Heroes Are History

When Thomas Carlyle presented On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History it was an instant success. The book has more or less disappeared from the bookshelves, but it’s worth a read, and I’ll tell you why.

In Spring 1847, the American intellectual Henry David Thoreau decided to support his friend Thomas Carlyle, as men in that time were wont to do, by writing a public review of Carlyle’s thought and work. One book of Carlyle’s he particularly admires:

“All of Carlyle’s works might well enough be embraced under the title of one of them, a specimen brick, On Heroes, Hero-worship, and the Heroic in History. Of this department, he is the Chief Professor in the World’s University, and even leaves Plutarch behind.”[1]

I first encountered Mr. Carlyle in Edinburgh, in the National Gallery of Scotland. Carlyle (1795-1881) was in fact a Scottish writer and historian. He was born in a town whose name nobody’s ever heard (Ecclefechan), but he gained such a grand reputation during his life that he died being an influential member of the London elite. In spite of his bucolic desires, he spent most of his life in the City. There Carlyle lectured regularly to an audience of rich Londoners. In May 1840 he delivered his last and most famous series of six lectures, published one year later under the title On Heroes, Hero-Worship and the Heroic in History.

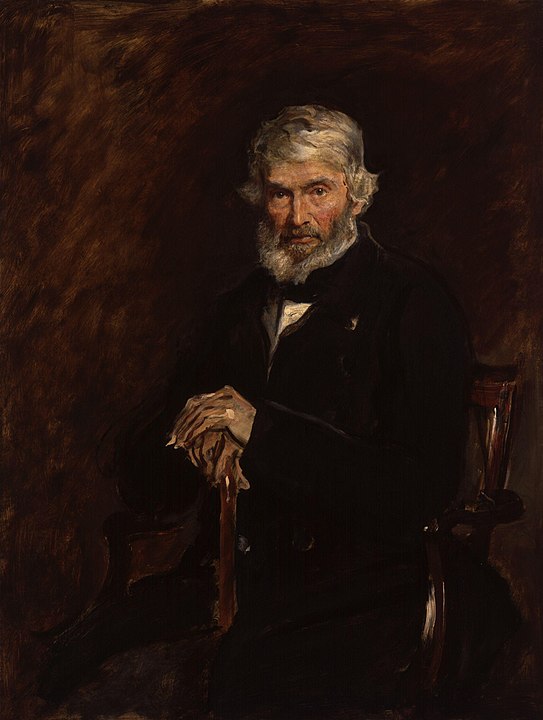

Portrait of Thomas Carlyle by Sir John Everett Millais, now in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Oil on canvas. Picture: Wikimedia Commons

When I met Carlyle, I saw him in a room surrounded by other famous faces of Scotland. His portrait was accompanied by one of his best-known phrases: “The History of the World was the Biography of Great Men.”[2] The sceptic and feminist in me immediately started to rebel when I read this, but at the same time I was struck by the reality of the remark. For is it not so that in official accounts of history, writers tend to focus on the great personalities and their achievements, and often neglect to mention what is normal, everyday, common to all? The tendency to select and ignore — pick-and-choose, so you will — has marked the art of historiography from its beginning. It’s no coincidence that Henry Thoreau compared Carlyle to Plutarch, the most celebrated biographer of ancient Greece. Studying one of the ‘Great Men’ of Antiquity, the politician and writer Cicero, I am on a daily level both annoyed and fascinated by the ancient historians’ focus on a select group of Roman ‘model’ figures, who are seen to possess a highly exclusive set of personality traits and political feats.

Carlyle’s vision on ‘Universal History’, as he calls it — or, as we would probably call it, the Western historical tradition — would be rejected in our modern society on account of more reasons than I care to mention here. However, we must acknowledge that his view has been the view of the intellectual elite for a very long time. Moreover, Carlyle’s work provided a big impetus to the writing of history and biography in the nineteenth century; in his lectures on heroism, he was actually the first to formulate this ‘Great Man Theory’. Though I do not agree with all he says, in his flowery style of speaking and with a surprising acuteness, Carlyle makes some pretty Great Observations.

The London Library. It was Thomas Carlyle who, sick of being unable to borrow books from the British Library, instigated the building of a new public library in London. It was opened in 1841 and still exists. Image by Matt Brown, Creative Commons license.

