The sound of silence: WW II memory in present and past

In her research, Yra van Dijk works on memory culture and digital memory of the Shoah. In the context of our 'Arts in Society' theme, she discusses the difficulties around remembrance as 4 May (Dutch Remembrance Day) approaches.

On the moment of writing this blog, (May 1st) the Holocaust Remembrance Day has started at sunset in Israel. Apart from the usual ceremonies and rituals, a new medium of memory culture was launched today: on Instagram. ‘Eva’s story’ is an expensive fictionalized account of the real thirteen-year old victim Eva Heymann.

Still from Eva’s story on Instagram. Created by Mati Kochavi and Maya Kochavi.

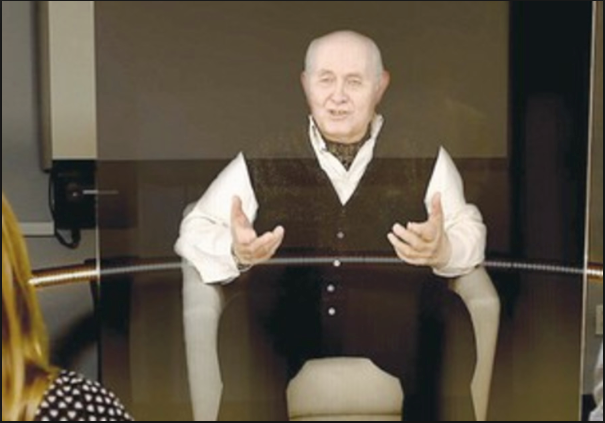

We can argue long and hard about such anachronistic attempts to inform a new, digital-born generation about the horrors of the Holocaust. Bringing the dead to life, as happens even more explicitly in the rather spectral project of the holograms of victim testimonies that can be interviewed in California in a USC-project. There is a lot to say for this: the young will have the impressive experience of hearing survivors about Jewish life and death under Hitler’s regime.

The hologram of a survivor in the USC -project

However, the claim made by the hologram developers that the ‘dialogue continues’, illustrates what is problematic about such projects too: the holograms create the illusion that an algorithm can produce a real dialogue. In the academic discussion about ethics and esthetics of such projects, we need to take the risk into account that new generations will have trouble discerning truth from fiction, the digital archive from reality, and a screen presence from true affect. What does it mean that we can all lay virtual flowers at the virtual graves of individual Dutch fallen soldiers at the website of the Dutch Parliament?

Memory studies, that much is clear, is a fascinating, lively and interdisciplinary field. A framework of history, sociology, media studies and cultural analysis is needed to truly understand what such new performances of memory do and what they mean. 'Memory is never pure', writes James Young: 'never shaped in a vacuum'. Although nothing might seem more simple and straightforward than a nation or a group remembering their fallen or their heroes, commemorating their wars won and their wars lost, it is an intricate and highly political affair, revealing a great deal about the culture that it produces.

The topic is highly political and highly painful, as was also demonstrated today in another news item (the ubiquity of news on the memory of WW II almost 75 years ago is astonishing in itself). The text on this monument in Amersfoort was changed today: the words ‘they sacrificed’ replaced by the more neutral ‘we remember them’, after it turned out that amongst the 20 executed there commemorated, there were two collaborators of the Nazi's.

Memory is not only never pure, it also never sits still: it is dynamic and tells us more about the needs of the present than about the past. All the more interesting that for sixty years now, Leiden University has held on to the commemorative tradition established in the fifties around professor Cleveringa.

As a founding myth of this institution, Cleveringa’s brave speech in 1940 against the suspension of his Jewish colleague professor Meijer, is still pivotal in the academic year. On November 26th there are no afternoon classes and a yearly Cleveringa-lecture is given by a yearly Cleveringa-professor. In a university that presents itself a ‘Bastion of Freedom’, this need not surprise us.

What is remarkable, however, is the silence around the Jewish victims of the war and the Holocaust. Besides the attention for Leiden University heroes like Ton Barge and Ben Telders, and besides the glass stained windows that were erected in more general remembrance of resistance during the war, there is no attention for the murder of staff, students and alumni of our institution. In 1950, a list of 664 victims (including alumni) was compiled in a booklet: In memoriam 40-45. The library has a modest two copies of this list.

In the fifties, the focus on resistance and freedom was part of a nation in reconstruction. We had very little attention for the German and Japanese concentration camps and for the genocide that took place there. This changed, however, and in the seventies and eighties the Dutch joined in the international focus on the horror of the Holocaust after television series and books started to appear.

Holocaust, 1978

This international gulf of remembrance and trauma culture seems to have missed the Rapenburg altogether. Not so much as a plaque was erected for the victims, apart from a small stone in the library for two members of the library staff.

The question today would be, of course, whether it makes sense to correct that hiatus in our institutional memory, and how? A plaque with names set in stone, as the Amersfoort case goes to show, all too often leads to involuntary exclusion and to contested memory. And do we want this belated sign of memory at all?

PhD researcher Adrienne Baars (LUCAS) is doing what first needs to be done: researching and digitalizing the existing list of names to see whether more information on ‘our’ victims can be found by linking digital archives such as the database of Oorlogsgravenstichting and the digital joodsmonument.nl.

And as of 2020, there will be a yearly commemoration in the Academiegebouw on May 4th, as advised by the ‘Committee University Memory culture’. We will hear the story of a single student or staff member who did not survive the war, have a student contest and listen to a yearly commemorative lecture on contemporary research of war and conflict. The option of a digital monument is still being discussed.

Even the institutional memory of the oldest university in the country seems to be open to the demands of a new age for a more inclusive memory culture. That this is a very slow process indeed, is shown when the tags ‘herdenken’ or ‘Tweede wereldoorlog’ have no result whatsoever on the Leiden university website, whereas the tag ‘Cleveringa’ still has 62 hits. Heroes will be heroes.

