The Cat in Medieval Western Europe

How come cats were worshipped in ancient Egypt and reviled in medieval times? It seems that the spread of Christianity is to be blamed. Fortunately for the cat, the feline folklore is still going strong.

With the start of the Viking raids in the eight century, cats became a rare phenomenon in early medieval western Europe, boosting their status. Because rural and urban areas still required protection from rodents contaminating their food, cats were especially valued for their mousing skills, so much so that laws were established laying out the duties of the cat and standardising its monetary worth. The tenth-century Laws of the Welsh King Hywel Dda specified the value of a cat as follows: “The value of a cat, fourpence. The value of a kitten from the night it is born until it opens its eyes, a legal penny; and from then until it kills mice, two legal pence; and after it kills mice, four legal pence”.[1] To compare, full-grown sheep or untrained house-dogs were also valued at fourpence. Furthermore, “her properties are to see and hear and kill mice, and that her claws are not broken, and to rear kittens; and if she is bought, and any of those is wanting, a third of her value is to be returned”.[2] It was also important that the cat did not go caterwauling every moon and did not bear burn marks. The social position of the cat’s owner also played a role. For instance, cats who protected the king’s barns were ‘four-legged civil servants’ and should therefore be protected.

The hardship that befell cats in medieval western Europe was a result of the Christian practice of dehumanising and demonising religious opponents, both human and animal. When Christianity began to establish itself as the pre-eminent religion of Europe, pagan beliefs were no longer tolerated. Pagan religions, female-driven worship, and numerous gods and goddesses challenged Christianity. Christian missionaries tried to interlace their religion with established cultural traditions and alternative belief systems (syncretism), such as the cults of Diana and Freyja. However, merging disparate belief systems was not always successful. Whereas some pagan beliefs were able to find a place in Christianity, other gods and goddesses were demonised. Among them were deities associated with cats. As a result, cats found themselves in the middle of a clash between cultural beliefs and became subjected to a multitude of cruelties.

The gradual demonization of pagan deities and the rise of Christianity led to a significant change in attitudes to cats throughout Europe. However, despite the eradication of pagan religions, these religions continued to be practiced in secret, especially in rural areas. When eastern Britain became Christianised, many Romano-British people fled to Cornwall, Wales, or Brittany in northern France. It is precisely in these regions, especially among the peasantry that the respect for the cat survived. Consequently, the European folklore of cats, based on ancient Greco-Roman and Egyptian traditions, was preserved.

Geography, ideology, and social institutions all influence the history and folklore of a culture. The cult of the cat is striking because many of the cat’s pagan associations have found their way into modern European folklore. Furthermore, the feline teetered on a cultural precipice in that it symbolised opposing forces: domestic and wild, natural and supernatural, good and evil, dependent and independent, innocent and promiscuous, nocturnal and diurnal, lazy and vigilant. Associated with all these conceptual categories, cats found themselves in a constant state of liminality. Cats caused conceptual tension. Medieval society reflected the dichotomy of this love-hate relationship and preferred to impose the role of animated mousetrap on the cat. Unsurprisingly, cats can never be truly domesticated due to their highly independent nature and disregard for human rules. This behaviour made people anxious because cats seemed to be overstepping their position in the human-animal hierarchy.

In times of religious upheaval and social uncertainty, ambivalence, which characterised the symbolic understanding of cats, was rarely tolerated. Cultural anxieties were influenced by war, plague, famine, and rebellions. Alternatives had to be dealt with. Therefore, everything outside the norm, like cats, was marginalised. In Greco-Roman times, the animal was deemed to have a sensitive soul and humans were the only ones with a rational soul. This view changed in the early Middle Ages: the Church Fathers then believed animals had no soul at all. However, from the twelfth century onwards, medieval society became more lenient towards the human-animal divide. Due to a renewed popularity of some classical texts (e.g. the rediscovery of Aristotle), medieval people were portrayed alongside animals again.

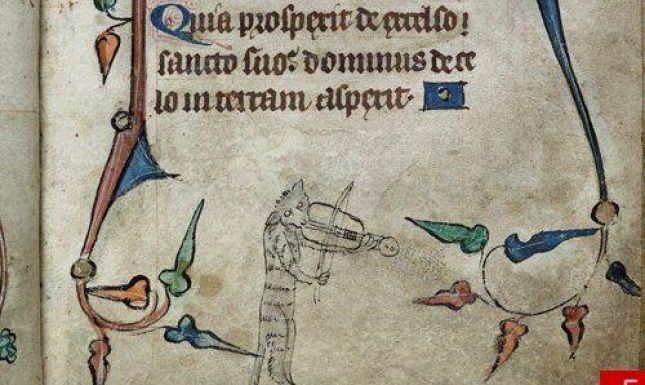

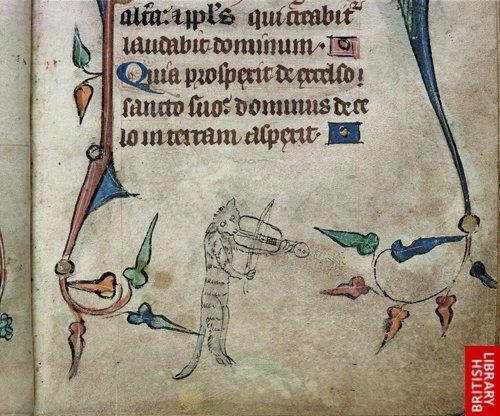

Unfortunately, these portrayals were not necessarily positive. One of the ways people define their identity is by comparing themselves to everything they are not. The combination of several conflicts in the Middle Ages yielded an environment where people needed scapegoats to preserve some sense of social order. Animals, and in this case the cat, became a screen on which medieval people projected their fears and emotions. It is curious that those people who were often in the presence of animals are the exact same people who employed animals as scapegoats. Animals were not rare and yet they seemed to be the perfect mirror image for human society. Medieval people did not only attribute symbolism to animals, but also human characteristics, actions, feelings, and thoughts. The idea was that by projecting human behaviour on animals, it would be easier for people to recognise desirable and less desirable characteristics. Sadly, people were more inclined to project less desirable qualities onto animals. At times, there was also a contrast between domestic and wild animals in which the first often assumed human guilt and the latter personified human shortcomings. Needless to say, since the cat belonged to both the domain of the domestic and the wild, the feline became a popular scapegoat.

Further Reading

Katherine M. Briggs, Nine Lives: The Folklore of Cats (Dorset Press, 1988).

Esther Cohen, “Animals in Medieval Perceptions: The Image of the Ubiquitous Other,” in Animals and Human Society: Changing Perspectives, edited by Aubrey Manning and James Serpell (Routledge, 1994), 76.

Joyce E. Salisbury, “Human Beasts and Bestial Humans in the Middle Ages,” in Animal Acts: Configuring the Human in Western History, edited by Jennifer Ham and Matthew Senior (Routledge, 2014), 10.

Footnotes

[1] Dafydd Jenkins, The Law of Hywel Dda: Law Texts of Medieval Wales (Gomer Press, 1986), 180. Because of the size of Wales, Hywel’s law was formulated in three separate codes: Venedotian, Dimentian, and Gwentian.

[2] Jenkins, The Law, 180.

© Johanna Feenstra and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Johanna Feenstra and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

0 Comments