A Theatrical Whodunit II: Was this Sherlock mistaken?

In the second instalment in the hunt for the source of the Dutch translation of Calderón’s ‘La vida es sueño’, I will consider an alternative source that might have been used by Schouwenbergh for his Dutch translation made in Brussels in 1647.

In the previous blogpost, I hypothesized that the anthology Doze comedias might have been the specific source for the Dutch translation of Pedro Calderón de la Barca’s La vida es sueño. It was not only printed in 1647 in Lisbon, but the printer Paulo Craesbeeck was also of mixed Flemish-Portuguese descent. Moreover, six other plays in this collection of plays were also translated in Dutch.

Yet, I did not mention that three plays were likely translated with the use of a French intermediary text, which complicates the hypothesis of the previous blogpost:

Amsterdam

- Calderón, El galán fantasma (1637); translated by Simon Engelbrecht and adapted by David Lingelbach as De spookende minnaar (1664);

- Calderón, La dama duende (1629); adapted by Andries Peys as De nacht-spookende joffer (1670) and another time by Lodewijk Meijer as Het spoockend weeuwtje (1670).

Brussels

- Alonso de Castillo Solórzano, El marqués del Cigarral (before 1647); translated and adapted by Claude de Grieck as Don Japhet van Armenien (1657).

Calderón’s La dama duende was translated twice: once by Andries Peys and another time by Lodwijk Meijer in the same year. Peys’ version gives no indication that a French intermediary text was used, but Meijer explicitly mentions in the foreword that he looked at the French source; he even regarded the play to be originally French. The same applies to Lingelbach’s adaptation of El galán fantasma. Likewise, it is stated in the foreword that Engelbrecht translated the play from French.

A bigger problem is, however, that Castillo Solórzano’s El marqués del Cigarral was possibly also translated with the use of a French intermediary text. According to the title page of the oldest surviving print of De Grieck’s Don Japhet van Armenien, it was translated after Paul Scarron’s Dom Japhet d’Armenie (1653): “Uyt het Frans van den HEER SCARRON”. Furthermore, the Amsterdam printer Dirck Cornelisz Houthaeck says in the foreword that he asked the playwright Jillis Noozeman to check the text of De Grieck against Scarron’s French text, because the Brabant dialect is different from the dialect spoken in Holland.

This means that we are left with a text that the printer purposely influenced by comparing it to Scarron’s version. That is not to say that De Grieck also actually used Scarron’s version of the play for his own translation. It is indeed possible that he did this, since De Grieck lived in Brussels and although Belgium’s capital city was still largely Dutch-speaking in the seventeenth century, French increasingly became an important cultural language as well. Therefore, the direct link between Brussels and the anthology printed by Paulo Craesbeeck is unsettled in the air again, although we know that De Grieck has, in fact, also translated directly out of Spanish.

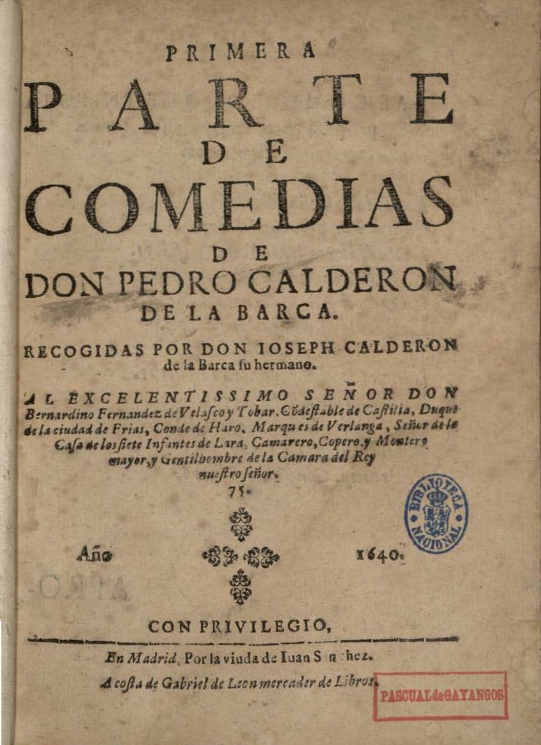

As such, the reasons to accept that the Portuguese anthology Doze comedias of 1647 is truly the source for the Brussels adaptation of La vida es sueño have become thinner. There is, however, a good alternative—more straightforward—source that I want to consider here: the 1640 reprint of Calderón’s Primera parte de comedias (1636), printed in Madrid by Maria de Quiñones.

Calderón’s Primera Parte

The 1640 reprint of the Primera parte was transported to the Habsburg Netherlands sometime before 1665, since the provenance of a convoluted copy of the reprints of Calderón’s Primera parte and Segunda parte (1641), now held by the Royal Library of Brussels, states that the convolute belonged to Karel van den Bosch, who was bishop of Bruges between 1650–1660 and of Ghent between 1660–1665. The provenance is in Latin and reads: “Soc Jesu Brug dd. Illmus Carolus vanden Bosch Ep. gand 1665”.