Literature:

Jeffrey Shandler Holocaust Memory in the Digital Age.

Andrew Hoskins (ed.), Digital Memory Studies. Media pasts in Transition. 2018.

O. Grau, W. Coones, V. Rühse (eds), Museum and Archive on the Move. Changing Cultural Institutions in the Digital Era, , Berlin–Boston: De Gruyter, 2017

James Young: The texture of memory: Holocaust memorials and its meaning. Yale University Press, 1994.

© Yra van Dijk and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2019. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to the author and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

6 Comments

Thanks, Ethan, I will put both on my reading list. Good material for our students of Dutch culture, too!

Thanks for your reply Yra,

In response to your question regarding literature on the Japanese occupation of Indonesia, as a matter of fact I have just published a book on the subject myself: "Japan's Occupation of Java in the Second World War: A Transnational History" (Bloomsbury, 2018). Distinctive to my book is the focus on the wartime Japanese-Indonesian interaction and its ambiguities and repercussions. The focus here is on history rather than memory, and I pay relatively less attention to the Dutch side of the story, one reason being that even as the Dutch (and the Leiden) story in the Netherlands Indies gets much less attention around this time of year than what happened in Europe, it still receives proportionately much more attention than the Asian side of things. When they get any attention, as Rudy Kousbroek once so succinctly put it, the wartime Japanese are treated in conventional Dutch histories as "black boxes," cruel and brutal robots without any feelings or differentiation, let alone any historical context. On the memory question, there is an older book edited by Remco Raben I would call your attention to, one that is extremely original and distinctive in its format: "Representing the Japanese Occupation of Indonesia" (Waanders 1999). This book looks at representations and memory of the occupation as depicted from three sides: Indonesian, Japanese, and Dutch.

Thanks for your reply Yra,

In response to your question regarding literature on the Japanese occupation of Indonesia, as a matter of fact I have just published a book on the subject myself: "Japan's Occupation of Java in the Second World War: A Transnational History" (Bloomsbury, 2018). Distinctive to my book is the focus on the wartime Japanese-Indonesian interaction and its ambiguities and repercussions. The focus here is on history rather than memory, and I pay relatively less attention to the Dutch side of the story, one reason being that even as the Dutch (and the Leiden) story in the Netherlands Indies gets much less attention around this time of year than what happened in Europe, it still receives proportionately much more attention than the Asian side of things. When they get any attention, as Rudy Kousbroek once so succinctly put it, the wartime Japanese are treated in conventional Dutch histories as "black boxes," cruel and brutal robots without any feelings or differentiation, let alone any historical context. On the memory question, there is an older book edited by Remco Raben I would call your attention to, one that is extremely original and distinctive in its format: "Representing the Japanese Occupation of Indonesia" (Waanders 1999). This book looks at representations and memory of the occupation as depicted from three sides: Indonesian, Japanese, and Dutch.

Thanks Ethan, for this 'addition'. That your comment should appear here as some kind of a footnote is iconic for Dutch historiography. I am sorry that I joined in the single-voiced chorus here. Do you know of any literature about the Indonesian side of the Japanese occupation?

Interesting that Leiden does remember the Asian part of WWII with the Japanese soldier, engraved in the window of the Academygebouw, as you pointed out to me.

Important points are made here, but I would like to offer two comments: Firstly, that there is more missing from Leiden's commemorations--and indeed the Dutch national WWII commemorations--than what professor van Dijk rightly highlights. The first is the place of the Netherlands Indies in this story. Many of the Leiden casualties of the war listed in the memorial book that Prof. van Dijk refers to indeed died in Japanese prison camps. But ironically, those listed in the book are limited only to those at the top of the Dutch colonial racial hierarchy of the time. Meanwhile, both here and in national memorials, some 4 million Indonesian casualties of the war--at the time still Dutch colonial subjects--remain unmentioned and unremembered. This highlights the ironic situation of the colonial Dutch in Indonesia at the time (including many Leiden graduates) as both victims and victimizers, treated in a racist fashion by the Japanese while also presiding over, and profiting from, a racist colonial order of their own. Secondly, as bad as conditions in the Japanese prison camps in the occupied Netherlands Indies were, it is misleading and counter-productive to equate them with the Nazi death camps, using the term genocide for both. Arguably, the Japanese did commit genocidal violence in world war two--but not against European colonials or allied POWs. Rather, they did so in China during the 8-year long Sino-Japanese War, where Chinese casualties are estimated at 9 million or more.

Important points are made here, but I would like to offer two comments: Firstly, that there is more missing from Leiden's commemorations--and indeed the Dutch national WWII commemorations--than what professor van Dijk rightly highlights. The first is the place of the Netherlands Indies in this story. Many of the Leiden casualties of the war listed in the memorial book that Prof. van Dijk refers to indeed died in Japanese prison camps. But ironically, those listed in the book are limited only to those at the top of the Dutch colonial racial hierarchy of the time. Meanwhile, both here and in national memorials, some 4 million Indonesian casualties of the war--at the time still Dutch colonial subjects--remain unmentioned and unremembered. This highlights the ironic situation of the colonial Dutch in Indonesia at the time (including many Leiden graduates) as both victims and victimizers, treated in a racist fashion by the Japanese while also presiding over, and profiting from, a racist colonial order of their own. Secondly, as bad as conditions in the Japanese prison camps in the occupied Netherlands Indies were, it is misleading and counter-productive to equate them with the Nazi death camps, using the term genocide for both. Arguably, the Japanese did commit genocidal violence in world war two--but not against European colonials or allied POWs. Rather, they did so in China during the 8-year long Sino-Japanese War, where Chinese casualties are estimated at 9 million or more.