Writer-Heroes and Women Readers

Why do we want to know an author's identity? And what problematic consequences does the notion of the 'writer-hero' have for the literary canon?

This January, the Dutch poet Ester Naomi Perquin was chosen as Dichter des Vaderlands: Poet Laureate, literally Poet of the Fatherland. This unofficial title was created in the year 2000 by the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad, the Nederlandse Programma Stichting and the foundation Poetry International, and the position has been held so far by four men and two women (Perquin included).

During the year 2016, the Netherlands also knew a self-proclaimed Lezeres des Vaderlands (Woman Reader of the Fatherland). This Woman Reader remains anonymous, as she declares on her blog:

I’m a forty-year-old woman with a cigarette. I’m a student. I’m a grandma with a smartphone. I’m an artist, an academic, a writer, a volunteer, a dentist, a musician, a tram conductor.

It doesn’t matter what I am.

The Woman Reader, who stopped this January, aimed to represent middle-aged women, a demographic category that is supposed to consume culture, while nobody cares about their opinion. She lashed out at the literary reviews in Dutch and Flemish newspapers and magazines, which are often written by men about male authors. Moreover, she criticized the reviewers’ idolization of the Big Three as universal norm for all literature: the three Dutch post-war authors Willem Frederik Hermans, Harry Mulisch and Gerard Reve. The Woman Reader employed a statistical method, using the hashtag #lekkertellen (#justcounting) to share her results. Her call for diversity received both approval and criticism.

Sylvia Quiël, bronze portrait W.F. Hermans, Public Library Amsterdam (source)

On her blog, the Woman Reader also shared her view on current events related to literature. One of those events was the revelation of the identity of Italian author Elena Ferrante by journalist Claudio Gatti last October. Elena Ferrante is a pseudonym and the author wishes to remain anonymous – just as the Woman Reader. Gatti’s deed gave rise to critical reactions, also from the Woman Reader, and led to a discussion about anonymous authorship, gender and processes of canonization.

Elena Ferrante's 'Neapolitan Novels''

In an article in the Guardian, Deborah Orr criticized Gatti’s unmasking of Elena Ferrante as an anti-feminist action:

There is a long tradition of women writing under pseudonyms, precisely because of the expectation of private domesticity that has bounded the lives of women. […] Yet, actually, successful women are still expected to account for their ability to balance work and home. […] This is the way in which Gatti thinks Ferrante should be held to account – checked over, to see if her creative life is a suitable match to her domestic life. [...]

Maybe, in general, public life has always been dominated by men, because men crave public acknowledgement more than women do. […] We understand that the achievements of women have been written out of history, and it feels unfair, because that lack of paraded achievement was for so long used against women, as proof that they lacked ability.

In the last part of this quote Orr refers to the (literary) canon, of which women are in many cases left out. This critique is shared by Ferrante herself and is one of the reasons she chooses to write under a pseudonym. In an interview she explains:

The media simply can’t discuss a work of literature without pointing to some writer-hero. And yet there is no work of literature that is not the fruit of tradition, of many skills, of a sort of collective intelligence. We wrongfully diminish this collective intelligence when we insist on there being a single protagonist behind every work of art.

