One hundred and eleven drawings identified as the work of Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder

The scoop every project is hoping for.

A Brugean masterpiece

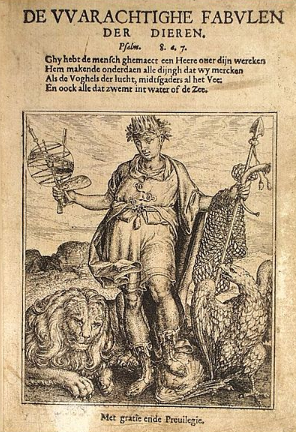

An important item in the source material for the NWO project Aesopian Fables 1500-2010: Word, Image, Education is the 16th-century Brugean masterpiece De Warachtighe fabulen der Dieren (‘The Truthful fables of the animals’, henceforth: TFA). Pieter de Clerck, a rather average Brugean printer, put up his once-in-a-lifetime achievement by publishing it in 1567. The book was a collection of 107 fables, mainly aesopic and each of them illustrated with an exquisite etching. These etchings were all made by De Clerck's townsman Marcus Gheeraerts (Bruges, c. 1520 – London, c. 1590) who also was the initiator and financer of TFA. For the text of the fables Gheeraerts called in his friend Eduard de Dene, in those days one of the prominent writers in Flanders. The cooperation of Gheeraerts, De Dene and De Clerck resulted in something new in Dutch literature: TFA was the first emblematic fable book and even the first homegrown emblem collection in the Low Countries in general.

Fig. 1: title page of TFA (Bruges, 1567). Image: dbnl.org, Ghent University Library, BHSL.RES.0697.

Texts and illustrations: a fascinating twosome

De Dene’s text was not the product of his own invention. For the greater part he gave a rather free version of Les fables d’Esope Phrygien by Gilles Corrozet, published in 1547 (first edition 1542). But he also drew on medieval Natural History encyclopedias and on the emblem collection of Alciato, in this way providing us with the first Alciato translations in Dutch. Another striking novelty was that De Dene, obviously in consultation with Marcus Gheeraerts, linked each fable with one or more biblical passages. It’s surprising and intriguing to notice that these passages are adaptations of verses taken from catholic as well as from protestant bibles. Interesting though the texts of De Dene are, the book undeniably owes its success to the beautiful illustrations. The original copper plates for the etchings did not stay in Bruges. They were sold and ended up in Antwerp and, later, in Amsterdam. So, over the years, several Dutch, French, Latin and German adaptations of TFA were made and the etchings were reused and copied again and again until well into the 18th century, giving rise to a most interesting Gheeraerts filiation.