Calderón’s 1640/1641 convoluted anthology also contains seven plays that were translated in Dutch. The Primera parte includes:

- La vida es sueño (1635); translated and adapted by Schouwenbergh in Brussels as Het leven is maer droom (1647); reprinted in Amsterdam as Sigismundus, prinçe van Poolen (1654);

- La gran Cenobia (1625); translated and adapted by De Grieck in Brussels as Cenobia, Met de Doodt van Kaizer Aureliaen (1667);

- La devoción de la cruz (1636); translated and adapted by Antonio Francisco Wouthers in Antwerp/Brussels as De devotie van Eusebius tot het H. kruys (1665);

- Lances de amor y fortuna (1636); translated and adapted by Wouthers in Antwerp/Brussels as Strijd van de Min en het Geluk (c. 1665);

- La dama duende (1629); adapted by Andries Peys as De nacht-spookende joffer (1670) and another time by Lodewijk Meijer as Het spoockend weeuwtje (1670), both in Amsterdam.

In the Segunda parte, we can find:

- El mayor encanto, amor (1635); translated and adapted by De Grieck in Brussels as Ulysses in’t eylandt van Circe (1668) and another time translated by Jacob Baroces and adapted by Adriaen Bastiaensz de Leeuw in Amsterdam as De toveres Circe (1670)

- El galán fantasma (1637); translated by Simon Engelbrecht and adapted by David Lingelbach in Amsterdam as De spookende minnaar (1664).

Especially the Primera parte is interesting in this regard, since it contains four plays that were translated in Dutch in the literary circles of Brussels. With the exception of La vida es sueño, all plays were translated around or after 1665, which is the year that we know for certain that the copies of Calderón’s Primera and Segunda parte circulated in the Habsburg Netherlands.

A Litmus Test

One way to determine the right source—a litmus test if you will—is to compare the list of dramatis personae of La vida es sueño and its Dutch adaptation in four different sources: the Portuguese 1647 anthology of Doze Comedias, the Madrid 1640 reprint of the Primera parte, the Brussels print of Schouwenbergh’s adaptation of 1647, and the Amsterdam reprint of that same adaptation of 1654. In this comparison, we look for the order of the characters: are they listed according to when they first appear on stage or according to their respective social ranks? These were the two most commonly used ways to arrange the list of dramatis personae in seventeenth-century printed editions of plays. Compared to the Spanish prints, what did Schouwenbergh or the Dutch/Flemish printers choose?

| Personas que hablan en ella. | ||

| Rosaura dama. Segismundo Principe. Clotaldo viejo. Estrella Infanta. Soldados. | Clarin gracioso. Basilio Rey. Astolfo Principe. Guardas. Musicos. |

The Order in Primera parte […] (Madrid: Maria de Quiñones, 1640)

| Hablan en ella las personas siguientes. | ||

| Basilio Rey viejo. Astolfo. Rosaura. Clarin. | Cotaldo viejo. Segismundo. Estrella. Griados. |

The Order in Doze Comedias las mas grandiosas […] (Lisbon: Paulo Craesbeeck, 1647)

PERSONAGIEN BASILIUS, Koningh van Polen. |

The Order in Schouwenbergh’s Het leven is maer droom (Brussels: Jan Mommaert, 1647)

Perzoonagien van ’t Spel. Bazilius, Koning van Polen. |

The Order in Schouwenbergh’s Sigismundus, prinçe van Poolen (Amsterdam: Jacob Vinckel, 1654)

In the Spanish editions, two different ways are used to order the characters. In the official Madrid publication of La vida es sueño in the Primera parte, the list of dramatis personae is more or less ordered according to the principle of first appearance: Rosaura and Clarin feature in the first scene and they are later joined by Segismundo and even later by Clotaldo. The Lisbon version by Paulo Craesbeeck is arranged according to social rank with Basilio in the left row and on top as he is the King of Poland and thus the highest ranking character in La vida es sueño. The two Dutch prints seem to predominantly follow the Portuguese print in this principle. Is the Portuguese version of the text, then, the actual source? That is hard to say: the Dutch prints are actually also dissimilar from the Lisbon print in some specific ways as can be seen in the overview.

As such, the true source of La vida es sueño remains largely uncertain, although there are good reasons to accept either the Portuguese or Spanish print of Calderón’s famous play as the source text. The only option that remains to determine once and for all which text Schouwenbergh used for his translation is an external and internal collation of both prints. Only then, can we finally answer the question ‘Who has done it? Lisbon or Madrid?’.

Further Reading

Jautze, Kim, Leonor Álvarez Francés, and Frans R.E. Blom. ‘Spaans Theater in de Amsterdamse Schouwburg (1638–1672). Kwantitatieve en Kwalitatieve Analyse van de Creatieve Industrie van het Vertalen’. De Zeventiende Eeuw. Cultuur in de Nederlanden in Interdisciplinair Perspectief 32.1 (2016), 12–39.

Sullivan, Henry W. Calderón in the German Lands and the Low Countries. His Reception and Influence, 1654–1980. Cambridge Iberian and Latin American Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Vergeer, Tim. ‘Recasting a Comedia by Pedro Calderón de la Barca. Parallel Adaptations of El mayor encanto, amor in Brussels and Amsterdam, c. 1670’. Anuario Calderoniano 13 (2020), forthcoming.

© Tim Vergeer and Leiden Arts in Society Blog, 2020. Unauthorised use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Tim Vergeer and Leiden Arts in Society Blog with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

1 Comment

Interessant!