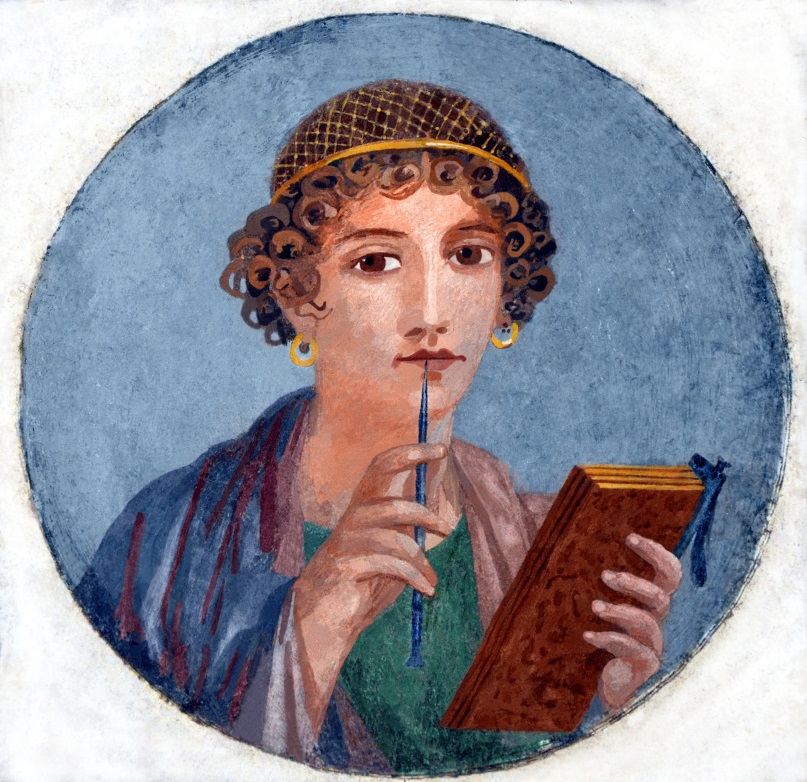

Woman with wax tablets and stylus (so-called ‘Sappho’), fresco discovered at Pompeii, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli, photo by Carole Raddato (source)

Ferrante voices an often-heard feminist critique on processes of canonization. The notion of the romantic Great Artist as Genius excludes many women form the canon. This is problematic because it influences which authors get published, reviewed and read now, as the Woman Reader shows, but it also determines the canon of our literary history.

When we look at the Middle Ages, for example, we can see the results of these canonization processes. It is an interesting period to study in this respect because many authors are, to us, anonymous. The website literatuurgeschiedenis.nl gives an overview of the literary history of the medieval Low Countries in 20 chapters. Only two chapters carry the name of an author, both men: Hendrik van Veldeke and Jacob Maerlant, while a third chapter discusses the work Van den vos Reynaerde, the authors of which identifies himself as ‘Willem’.

Hadewychlaan, Leiden (The Netherlands), photo by ‘Vysotsky’ (source)

Women writers are most prominent in the chapter on Brabant mysticism. This chapter includes the mystic Jan van Ruusbroec, who is second on the list of most translated authors writing in Dutch (after Anne Frank), and two women: Beatrijs of Nazareth and Hadewijch. Hadewijch is an interesting case because we know, besides her name, almost nothing about her identity: it is thought that she was a beguine, but she can also have been a nun; she probably wrote around the middle of the 13th century, but it can also have been 1300. Scholars have made so far not very successful attempts to identify Hadewijch with persons mentioned in historical sources, such as the mystic and heretic ‘Bloemardinne’. The continued interest in and search for Hadewijch’s identity can partly be seen as a symptom of scholars’ desire to get to know the ‘writer-hero’.

Another effect of canonization is that anonymous works often fall outside the canon. Scholars estimate that 70-80% of the Middle Dutch literature consisted of spiritual prose, and comprised prayer books, meditations, and retellings of the life of Christ. Many of these are anonymous texts. Moreover, they do not always meet our modern notions of what literature is. While these texts are studied more and more, they are not well known to a broader audience. The same faith is reserved for many texts that are translations or adaptions, and thus part of a collective effort instead of one brilliant genius.

Mary of Guelders reading, Berlin State Library Ms Germ. Quart. 42, f.19v (source)

Is there a solution for the exclusive mechanisms of canonization? Should we expand our literary canon by including, for example, more women and anonymous texts, or reject the notion of a canon altogether because the principles on which it is based are inherently exclusive?

A solution suggested by the study of medieval texts, and with which the Woman Reader and Elena Ferrante would perhaps agree, is to shift the focus from author to reader. For the medieval period, a reader-centred approach seems natural when we take into account manuscript culture: instead of one standard text we have many manuscripts containing variants of texts. These manuscripts provide little information about the authors, but do often contain physical traces left by readers. This leads to the questions of how these texts were read, by whom, and in what contexts.

Moreover, a reader-centred approach allows for multiple parallel readings of a text, and urges us to be critical of our own reading, since we, as readers, are responsible for which books we read and how we read them.

© Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2016. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lieke Smits and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

2 Comments

Interesting thought indeed, Amaranth! Some women writers still prefer to use initials instead of their first name, such as J.K. Rowling. And the gender reversal through a pseudonym can even be the other way around, e.g. Suzanne Vermeer.

Interesting blog, Lieke. When I was a student 25 years ago, we were not even allowed to discuss the author. At the time, it was all about the text, the text and nothing but the text. I suppose each angle has its advantages. The notion of the reader of medieval manuscripts is thrilling, as Umberto Eco's In the name of the rose has proven. By the way, have you ever wondered how many canonical texts may have been written by women under a man's name? No one can tell, of course, but it's an interesting thought.