An unexpected discovery

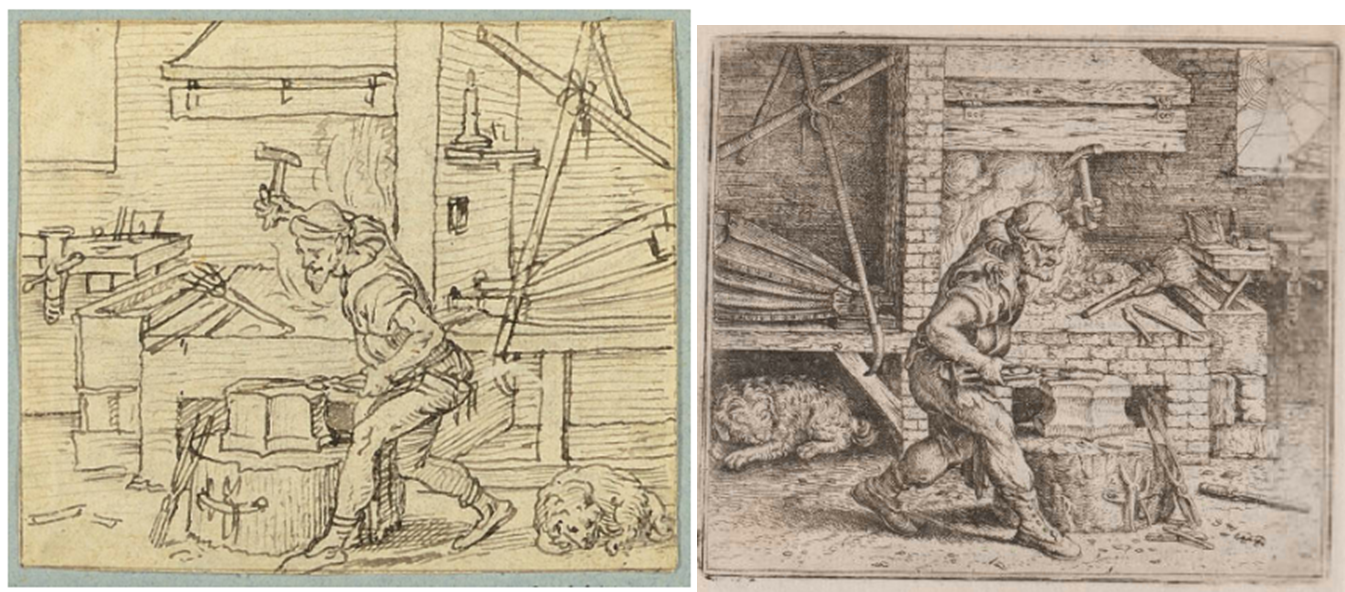

Sometimes you find things because others haven’t looked for them yet. This may put the singularity of what follows into perspective, but it surely doesn’t diminish the importance of it. Anyway, scrolling through the results I got when Googling for images of TFA, I found the online collection of the Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden, offering no less than 111 small drawings (mostly 95 x 110 mm) , all of them described as being drawn ‘nach Marcus Gheeraerts’. Furthermore, 95 of these 111 drawings were characterised as ‘Nachzeichnung einer Illustration in De Warachtighe Fabulen der Dieren (Brügge, 1567)’. To illustrate this, I give two examples (fig. 2a and 2b - left the Dresden drawing, right the etching of TFA):

Fig. 2a: drawing and etching of ‘The smith and his dog’ (TFA, p. 34-35). Drawing: SKD, Kupfer Stichkabinet, C 1941. Etching: Ghent UL, BHSL.RES.0697.

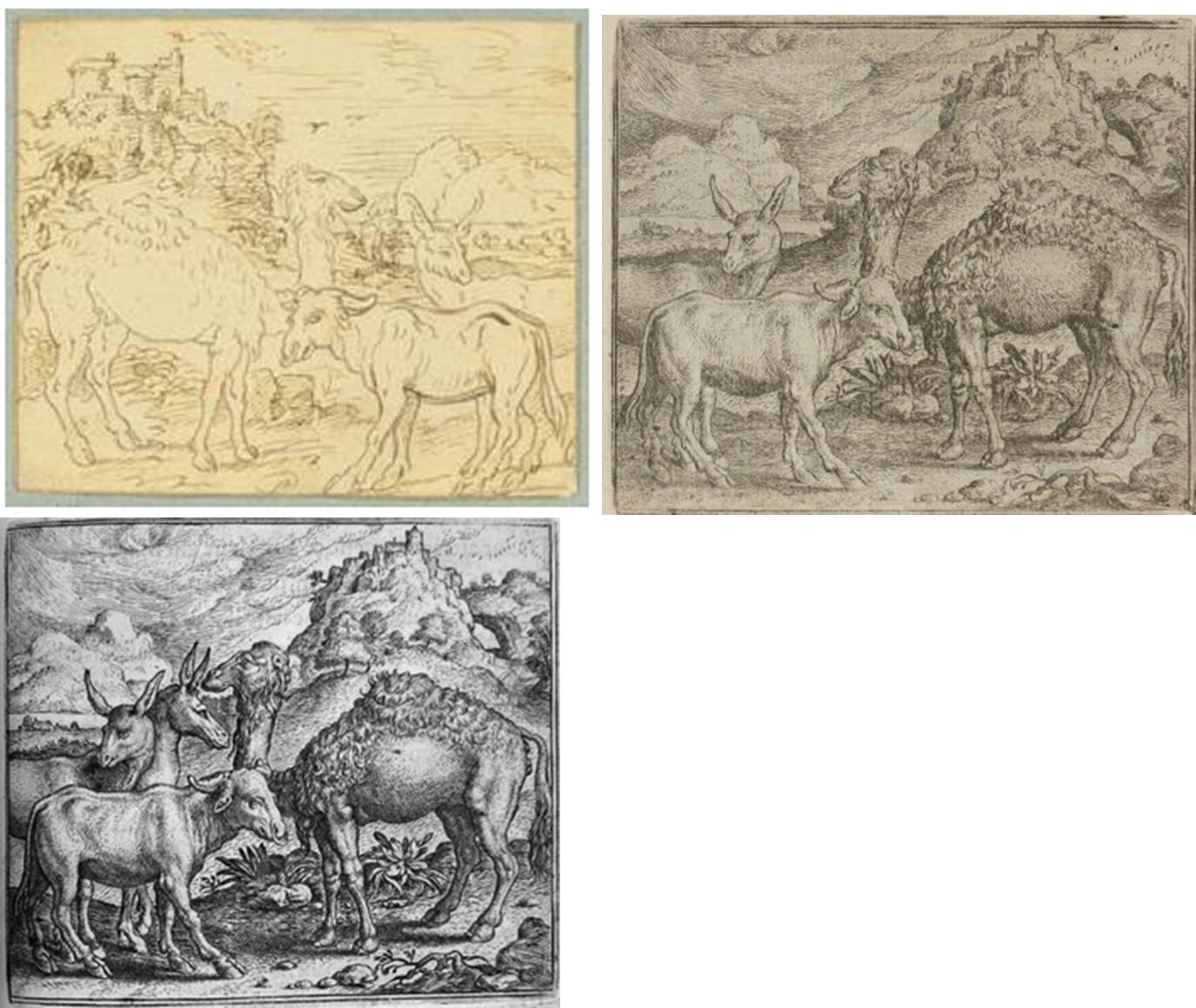

Fig. 2b: drawing and etching of ‘The goat and the wolf’ (TFA, p. 58-59). Drawing: SKD, KS, C 1925. Etching: Ghent UL, BHSL.RES.0697.