To understand Carlyle’s Great Man Theory, we must first understand what he understood by ‘great’ or ‘heroic’. In a society increasingly characterized by industrialisation and commercialism, Carlyle went to look for a leader in history who was able to connect with the universal meaning of life. According to him, leaders of this sort had ceased to exist in his own time (with the exception of his personal model Goethe), but the past provided many examples. In order to exert real influence, the ideal leader needed to be worshipped as someone greater than the normal people, which is to say, as a hero. Carlyle distinguishes six types of heroes, who must all possess the crucial quality of sincerity: the Divinity (with Odin, the Norse god, as the main example), the Prophet (Mohammed), the Poet (Dante and Shakespeare), the Priest (Luther, Knox), the Man of Letters (ideally Goethe, but as actual examples he gives Samuel Johnson, Rousseau and Robert Burns), and the King (Oliver Cromwell, Napoleon). For Carlyle, “all sorts of Heroes are intrinsically of the same material”, they need to have “a Great soul, open to the Divine Significance of Life”.[3] To us this may sound a bit whacky, but Carlyle is saying that (heroic) leadership principally flows forth from a spiritual greatness, a greatness of mind. Outward circumstances change, communities fall apart, but people are able to connect with each other by recognizing each other’s genuineness or ingenuity. These qualities manifest itself similarly in all men, in all times. In this regard, Carlyle sees a particular responsibility for the literary man. Admittedly, he is a “rather curious spectacle”, “ruling (for this is what he does), from his grave, after death, whole nations and generations who would, or would not, give him bread while living”.[4] Yet what do they do, these heroes of letters? They write books. Regardless of whether you think that’s a heroic effort in itself (I do), through these books, rather importantly, the past is preserved and with it every thinker that ever lived. In Carlyle’s rhetoric:

“All that mankind has done, thought, gained or been: it is lying as in magic preservation in the pages of Books.”[5]

Carlyle hastens to say that he is not thinking about chick lit (novels read by “foolish girls”), but really this remark nails down the power of literature intellectual or otherwise.

Politically, Carlyle’s theory is a minefield. Especially in his last lecture about the Hero-King, he seems to be pleading for authoritarianism, and he might well be in ways that we, after World War I & II, find difficult to bear. (I personally think that Carlyle’s is alluding here to the Platonic concept of the philosopher-king, but that’s beyond the limits of this blog.) Carlyle’s theory of intellectualism and the belief that erudite men would know what is best for society also awkwardly reminds us of present Dutch politicians.

Thomas Carlyle reading in the garden of his house at Cheyne Row, in London, Chelsea, the place from which he received the name ‘Sage of Chelsea’; he shared his intellectual abilities with famous men such as John Stuart Mill, John Sterling, Charles Dickens, and John Ruskin. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Carlyle, however, was an intellectual more than a politician. This is confirmed by his nickname: the ‘Sage of Chelsea’. He was the Cicero of his day: theorizing, classicizing, imagining the traditions of old to be the proper building blocks for modern society. His chief message is fairly simple: we need leaders who are sincere and inspiring, and who are knowledgeable enough to see the bigger picture or connect past and present. Literary scholars therefore deserve a place in the political hierarchy. Now there’s a thought for those who refuse to invest in the Humanities.

Read more?

L. Hughes-Hallett, Heroes. Saviours, Traitors and Supermen (London: Fourth Estate, 2004); see also the review by Colin Burrow.

F. Kaplan, Thomas Carlyle. A Biography (Cornell Univ. Press: Ithaca, 1938).

J. Morrow, Thomas Carlyle (Hambledon-Continuum: London/New York, 2006).

D. R. Sorensen & B. E. Kinser (ed.), On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History. Thomas Carlyle (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2013).

[1] H.D. Thoreau, Graham’s Magazine, March & April 1847, in: J.P. Seigel, Thomas Carlyle: the Critical Heritage (New York 1971), 298.

[2] D.R. Sorensen & B.E. Kinser (eds.), Thomas Carlyle. On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2013), 30. All quotations are from this edition.

[3] On Heroes, 104.

[4] Idem, 132.

[5] Idem, 136.

© Leanne Jansen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Leanne Jansen and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

1 Comment

It is true that heroes are often the symbol of history and that a 'spiritual' quality ought to be associated with those mortals for the magic to work. Anthropologists often focus on uprooting such spiritual roots in society. In times of significant social and political change communities tend to cling unto the past and the formation of heroes serves the social function of maintaining social cohesion between the generations. Thomas Carlyle grew up in the 19th century, which contained much change (fall of the Spanish Empire, Britain taking over the World's economy, faster communication by steamships, railways and telegraphs, etc.). Mister Carlyle, growing up in a time in which rapid change occurred, witnessed and testified of the 'need' for heroes in human history. A modern version of the formation of heroes is Latin American history after the 1830s in which military figures (both colonial and post-colonial) are selected as 'founding fathers' of nationalistic movements that occurred in the 1950s. Just as in any historical era, the mythology around these heroes are socially constructed to advance political stability.