Medieval Mindfulness

There are some striking similarities between medieval devotional practices and modern mindfulness exercises, especially with regard to the role of the body in meditation.

Hail, o glorious head of our saviour, that, for our sakes, was crowned with thorns and beaten with a reed… Hail, o most honourable hands and arms that, for our sakes, were extended on the cross… Hail, o most holy knees of Christ that, for our sakes, were bended in prayer. Hail, o honourable feet of Christ that, for our sakes, were raised on the cross with blunt nails. [1]

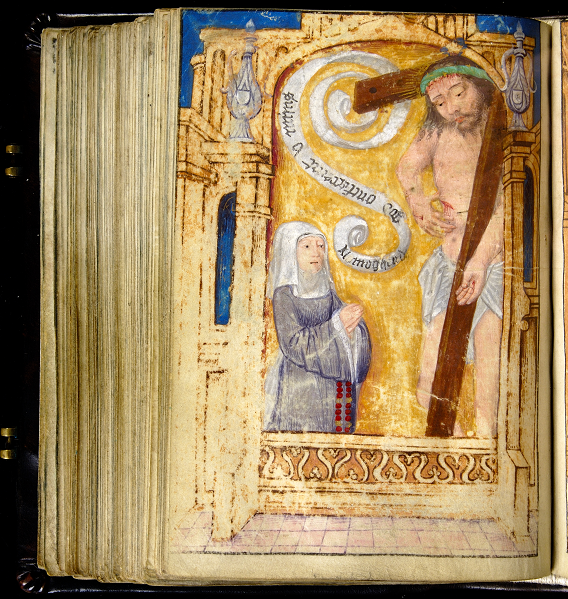

This quotation is part of prayer to Christ's body parts, a type of prayer that was very common in the late medieval period. Christ is decribed from head to toe, paying attention to each part of his body that was wounded during his passion. Prayers about the suffering Christ belong to the realm of affective meditation or piety, a devotional practice in which one is supposed to emphasize and identify with the suffering Christ – the medieval concept of imitatio Christi. Thus, the readers of this prayer did not only think about the suffering of Christ’s body, but also imagined how this would feel if it would happen to their own bodies.

Christ's head in a book of hours, London, British Library MS Harley 5315, f. 83r, Southern Netherlands, 15th century

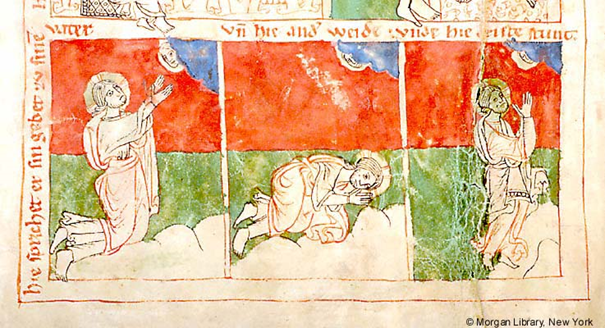

The text speaks of Christ’s knees, bent in prayer. This probably refers to Christ praying to his Father in Gethsemane. The Gospel accounts tell that he prayed three times. According to Matthew and Mark Christ laid prostrate in the ground, and according to Luke he was kneeling. A Bohemian manuscript depicts Christ in three postures: kneeling, lying prostrate, and standing up.

These three images are probably based on the prayer postures that are described in medieval prayer manuals, such as De modo orandi (On the Manner of Prayer). This work, composed around the middle of the thirteenth century, was meant as instruction for Dominican novices and the illustrations show the postures that St. Dominic had used in prayer. To the modern viewer they might look a bit like medieval yoga poses.

St. Dominic in Prayer, De modo orandi, Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana MS Lat. Rossianus 3, Spain, 15th century

Both the prayer texts about Christ’s body parts, and the prayer postures demonstrate the importance of the body in medieval practices of prayer and meditation. While the emphasis on Christ's suffering seems to promote a mortification of the body, it is clear that the body is also seen as something that can be used towards spiritual ends. How do body and mind relate to each other, then? A comparative approach can provide some answers, for descriptions of the body are not only part of the Christian tradition of meditation. Take a look at these fragments from a three-minute guided mindfulness meditation:

Now bring your attention to your head, feeling into your scalp, the forehead, and temples. Observe your eyes, cheeks, your ears, jaw, and chin … now lower your focus to the neck and shoulders … bring awareness to your arms … now come to the chest and torso area … and scanning the legs, the ankles, the feet, and the toes … notice how paying attention to the entire length of the body feels.

This common mindfulness exercise is called the ‘body scan’. Listening to a gentle voice telling you on which body part to focus your attention, you are supposed to be aware of your bodily presence in the moment. While its roots lie in Buddhism, mindfulness is gaining popularity in the West, being not only embraced by the New Age movement but also by modern psychologists who recommend its use in clinical practice to reduce stress and anxiety, among other things.

The body scan exercise was developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn as part of his ‘Mindfulness-based stress reduction’ program. It is based on Eastern practices such as Hatha Yoga and vipassanā. The practice makes you aware of the transitory nature of experience, of the interpreting and judging role of the mind, and while it makes you aware of the presence of your body in the moment, it can at the same time lead to a dis-identification with your own body.

St. Dominic in Prayer, De modo orandi, Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana MS Lat. Rossianus 3, Spain, 15th century

Both the prayers to Christ’s body parts and the prayer postures demonstrate the importance of the body in medieval practices of prayer and meditation. Although the body is something that should be controlled and mortified, there is no dualistic opposition between body and soul: the body is instrumental and can be used towards spiritual ends. One of the ways in which this process could have worked is suggested by modern mindfulness exercises like the body scan: attention to the body can lead to awareness of the transiency of experience, and eventually strengthen the mind.

Woman praying to Christ in the Van Hooff prayer book, University Library Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, XV.05502, f. 133v, Flanders, ca. 1520

Without claiming that mindfulness and medieval Christianity are alike, a comparative approach to spiritual practices can be fruitful. In this case, it enables us to apply the psychological research on mindfulness meditation to medieval practices of prayer and meditation. This helps us to understand how a focus on the body can have a psychological effect that benefits the mind. In both the cases, the body is not neglected, but used to reach a higher state of mind.

Further reading

Leiden Univeristy's Massive Open Online Course 'De-Mystifying Mindfulness'

Bériou, N., Berlioz. J., Longère, J. (eds.), Prier au Moyen Age. Pratiques et Expériences (Ve-XVe siècles) (Trunhout 1991).

[1] Wes ghegruet o gloriose hoeft ons behouders. dat om onsen wille is ghecroent mit doernen ende gheslaghen mitten riede ... Wes ghegruet o alre eerlicste handen ende armen om onsen wille wtgherecket anden cruce ... Wes ghegruet o alre heilichste knyen cristi om onsen wille ghebughet inden ghebede. Wes ghegruet o earlike voeten cristi om onsenn wille mit plompen naghelen gheheft anden cruce. (MS Leiden, University Library, LTK, ff. 36r-38r)

© Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

2 Comments

Yes of course! If you want to publish the essay you probably have to contact the institutions that keep the images.

What is the topic of your essay?

May I have permission to refer to this interesting article in my Birkbeck MA essay and reproduce the illustrations please?