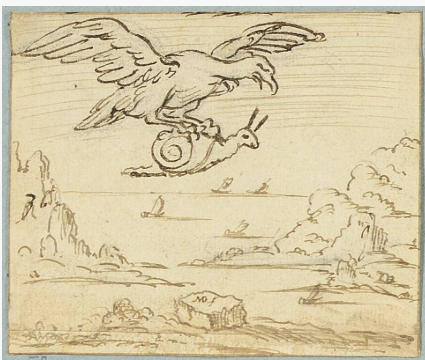

Despite their description on the site, it’s obvious that the Dresden drawings cannot be Nachzeichnungen (copies), because they are all mirror images from the etchings in TFA. The logical result of simply copying the etchings (nachzeichnen) surely would be a non-mirroring drawing. Noteworthy too is that once or twice the drawings show striking differences with what we see in TFA (a different background or a deviant posture of an animal). A third characteristic is that the drawings most probably will not have been made later than 1567, the publishing year of TFA. The ground for this assumption is an eye-catching mistake made by Gheeraerts in TFA. In the illustration of the fable ‘The donkey, the camel, the buffalo and the mule’, we only see three animals, whereas the title and the text mention four. Gheeraerts surely must have felt bad about this and for Esbatement moral des Animaux (Antwerp, 1578), the first adaptation of TFA, he corrected his mistake adding the fourth animal on the original copper plate (fig. 3). A final element in my line of reasoning is provided by the drawing for the fable ‘The eagle and the snail’ (fig. 4). On a small rock at the bottom, we see a letter combination: MG f, undoubtedly meaning Marcus Gheeraerts fecit. Combining all this, and keeping in mind that an etching is always a mirror image of its design, the conclusion can only be that the Dresden drawings are trial sketches or perhaps even the original designs, made by Gheeraerts for the etchings in TFA.

Fig. 3: drawing and etchings of the fable ‘The donkey, the camel, the buffalo and the mule’, with the correction in the 2nd etching. Drawing: SKD, KS, C 1973. Etchings: Ghent UL, BHSL.RES.0697 and Bibliothèque nationale de France, RES P-YE-550.

Fig. 4: MG f in the drawing of the fable ‘The eagle and the snail’. SKD, KS, C 2020.

111 = 95 + 14 + 2 = 750%

As I said before, the Dresden collection holds 95 trial drawings or designs of the 107 etchings in TFA. Besides these, the collection also offers fourteen drawings used for etchings in the Esbatement moral, illustrating fables that do not appear in TFA. The remanining two drawings are designs for title pages. One of them was the source for the frontispiece of Esbatement moral, whereas the other one, as it seems, was never used: it probably was a rejected design for TFA or Esbatement.

As a conclusion we can state without any doubt that the 111 Dresden drawings are quite a catch in the research on Gheeraerts, TFA and Esbatement. They raise new questions on the genesis of TFA and Esbatement and, even more important, they give us a far better view on the skillful artist Marcus Gheeraerts was. Up to now only some fifteen Gheeraerts drawings were known, mainly contributions in the alba amicorum of other humanists. With the Dresden set, we enlarge this amount with nearly 750%. Not a bad unexpected result for the aforementioned Leiden project on Aesopian fables.

Further reading

Hodnett, E., Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder of Bruges, London and Antwerp, Utrecht, 1972.

Schouteet, A., Marcus Gerards, zestiende-eeuws schilder en graveur, Brugge, 1985.

Geirnaert, D. and P.J. Smith, ‘The Sources of the Emblematic Fable Book De warachtighe fabulen der dieren (1567)’, in: Manning, J., K. Porteman and M. van Vaeck (eds.), The Emblem Tradition and the Low Countries. Selected Papers of the Leuven International Emblem Conference, 18-23 August, 1996, Turnhout, 1999.

Smith, P.J., Het schouwtoneel der dieren. Embleemfabels in de Nederlanden (1567-ca. 1670), Hilversum, 2006.

2 Comments

Also really interesting to see that Gheeraerts had originally planned to have an illustration of Aesop. One of the interesting things about de Warachtighe Fabulen is that he rejected this traditional image and instead shows man's sovereign dominion over the inferior creatures (Psalm 8).

What a fantastic scoop. Very well done. I've often wondered if we'd ever see them. Hodnett mentions that they'd last been seen in 1868, when they were sold at auction in Paris. I hope to see them in the flesh sometime.