, considering how music-along with almost everything else-and politics are interwoven in Turkey. How Sezen lost some of her fans for mildly supporting our current president, “the tall man”, in the earlier days of his reign, and how he recently declared war against Sezen due to some of her lyrics which refer to Adam (yes, Eve’s Adam), are examples among many. Arabesk, the music of turmoil, had its breakthrough at a moment of socio-political crisis. This new way of guiltily embracing and enjoying arabesk does not seem to be too different.

[1] My translation. Original: "Çiğ köfte ile rosé içiyorum.” This comment was lost due to copyright issues on the video, which has since been taken down. The original video was posted to Lin Pesto's YouTube page, August 2021.

References

Aksu, Sezen. 1995. Işık Doğudan Yükselir ‘Ex Oriente Lux’. Pop. Foneks.

Şahin, Çağatay. 2014. ‘Türkiye’de Arabesk Müzik Kültürü ve TRT Sansür Kararlarının Etkisi: “Sen Benim İçimde Bir Korkulu Rüya..”’ Salakfilozof. 2014.

Sicart, Miguel. 2017. Play Matters. Paperback. Playful Thinking. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: The MIT Press.

Stokes, Martin. 1992. The Arabesk Debate: Music and Musicians in Modern Turkey. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Stokes, Martin. 2010. The Republic of Love: Cultural Intimacy in Turkish Popular Music. Chicago Studies in Ethnomusicology. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

subzero5, jazzlord, and kris. 2001. ‘Lahmacunla Viski Tüketmek’. Forum/dictionary entry. https://eksisozluk.com/lahmacunla-viski-tuketmek--54080.

werner raskolnikov. 2021. ‘Ibolipa’. Forum/dictionary entry. Ekşisözlük. https://eksisozluk.com/ibolipa--6853312?p=6.

Yalcinkaya, Can. 2022. ‘Turkish Arabesk Music and the Changing Perceptions of Melancholy in Turkish Society’, February.

© Saniye Ince and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2022. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Saniye Ince and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments